Arctic Report Card 2025: Rainfall, record warmth and rapid change

Higher air temperatures, record precipitation and accelerating environmental change continue to reshape the northern environment, according to the annual Arctic Report Card released on Tuesday by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

“To observe the Arctic is to take the pulse of the planet. The Arctic is warming several times faster than Earth as a whole, reshaping the northern landscapes, ecosystems, and livelihoods of Arctic peoples,” the report said.

“Also transforming are the roles the Arctic plays in the global climate, economic, and societal systems.”

Now in its 20th year, the peer-reviewed Arctic Report Card pulls together observations from across the circumpolar North, including Canada, to show how environmental changes are playing out across the region.

Record-high air temperatures across much of Arctic

Arctic surface air temperatures from October 2024 to September 2025 were the highest on record dating back to at least 1900. And the warmth wasn’t limited to a single season.

The Arctic experienced its warmest autumn on record, its second-warmest winter and its third-warmest summer.

Ice-retreat contributes to Hudson Bay summer heat extreme

Parts of Arctic Canada were among the regions that saw the most extreme warmth.

During autumn 2024, record seasonal temperatures were observed around Hudson Bay and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, where anomalies of 4–6 C above the long-term average were recorded.

“The extreme Hudson Bay temperatures during autumn 2024 were largely the result of record early sea ice retreat in eastern Hudson Bay that allowed for exceptional ocean heat uptake and supported a season-long marine heatwave,” the report said.

Although North Central Canada experienced below-average winter temperatures, winter warmth persisted in many other parts of the country’s High North.

“Most notably, Canadian Arctic Archipelago record-high temperatures persisted into winter, while the Lincoln Sea, adjacent central Arctic Ocean, and central and eastern Eurasia remained warmer than average,” the report said.

Wettest year on record, but summer dryness in parts of Canada

The Arctic saw its wettest year on record in 2024-2025, with unusually heavy precipitation spread across much of the year. Winter, spring and autumn all ranked among the five wettest since 1950.

However, parts of Canada were among the regions that bucked the broader wetting trend during summer.

“The summer dryness was especially apparent over large parts of Eurasia and northern Canada, likely contributing to the frequent Canadian forest fires,” the report said.

Wildfires are not a focus of the Report Card, but the authors note that summer 2025 marked the fourth straight year of above-average burned area across northern North America, with more than one million acres burned in both Alaska and the Northwest Territories.

The report also warns that as the Arctic’s water cycle intensifies, the combination of heavier precipitation in some seasons and drought in others is increasing risks for northern communities.

‘As the water cycle intensifies and extreme precipitation events become more common, disruption to ecosystems and human infrastructure will further impact Arctic communities,’ the report said.

Snow cover declines despite heavy winter snowpack

Snowpack across much of the Arctic was higher than normal at the height of the 2024–2025 winter and stayed that way through May. But that extra snow disappeared quickly, and by June much less remained on the ground.

Compared to the 1960s, the Arctic now has only about half as much snow on the landscape in June, a change that’s reshaping rivers, water supplies and ecosystems

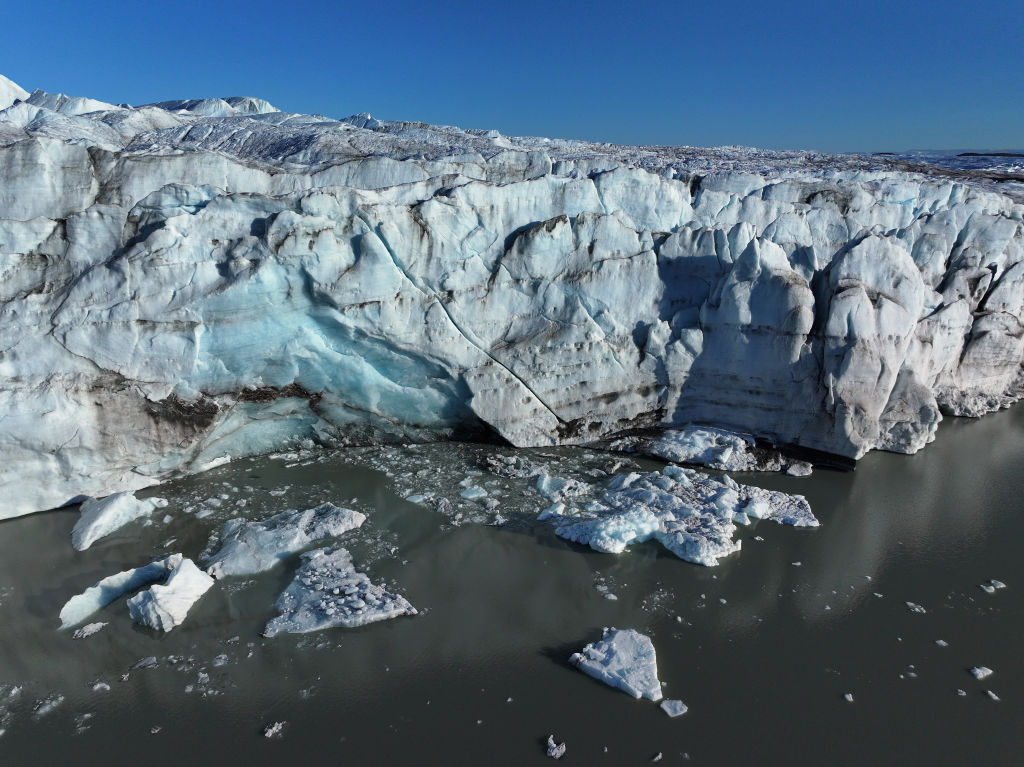

Sea ice loss continues

Sea ice shrank in 2025, continuing a long-term decline across the Arctic. Winter ice cover reached a record low in March, while summer ice levels remained among the lowest on record.

Today, most of the Arctic’s remaining multi-year ice is concentrated north of Greenland and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, making Canada’s High Arctic one of the last strongholds for the thickest, oldest sea ice.

Ice more than four years old has dropped by more than 95 per cent since the 1980s, something the report says has impacts beyond just climate.

“Changing sea ice extent and thickness is allowing increased marine traffic and prompting reevaluations of national security concerns,” the report said.

Greenland ice loss and Canadian glaciers contribute to sea-level rise

The Greenland Ice Sheet continued to lose mass in 2025, contributing to global sea-level rise, although losses were below the long-term average due to increased snowfall and reduced melt.

An estimated 129 billion tons of ice were lost during the year, below the annual average of 219 billion tons recorded between 2003 and 2024, but still part of a long-term downward trend.

Beyond Greenland, the report also highlights that glaciers and ice caps outside Greenland have rapidly thinned since the 1950s, adding steadily to global sea-level rise.

“All 25 of the monitored glaciers for which we have data (i.e., data was not available for 2 of the 27) recorded negative mass balances, consistent with the 2022/23 balance year,” the report said.

“This decline was most severe in Arctic Scandinavia and Svalbard, which experienced a precipitous drop in land ice since 2021.”

Warming oceans, changing ecosystems reach Canadian waters

Sea surface temperatures across much of the Arctic were among the warmest on record in 2025. The biggest jumps were seen in the Atlantic side of the Arctic Ocean, where August temperatures ran as much as 7 C above the 1991–2020 average.

On land, warming is showing up in rivers as well. The report documents more than 200 “rusting,” orange-coloured rivers in Alaska, where iron released from thawing permafrost is degrading water quality and habitat, with potential impacts on fish and subsistence resources.

Vegetation is changing too. Tundra greenness reached its third-highest level on record in 2025, continuing a long-term trend toward increased plant growth across the Arctic.

Arctic communities feel impacts firsthand

As Arctic residents are the first to feel the impacts of the changing northern climate, the report stresses the growing role of Indigenous-led monitoring and community-based observing programs, and emphasizes the importance of long-term staffing and training as northern communities respond to rapid change.

“After twenty years of continuous reporting, the Report Card stands as a chronicle of change and a caution for what the future will bring,” the report said.

“Transformations over the next twenty years will reshape Arctic environments and ecosystems, impact the wellbeing of Arctic residents, and influence the trajectory of the global climate system itself.”

Comments, tips or story ideas? Contact Eilís at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: New study links bacterial strain to muskox deaths in Canada’s High Arctic, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Flooding in Finland is getting worse, new climate report says, Yle News

Greenland: Facing rapid Arctic warming, Inuit call for full voice in COP30 climate decisions, Eye on the Arctic

Iceland: Iceland sees security risk, existential threat in Atlantic Ocean current’s possible collapse, Reuters

Norway: Weather above normal for 18 consecutive months, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: New NOAA report finds vast Siberian wildfires linked to Arctic warming, The Associated Press

Sweden: Proposal—Sweden’s 2030 climate targets to remain unchanged, Radio Sweden

United States: How the Arctic has been ‘pushed & triggered’ into climate extremes: paper, Eye on the Arctic