Analysis shows climate impacts will increasingly strain Canada’s Arctic defence infrastructure

Climate change is no longer a distant concern for Canada’s Arctic security. A new analysis from the research centre L’Observatoire de la politique et la sécurité de l’Arctique (OPSA) shows environmental change is already straining northern defence infrastructure across Inuit Nunangat.

“Climate change is reshaping the idea of security in the Arctic on a very practical level,” Magali Vullierme, the OPSA researcher who authored the analysis (in French only), told Eye on the Arctic. “Security isn’t just about military presence — it’s about logistics, infrastructure, and whether you can actually operate on the ground.”

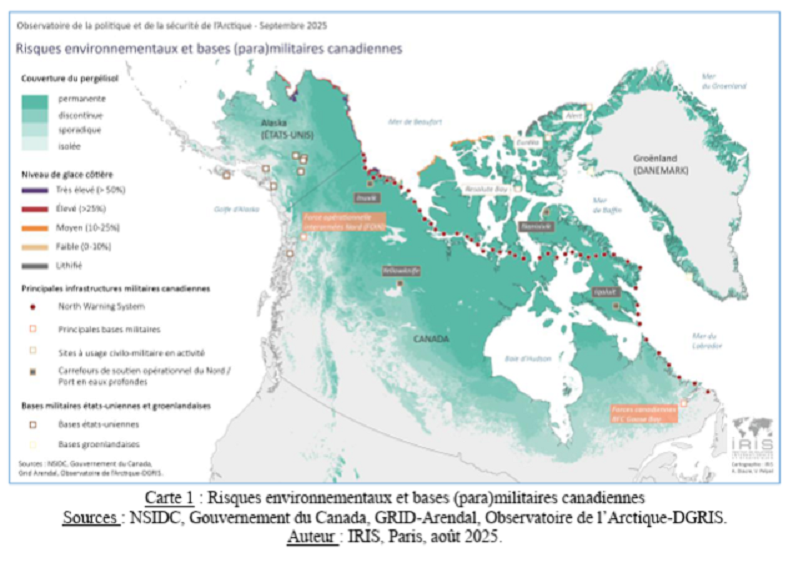

The analysis examines 56 military and paramilitary sites — including military bases, airports and North Warning System radar stations — by mapping their locations against data on permafrost thaw, coastal erosion and flood exposure. The approach highlights where climate-related risks intersect with Canada’s northern defence infrastructure.

“[The sites] that are most exposed are consistently in northwestern Canada,” Vullierme said. “That’s not accidental — the geological soils there contain much more permafrost, which makes infrastructure far more vulnerable as temperatures rise.”

The findings build on — but go beyond — a Department of National Defence (DND) evaluation of Arctic operations conducted between 2018 and 2022. That evaluation found that while immediate military threats in the Arctic remain low, the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) face mounting operational challenges linked to aging infrastructure, transportation limitations and environmental factors.

Yellowknife: A strategic hub

The analysis highlights Yellowknife—home to Joint Task Force North—as one of the vulnerable locations, facing projected flooding of just over one metre under a high-emissions scenario.

“It was concerning to see that the headquarters of Joint Task Force North in Yellowknife ranks very high in terms of risk,” Vullierme said. “This is infrastructure that really needs to be looked at, because Yellowknife and the surrounding region are on a high risk level of permafrost thaw.”

Any disruption to Yellowknife’s airport or military headquarters would be felt far beyond defence operations, the analysis continues, given the city’s more than 20,000 residents, and the many smaller communities that rely on it.

Airstrips: The biggest bottleneck

Despite billions of dollars promised in Canada’s updated defence policy, “Our North, Strong and Free”, the analysis warns that new investments will have limited impact unless basic transportation infrastructure is addressed first.

“If I had to choose one priority, it would be airstrips,” Vullierme said. “Airports are the only transportation infrastructure many Arctic communities have. They are essential for food supply, emergency response, and from a defence perspective, for deploying in the North.”

Currently, only 48 per cent of airstrips across Inuit Nunangat can accommodate the CAF’s Hercules aircraft, and only 13 per cent can handle the larger Globemaster. As permafrost thaw destabilizes runways, those numbers could shrink even further.

Why Remote Radar Sites Matter

The study also focuses on the North Warning System, Canada’s Arctic radar network operated jointly with the United States under NORAD. Many of the 47 Canadian radar stations sit on permafrost or along eroding coastlines, particularly in the North-West.

Some sites could face flooding of up to 2.3 metres.

Because of their remoteness, northerners are often the ones who monitor these sites and in general play a crucial role in sustaining Canada’s long-term defence posture, Vullierme said.

“Canada’s sovereignty in the North relies not only on radar systems, but on Inuit communities and the people that live there,” she said. “Canadian Rangers and Inuit communities are the ones checking these sites, maintaining presence, and asserting sovereignty every day.”

Inuit communities and security: “completely intertwined”

She stressed that even as radar technology modernizes and defence upgrades are rolled out, investment in Arctic communities will need to keep pace.

“When human security is taken seriously from a defence perspective, it can actually benefit northern communities,” Vullierme said. “It can mean more investment in housing, drinkable water, health services — the basics that communities have been asking for for decades.”

She also warned that neglect carries geopolitical risks.

“If the federal government does not invest in the North, there is a real risk that foreign states will,” she said. “In the Canadian Arctic, Inuit communities and security are completely intertwined — you cannot separate them.”

As climate impacts accelerate, integrating environmental realities into all aspects of Arctic defence planning — from infrastructure maintenance to emergency response and cooperation with Indigenous partners — will help strengthen the North against future challenges.

“The more you strengthen the human security of Inuit communities,” Vullierme said. “The more you will secure the Canadian Arctic in the long run.”

Comments, tips or story ideas? Contact Eilís at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: China, Russia pulling ahead of NATO in Arctic drone capabilities: report, Eye on the Arctic

Denmark: Danish intelligence report warns of US military threat under Trump, The Associated Press

Finland: Finland’s border fence almost ready in Lapland, Yle News

Iceland: NATO chief to Arctic Allies: “We’re all frontline states now,” as Iceland’s role grows, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: After three decades of Norway, Russia bridge-building comes a plan for detonation, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Kremlin says Russia is interested in foreign investment, including Arctic, after U.S. plans report, TASS reports, Reuters

Sweden: NATO sends more ships to High North “amid increasing operational demands”, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: Washington’s new envoy to Denmark pledges more US support for Greenland, Reuters