Introducing Canada’s ‘poop lady’

One of the first words in Inuktitut that Catherine Girard had to learn was the word for ‘poop’ – anak.

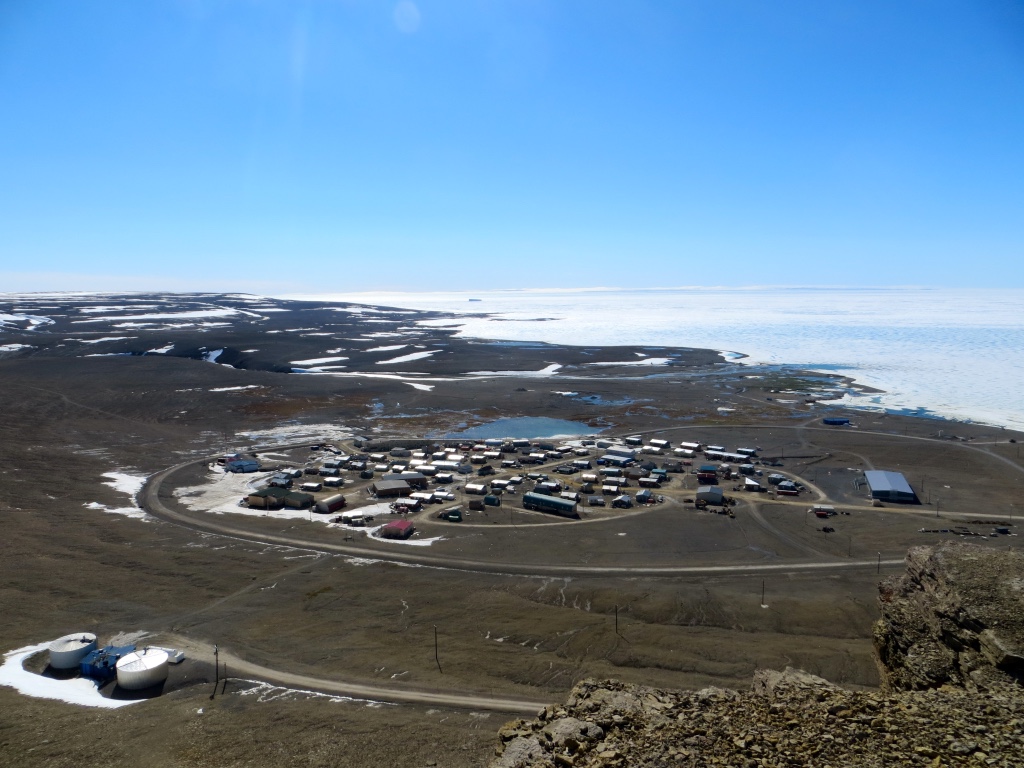

That’s because the 28-year-old PhD student at the Université de Montréal needed to collect stool samples from people in the tiny Arctic community of Resolute, in Nunavut.

Girard is doing research into the Inuit gut microbiome and how it may differ from that of other Canadians.

“To look at gut microbiome, which is the community of bacteria that lives in our guts, I have to collect stool samples and that has garnered me the nickname ‘the poop lady,’” said Girard.

Girard said she began going to Resolute, Canada’s second northernmost community, a few years ago to work on environmental research in the lakes surrounding the community of just over 200 people.

“When it became the time to choose a PhD project, I wanted to do something that is a little less abstract and maybe serves the community a bit better and was more interesting for the people who were welcoming me onto their land and into their town,” Girard said.

The microbiome plays a crucial role in human health. It helps us develop our immune system and process food that we eat and protects us against pathogens, Girard said. In recent years, a lot of research had been carried out to try and describe the microbiomes of different populations all around the world, she said.

“And we’ve been finding that different populations, especially those with traditional diets, have very singular microbiomes,” Girard said. “And no one had ever looked at Inuit gut microbiome.”

The Inuit have their own specific diet, often referred to as country food – food derived from hunting and fishing. It’s a diet that is rich in animal fat and proteins.

“I was interested in seeing how that specific diet would affect the gut microbiome,” Girard said.

Girard has collected samples from 19 people in the community.

“What we found is that when we compared these microbiomes to samples collected here in Montreal, we found that at a very broad level the community of microbiomes is very similar to what we see in Montreal,” Girard said.

That was a big surprise for the researchers who were expecting to see much more pronounced differences, she said.

“When we looked a bit deeper, we did see some subtle differences that we link back to the traditional Inuit diet,” Girard aid. There was an overrepresentation of bacteria associated with meat consumption. The researchers also found specific bacteria that were present only in the guts of the Inuit, but not in the guts of their Montreal participants, Girard said.

At the same time, in samples from Resolute researchers found fewer bacteria that are normally associated with fiber and citrus consumption, which are harder to get and a lot more expensive up north, Girard said.

But getting people to participate in her research was not an easy matter.

“When would get to the community, I would typically do a few announcements on the local radio, I would put up signs at the co-op and the post office, which are the hubs in the community the size of Resolute Bay,” Girard said. “Then I had a very patient field assistant, a local woman who would help me collect samples and recruit participants.”

Accompanied by her assistant, Girard would go door to door and try to explain her research. If the prospective volunteers spoke English, Girard would do the talking. However, if they were visiting an Inuktitut speaking household, the delicate task of explaining her research would fall on her assistant.

That’s when the word anak – Inuktitut for feces – came in very handy.

“It was a great icebreaker, it actually made things surprisingly easy to have a weird and humoristic sampling object,” Girard said. “People were pretty open-minded and said either ‘yes’ or ‘no’ very quickly. We always had a good laugh about it. That’s where the nickname ‘poop lady’ came from.”

Girard said the experience led to very close bonds with some of her study participants.

“It is a very intimate and personal, and can be an embarrassing sample to provide,” Girard said.

After she collects the stool sample, she does a quick interview for dietary habits, asking people about their eating habits and personal health, Girard said.

“So I do ask a lot of very personal and invasive questions,” she said. “And people have been so generous and patient with me and even people who weren’t interested in participating in the study ended up inviting me into their homes.”

Girard says she feels very privileged to have worked in the various parts of the Canadian Arctic and to have built a great relationship with a lot of people there.

“I think most Canadians don’t realize that we have a huge expanse of beautiful country up there,” Girard said. “And they don’t realize that there are people who live there, who are interested in what we do down south, interested in research.”

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Is climate change making the muskoxen sick on Victoria Island?, Eye on the Arctic

Denmark: Reinstilling pride in the Inuit seal hunt, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Indigenous rights under fire says Finnish Saami leader, Yle News

Greenland: The changing sea ice & what it means for Inuit, Eye on the Arctic

Iceland: Feature Interview – Hunting culture under stress in Arctic, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge can help us prevent climate changes says Ban Ki-moon, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Anthrax outbreak in Arctic Russia could be just the beginning: scientist, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Bear hunt quota worries reindeer herders in Sweden’s Arctic, Radio Sweden

United States: When Alaska fishing village residents can’t fish, normal life comes to an end, Alaska Dispatch News