Ottawa ready to discuss Inuit co-management of crucial Arctic habitat

The federal government is ready to sit down with Inuit leaders to discuss the creation of an Inuit-managed protected area in a crucial Arctic habitat located in the waters between Canada and Greenland, Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard Dominic LeBlanc said Monday.

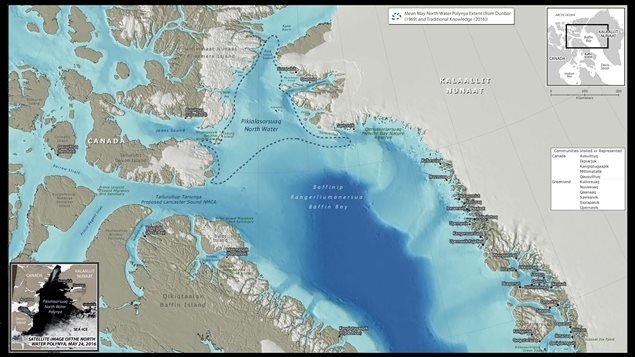

LeBlanc was reacting to a series of recommendations made last week by the Inuit Circumpolar Council’s Pikialasorsuaq Commission to create a new marine protected area in the North Water Polynya, known as Pikialasorsuaq in Inuktitut, designated and co-managed by the Inuit of Canada and Greenland.

The North Water Polynya is an area of year-around open water surrounded by sea ice between Canada’s Ellesmere Island and the northwestern coast of Greenland.

It is one of the most biologically productive areas in the circumpolar Arctic and is a breeding ground and migration area for animals such as narwhal, beluga, walrus, bowhead whales and migratory birds.

It is also of tremendous cultural and economic importance for the Inuit who have depended on its bounty for their survival for millennia.

Open to dialogue

LeBlanc said Canada values its relationship with Greenland and the Liberal government would look to support the commission’s Inuit-driven process “in the best way possible.”

“We acknowledge the 2017 report from the Pikialasorsuaq Commission on the North Water Polynya and look forward to discussing it with Inuit leaders,” LeBlanc told Radio Canada International in an emailed statement.

“Our government is supportive of Indigenous leadership and collaboration on marine conservation initiatives, including protected areas.”

Collaboration with Indigenous communities on marine conservation initiatives has been a fundamental aspect of the two existing Arctic marine protected areas: in the Western Arctic (Inuvialuit Settlement Region) as well as the recently announced Tallurutiup Imanga (Lancaster Sound) National Marine Conservation Area in the Eastern Arctic, LeBlanc said.

“We will look to this report and Inuit leadership to determine if and what mechanisms will be the best fit for partnership in future management of marine areas in the North,” he added.

Erasing borders between Inuit communities in Canada and Greenland

The Pikialasorsuaq Commission also wants Canada and Denmark to reinstate the free movement between historically connected Inuit communities on the Canadian and Greenlandic coastlines, said Okalik Eegeesiak, ICC chair and Pikialasorsuaq international commissioner.

Ever since governments in Ottawa and Copenhagen started playing more prominent roles in the lives of their Inuit citizens, their travel across the borders has become more and more restricted, especially because of security concerns following the 9/11 attacks in the United States, Eegeesiak said in a phone interview from Nunavut’s capital Iqaluit.

“We do not have passport offices in our small communities so these travel restrictions have impacted our family ties, it has impacted our cultural ties and we would like to see freer travel across the borders,” Eegeesiak said.

Listen to the interview with Okalik Eesegiak:

Lifting or easing these restrictions could be seen as part of the reconciliation efforts by Ottawa leading to Inuit self-determination, she said.

“We hope that the Canadian government will offer to take the lead in promoting the relationship and partnership with our communities,” Eegeesiak said.

There has been less and less direct contact between the coastal communities of Nunavut and Greenland because the Inuit respect the laws and regulations restricting travel, she said.

Long way to Greenland

There are no direct flights between Nunavut and Greenland, Eegeesiak said.

For example, an Inuk from the community of Grise Fjord on Ellesmere Island wishing to visit friends and family in Pituffik, Greenland, about 365 kilometres east across the Baffin Bay, would have to first fly 1,500 kilometres south to Iqaluit, then more than 2,000 kilometres south to either Ottawa or Montreal.

From there that person would need to catch a flight east across the Atlantic Ocean to either Copenhagen, Denmark, (5788km) or Reykjavik, Iceland, (3760km), only to take another flight back across the ocean to Nuuk, Greenland (1436km from Reykjavik or 3537km from Copenhagen). From Nuuk that’s another 1,503km flight north to Pituffik, and then that same journey back to Grise Fjord.

“We’d like to re-establish family ties, we’d like to relearn from each other our cultural heritage and make a positive impact for the area in terms of monitoring and managing the area on behalf of our respective governments,” Eegeesiak said.

Hope of good news for ICC meeting in Alaska

The governments of Canada, Denmark, Greenland and Nunavut were informally briefed on the recommendations of the Pikialasorsuaq Commission and the commissioners hope that these governments will be open to negotiating with the commission in the near future, Eegeesiak said.

“One of the milestones in terms of timelines would be by the next ICC general assembly, which is in July 2018 in Utqiagvik, Alaska, where we could hopefully report some positive progress in the recommendations in working with governments and consulting with our communities,” Eegeesiak said.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Inuit in Canada and Greenland seek co-management of crucial Arctic habitat, Radio Canada International

Finland: Finnish air pollution shortens life, Yle News

Greenland: Study finds increase in litter on Arctic seafloor, Blog by Mia Bennett

Russia: Pollution in Arctic Russian city of Nikel increases – Will new technology turn the tides?, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Stockholm cleans up and passes air quality test, Radio Sweden

United States: NASA research flight around the world pauses in Anchorage, Alaska, Alaska Dispatch News