Blog – The automation of Arctic oil: Good for companies, hard for communities

Big Oil is often regarded as an industry of yesteryear, unwilling and slow to change with the times. In some ways, corporations like Shell and BP might as well be painted as fossils digging up fossil fuels. But yesterday, while reading a story in the Financial Times titled “Drillers turn to big data in the hunt for more, cheaper oil,” I was struck by how readily they have adopted new technologies that will ostensibly allow them to continue to drill oil and gas for decades into the future.

‘Hey Google’

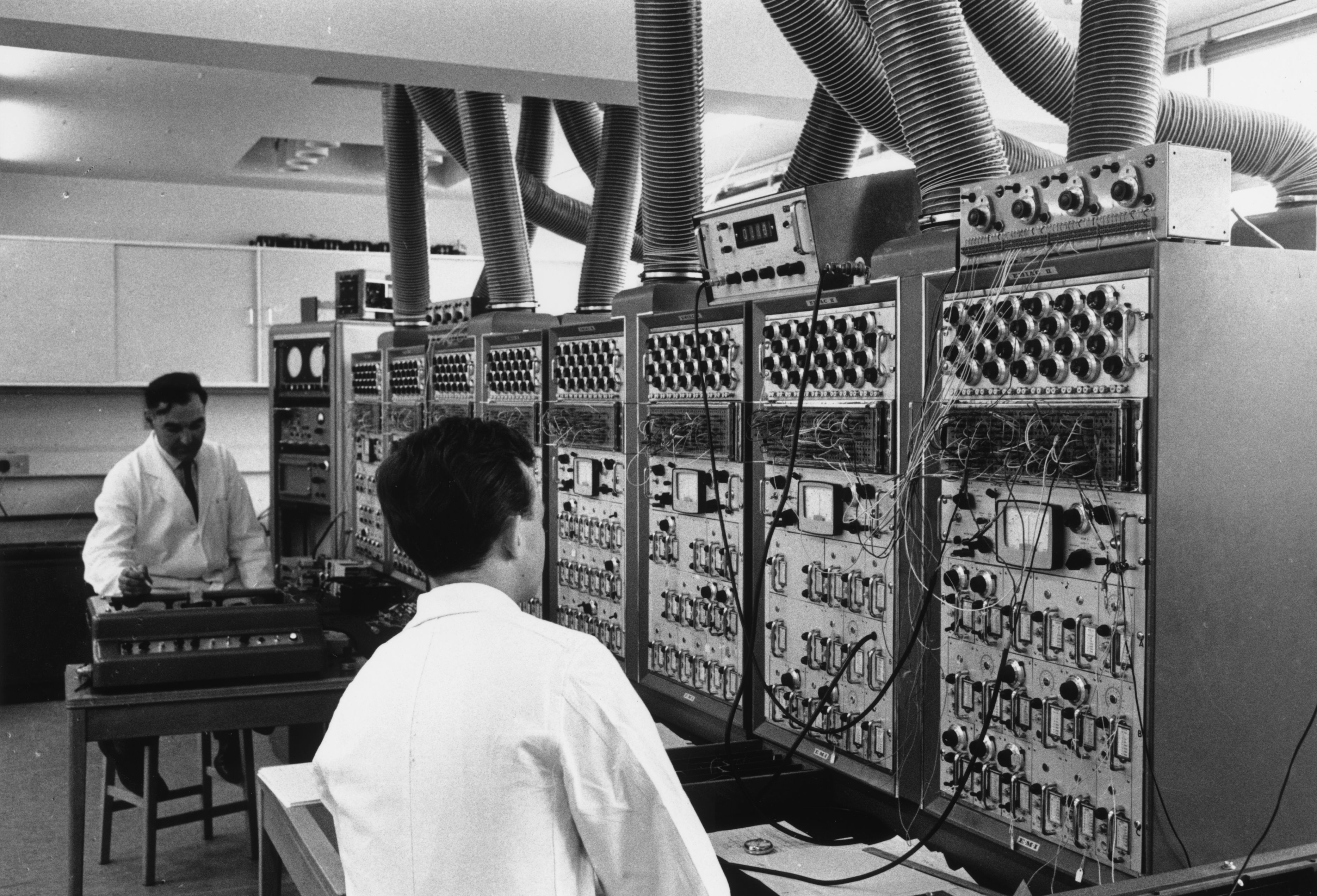

Companies like Schlumberger, the world’s largest oilfield services company, have offices in Silicon Valley, where they team up with neighbors like Google in order to learn how to apply machine learning algorithms on massive data sets. Schlumberger’s engineers are working with Google to use the internet company’s cloud computing powers to “achieve the next level of computing in oil and gas,” according to Ashok Belani, the company’s executive vice president of technology.

With machine learning, which allows computers to make insights from data without being specifically programmed, oil and gas companies can find new patterns in their massive data sets for applications like seismic analysis and production optimization.

Despite their lumbering appearance, oil companies have long been at the forefront of computing advances. And while they have also been gathering huge amounts of geological information since they first began prospecting, the difference now is that data storage is a lot cheaper, while machine learning algorithms can help make sense of big data. The Financial Times notes that Chevron’s volume of data has been doubling every 12-18 months. The expansion of the company’s Tengiz oil field in the Caspian Sea will involve the use of one million sensors.

The drop in energy prices and pressure to cut costs has also incentivized companies to adopt new, money-saving technologies like automation. Craig Clark, vice president of finance at Houston-based National Oilwell Varco, expressed in an interview with Forbes, “In a peculiar way this downturn has increased the interests of rig contractors and service companies as they look for ways to trim costs.”

Realizing that oil will not reach heights of $80-100 a barrel anytime in the near future, the industry’s goal is now to make oil profitable at $50-60 a barrel. With Arctic oil generally seen as profitable at a price of $90 a barrel, if technologies can advance such that production costs lower significantly even if the price of oil doesn’t go back up, then Arctic oil may be profitable at lower costs, too.

Matt Rogers, a consultant at McKinsey, stated to the Financial Times, “I don’t think we’ve built into our supply-side models just how much more oil this will provide… The world in 10 years will feel very different… It’s going to feel like we’re in Star Wars compared to where we are now.”

Automating oil production in the Arctic

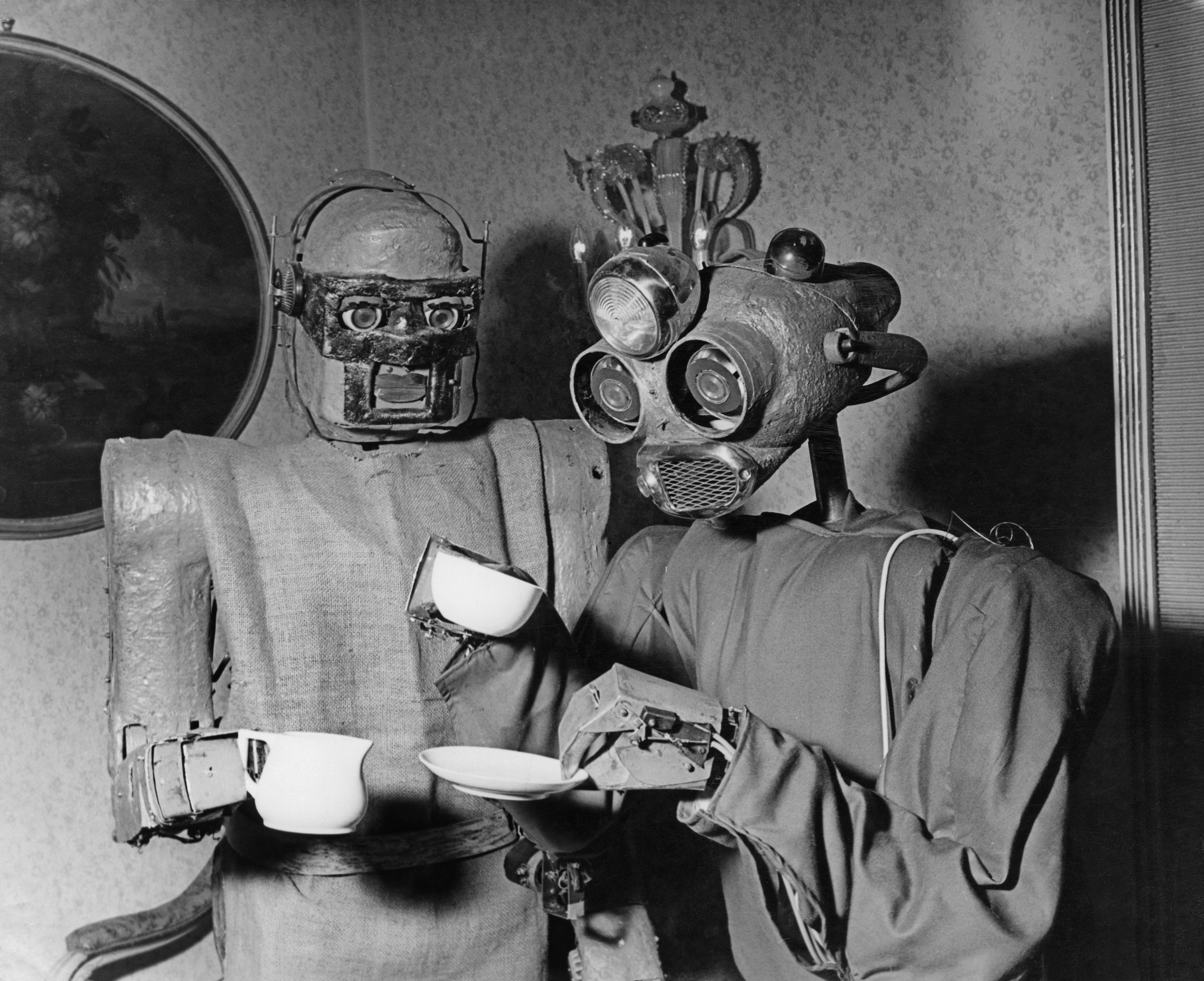

If Star Wars is the future of oil and gas, then Planet Hoth, with its gigantic robots walking mechanically walking across the snow, lies on the horizon for the Arctic oil frontier. But even AT-ATs had room for at least 40 stormtroopers inside. Years from now, drill rigs might not have any people at all. Mitch Pryor, co-founder of the Drilling and Rig Automation Group at UT Austin, remarked to Offshore Technology, “The companies are now saying the data we are getting from our sensors is something we can trust and use to make decisions possibly without a driller in the loop.”

Automation, which is reducing the need for human labor across numerous industries, is thus starting to make headway in the oil and gas industry. Just as Amazon rolled out its cashier-less grocery store in Seattle a few weeks ago, rigs may soon require only a fifth of their current crew sizes. The Financial Times article notes that Belani, the tech VP at Schlumberger, believes that shale drilling rigs that have 26 people today might only have five people in five years’ time.

The invention of automated drilling even has its roots in the Arctic. In 2006, NASA tested a Mars prototype drill on Devon Island in Nunavut, Canada, marking supposedly the first time that automation completely controlled a drill rig. While NASA’s Mars drill would look for water and life on the Red Planet, the same technologies will allow industry to scour harsh environments without risk to human life. There are other overlaps between NASA’s inventions and Arctic oil and gas, too. U.S. company Energid Technologies developed software for NASA to control lunar rovers that oil companies are now using to program robots to lay out a confined rig floor on the seabed.

The Arctic is fast becoming an automation frontier in the oil and gas industry. In 2011, the Society of Petroleum Engineers published a newsletter that argued, “Statoil needs a rig capable of drilling in the Arctic, and other environments that would put workers out of harm’s way.” Last summer – six years later – Statoil was employing “the most advanced automated drilling control (ADC) system ever installed on a rig, and the first ADC system on a floating rig” on its Songa Enabler offshore drilling rig in the Koigen Central wildcat well in the Barents Sea. While the well, which proved dry, was plugged and abandoned, the attempt at least marked an advance for Statoil in using ADC technology to explore for Arctic oil.

The rise of new technologies like autonomous vehicles can make monitoring of onshore and offshore pipelines easier, too. This could make Arctic drilling safer for both the environment, thanks to added monitoring, and for humans, who may no longer have to brave bad conditions to carry out checks.

Automated robots could soon be probing for leaks despite stormy seas that might keep humans onshore, for instance, while automated drill pipe handling reduces human risks by obviating the need to have people manning the drill floor. More dramatically, over time, the introduction of automated technologies may mean the rise of fully automated drilling operations, according to a report from DNV GL, a risk management company based in Norway.

The human consequences of automation

While it is all well and good that risks to human life will be lowered thanks to automation, Arctic communities that depend on the oil and gas industry for employment may not see many new job opportunities if and when fully automated rigs start appearing offshore.

In Norway, Petro Arctic, a network of Norwegian companies serving the country’s northern oil industry, predicted late last year that 3,000 jobs would be forthcoming over the next ten years thanks to the industry’s northern expansion. But given the seriousness with which oil majors like Statoil and Chevron are pursuing automation, communities should be wary of any promises of jobs from new oil and gas development.

Furthermore, the fewer people working on rigs, the fewer additional services, like hotels, catering, and flights, will be needed. A report by the pro-industry Alliance for Innovation and Infrastructure explained that in Alaska in 2013, jobs in oil and gas development and related services provided a third of all wage and salary employment. That translated into some 111,000 jobs and over $6.5 billion in wages If automation brings the cutbacks and cost-savings that oil companies are hoping for, a lot of people in places like Alaska and Norway will be hurting.

The rise of fly-in, fly-out labor thanks to cheap aviation has already curbed the benefits northern settlements are able to realize from industries like mining. If Arctic oil drilling results in not having to fly in or out any labor whatsoever, the scales may tip even more in favor of oil companies as opposed to Arctic communities.

Finally, as the hydrocarbon sector goes the way of high tech, employees will be expected to have even more advanced skills. In the near future, offshore oil platforms may require software engineers rather than rig operators. Many Arctic communities, already suffering from a major education deficit with the south, might not be able to train their residents for this type of work. That is why as robots rather than people begin exploiting hard-to-reach resources, it is becoming increasingly important that education rather than extraction comes first in Arctic development.

This post first appeared on Cryopolitics, an Arctic News and Analysis blog.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Arctic nickel, not oil, could soon power the world’s cars, Blog by Mia Bennett, Cryopolitics

Germany: Cheap oil from the Arctic? Fake news, says climate economist Kemfert, blog by Irene Quaile, Deutsche Welle

Norway: Dwindling interest in Norway’s Arctic oil raises many questions, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: For Vladimir Putin, Russia’s prosperity will come from the Arctic, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: EU gives financial push to battery factory in Northern Sweden, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: Big questions emerge over $43 billion gas-export deal between Alaska and China, Alaska

Thanks for the post, nice information about the automation of arctic oil good for companies… it is really helpful.