How do insects survive the winter? Not the way we thought

A new study is revealing the science behind how some insects survive winters in harsh climates, and it goes against previously-believed theories.

Published by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, the article examines how antifreeze proteins found in some insects prevent ice from forming and spreading inside their bodies.

One of the authors, Valeria Molinero, a professor of chemistry with the University of Utah, said while it’s long been known that insects have these proteins, little is understood about the way they bind to ice.

Previous research led some scientists to believe that the antifreeze proteins reorder water molecules inside an insect’s cells into an ice-like structure, which would allow the protein to stop the formation of ice.

“Essentially they decided if you have a protein that already forms [an] ice-like order at the surface, then this [ice-like structure] meets ice and they just bind together like a sandwich,” she said.

This would trap the ice and stop it from forming inside the insect.

But, using a molecular simulation with the antifreeze protein found in the mealworm beetle, the researchers from the University of Utah and University of California, San Diego found the protein just needed to be parallel to an ice crystal to stop it from spreading. In other words, it does not create an ice-like structure to stop the formation of ice.

Application in molecular design

Molinero said this new finding could be beneficial for a growing area of research in designing new molecules that mimic this antifreeze mechanism.

She said there’s interest in using them for things like organ preservation, de-icing planes, and even preventing frozen foods from getting frostbite.

“When you have commercial ice cream, you need to prevent the ice cream from developing very large crystals because … it’s not nice to have ice cream with large crystals, at least in my opinion,” she said. “It’s less important but it’s delicious.”

Molinero said more research is needed to better understand exactly how these molecules work and how to mimic their effects.

In southern and Arctic insects

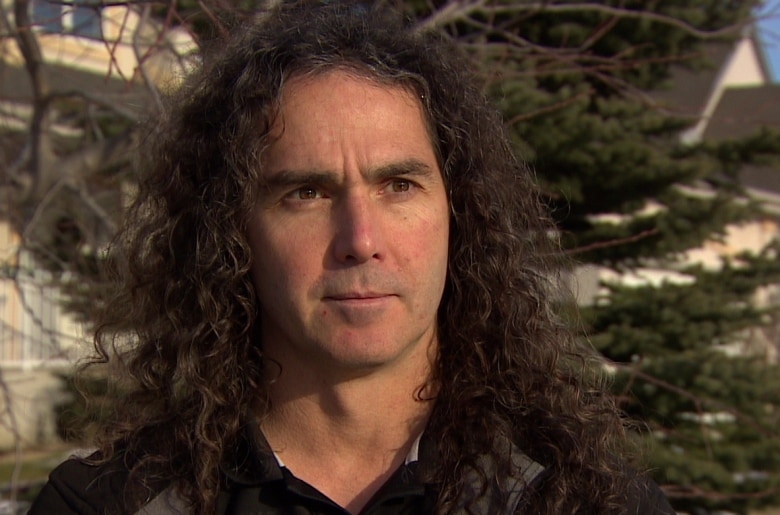

Entomologist Taz Stuart is familiar with insects that have these proteins. He said they can be found in any adult insects that overwinter in harsh climates and explained that when the temperature dips below freezing, they go into dormancy.

“Insects are very intelligent,” he said. “It’s a unique science for them to survive overwintering.”

To overwinter, insects go into a state called diapause.

“Literally it’s like a bear going to sleep for the winter. [Insects] will wake up if it gets warmer,” said Stuart.

“You know you have one day that’s minus 40 and then a couple days later could be plus 10 and they’ll go, ‘Hey wait a minute is it time?’ They’ll look at the sun and go, ‘Oh oh nope it’s not, the sun’s too low in the sky, we’ll wait another you know a month or two.'”

In the Arctic, these antifreeze proteins have been found in species of spiders, beetles and stinkbugs.

Stuart said there is at least one species of mosquito in the Canada’s Northwest Territories — Culex tarsalis — that has this antifreeze protein. The species was newly discovered in the territory, but it’s commonly found in southern Canada.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Which marine mammal is most vulnerable to Arctic vessels?, CBC News

Finland: Climate change brings new butterfly species to Finland, Yle News

Norway: Northern Barents Sea warming at alarming speed, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: Arctic and Antarctic waters breed more new species than tropics: study, CBC News