Climate change is driving micro-algae blooms into High Arctic and may affect food chains, says study

Micro-algae blooms at the base of marine food chains are heading north at a rate of one degree of latitude per decade as the climate warms, according to a new study released on Monday.

The study, Northward Expansion and Intensification of Phytoplankton Growth During the Early Ice‐Free Season in Arctic, appeared in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

The study was based on satellite images of ocean colour taken between 2003 and 2013.

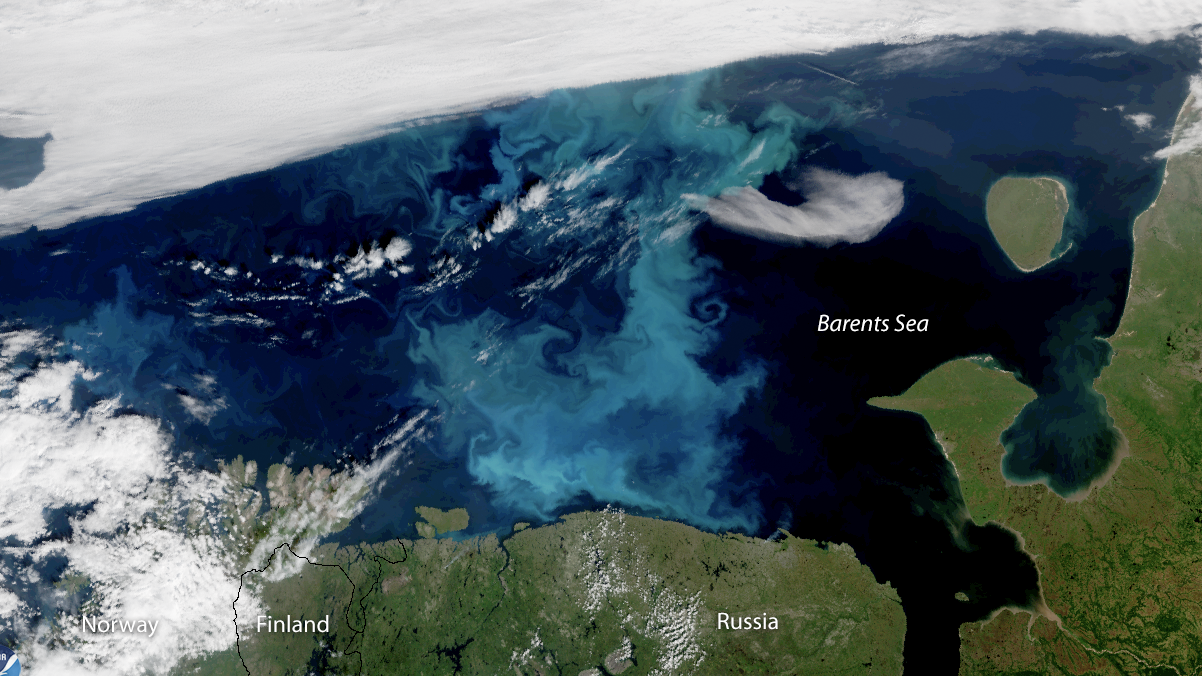

The images show the micro-algae blooms, phytoplankton spring blooms, were present in the Arctic Ocean, either earlier than usual or in places they were previously non-existent.

“The phytoplankton spring bloom, which can contribute to more than half of the annual primary production in open waters in some regions of the Arctic Ocean and which is tightly linked to the ice cover, is undergoing drastic changes,” the authors said in their summary.

‘Drastic consequences for ecosystem’

“We don’t know yet how the presence of the blooms are going to evolve,” Sophie Renaut, a Ph.D. student at Laval University in Quebec City, Canada, and lead author of the study, told Eye on the Arctic in a phone interview on Monday.

“But (the blooms) are appearing earlier than usual or in places where they haven’t been before. And we don’t know yet how their presence will match, or mis-match, with micro-organisms that are also there at these times, or who have not encountered the blooms before. But the effects on the food web could be drastic.”

Phytoplankton are micro-algae found in water that convert sunlight into chemical energy.

Typically, they bloom in the Arctic in spring, but have not produced at higher latitudes covered by sea ice. But now this is changing, as sea ice declines, breaks ups up earlier, or doesn’t form at all, say the researchers.

Norwegian, Russian Arctic areas most affected

The two areas the study found most affected were the Barents Sea north of Norway and Russia’s western Arctic; and the Kara Sea, located just east of the Barents Sea and north of Siberia.

Renaut says more research is now needed to better understand how the phytoplankton blooms have evolved since 2013.

“We see the Arctic is changing very fast, and faster than the other regions of the world,” she said. “What we don’t know is how these changes are going to effect the interplay with different organisms. This was a short period of 10 years that we studied and the next step is to monitor what has happened since.

“There’s more we need to understand.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story included one paragraph where phytoplankton was described as a bacteria. While some phytoplankton are bacteria, in this case, it should have been described as “micro-algae” as referred to elsehwere in the text. This version has been corrected.

Write to Eilís Quinn at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Thawing permafrost in Canada’s Northwest Territories releasing acid that’s breaking down minerals: study, CBC News

Finland: Increasing ocean acidification ushering era of uncertainty for Arctic, says report, Eye on the Arctic

Greenland: Glacier half the size of Manhattan breaks off Greenland, CBC News

Iceland: Scientists puzzled by right whale’s appearance off Iceland, CBC News

Norway: Thawing permafrost melts ground under homes and around Global Seed Vault in Svalbard, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Arctic coastal town of Dikson is fastest-warming place in Russia, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Warm temperatures lasting into autumn across Sweden, Radio Sweden

United States: New study predicts ‘radical re-shaping’ of Arctic landscape by 2100, CBC News