Alaska reckons with missing data on murdered Indigenous women

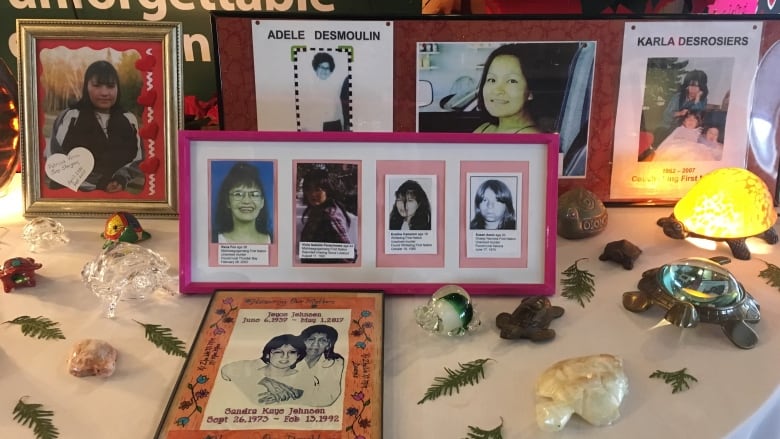

Indigenous women and girls are murdered or disappear from American cities in alarming numbers. But no one knows the true scope of the problem, because no one regularly reports the data. A new effort aims to spotlight both problems — the homicides of Native women, and the lack of data about their deaths and disappearances.

At the U.S. Capitol, Sen. Lisa Murkowski (Republican representing Alaska) wore purple Wednesday, because she said that was the favorite color of Ashley Johnson-Barr.

“Ashley was 10 years old when she was brutally, brutally murdered in Kotzebue [northwest Alaska], after being kidnapped,” Murkowski said at a press conference about missing and murdered indigenous women.

Murkowski also spoke about Sophie Sergei, a student at the University of Alaska Fairbanks who was raped and murdered in a dormitory bathroom.

“That has been a cold case now for some 25 years,” Murkowski said.

Such stories never leave her, she said. But they do often drop out of the public record, or never make it into the record in the first place.

Murkowski and Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (Democrat from North Dakota) have sponsored a bill to improve federal data on Native American homicide victims and missing people. Heitkamp said information is the first step.

“You will never solve a problem you won’t admit you have, that you don’t have data on, that you don’t have the ability to actually analyze,” said Heitkamp, who is in her final weeks in the Senate, having lost her re-election bid last week.

A complex search

The Urban Indian Health Institute highlights the lack of data in a new report. The institute, part of the Seattle Indian Health Board, contacted police departments in 71 cities, Orlando (Florida) to Utqiaġvik (northern Alaska), and asked for case information on all missing and murdered indigenous women going back to 1900. The report says 31 police departments, including the Alaska State Troopers, provided no data at all, or didn’t respond by the report deadline. (An AST spokeswoman said the agency provided data from recent years on Oct. 29.)

The researchers also combed social and traditional media, and reached out to community members. Ultimately, they found 506 cases in the 71 cities. They say it’s a data snapshot.

“First, I want to tell you, I had no federal funding for this. I financed most of it myself, through speaking fees I charge,” said Abigail Echo-Hawk, one of the report authors. She lives in Seattle now, but she’s originally from Fairbanks.

“I did this report for less than $20,000, when the Department of Justice, the FBI, states, cities told us they couldn’t do it. There wasn’t budget line-items. They didn’t have the resources.”

Anchorage police leading by example

The report singles out Anchorage police (southern Alaska) for excellence. The authors say the Anchorage Police Department saw the request for data as important, and got on it promptly. The department found 31 cases of missing or murdered Native women. And the hero of that statistical mission is Sgt. Slav Markiewicz of APD’s homicide unit.

“I try to maintain good databases,” he said.

Markiewicz has been devoted to those databases since he started in homicide in 2005, and he got help from detectives in culling back through the old files.

“All the way to the 70s and it was difficult and we were afraid that it might not be completed but we tried to gather, to get all those cases listed,” he said.

Markiewicz said when APD started the database there was resistance to collecting information on victim race. The police should be colorblind, the argument went, because all homicide victims are important.

“I still wanted to have that information included,” Markiewicz said,” because I knew that when you have that information you can adjust your strategies … not only in order to solve these crimes but hopefully prevent them.”

Markiewicz is retiring at the end of the year but said he’s confident his successor will keep up the devotion to good data collection.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Mining and energy projects near Indigenous communities undermine womens’ safety, experts tell Canada’s inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women, CBC News

Denmark: Nordics report high abuse levels against women, Radio Sweden

Sweden: Reports of violent crime increasing in Sweden’s North, Radio Sweden

United States: Violence against Indigenous women still a hot topic for Alaska Federation of Natives, Alaska Public Media

Did they consider Israel Keyes?

The whole question of missing and murdered Native women needs more context…the numbers of unreported or under-reported Native men and boys for instance. In growing up here in Montana three men I knew allegedly hanged themselves while in local jails…I say allegedly but one of them had electrical burns on his back and chest when examined by the San Francisco Coroner’s Office. Both of the others were known to be worried about being arrested, because “The cops don’t like me very much here” as he told me the night before he was picked up…and died.

WHO can I talk to about this? …and just how common are these ‘suicides’?

I bet that when figured for population sizes they are at least as frequent as young unarmed Black men gunned down in the streets…but where’s the public outcry?

as if the agents had not talked about them to me!