Radiation seeping out from 30-year-old nuclear-sub wreck in Norwegian Sea

One sample taken from an open ventilation hole of the wrecked Soviet nuclear-powered submarine shows levels of about 800 Becquerel per liter.

The joint Norwegian-Russian expedition on board research vessel G. O. Sars is starting to see results from radiation samples collected on and around the Russian Northern Fleet submarine that sank south of the Bear Island in the Norwegian Sea in 1989.

The highest level researchers found was around 800 Bq per litre. Typical levels for seawater in the Norwegian Sea today are around 0.001 Bq per litre. In other words; the samples shows radioactivity 800,000 times higher than normal, Norway’s Institute of Marine Research informs.

Another sample showed 100 Bq/l. Other samples from the same pipe hole showed normal levels, making the researchers believe radioactivity is pumped out in steams varying with the ocean currents at the site.

Not a surprise

Expedition leader Hilde Elise Heldal is not surprised to discover leakages of radioactivity from this pipe on the tower of the submarine wreck.

“We took water samples at this particular pipe because it was here the Russians documented leakages both in the 90s and last time in 2007,” Heldal says. She underlines that 100 Bq/l is not dangerous at all. “After the Chernobyl-accident in 1986, Norwegian authorities set an upper limit of 600 Bq per kilo.”

The 600 Bq/kg limit is for food consumption; fish or meat.

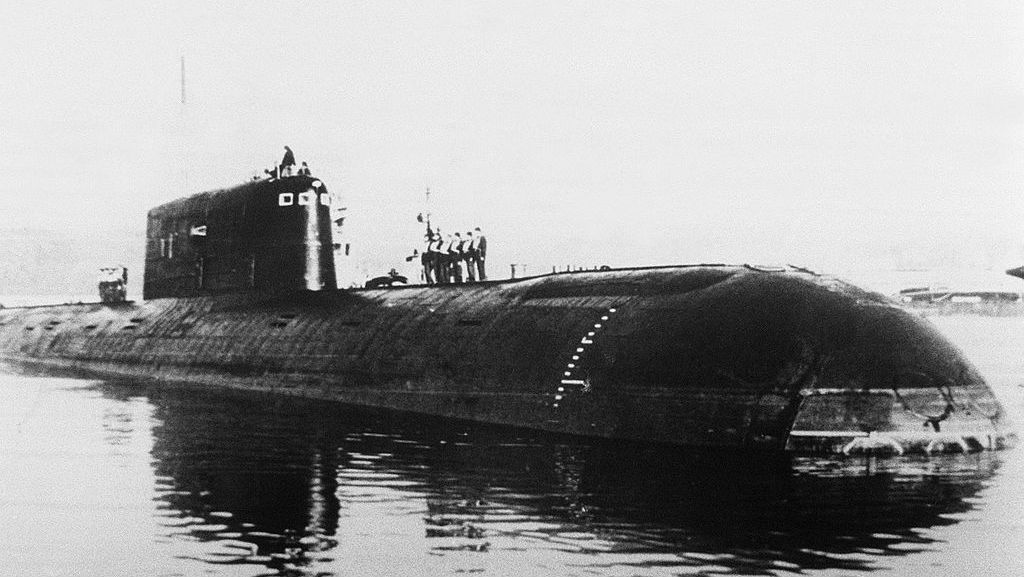

Komsomolets (K-278) rests at the seafloor at a depth of 1,680 meters, where there is very little marine life, so the risks of having the radioactivity into the food chain is very little.

Komsomolets has one 190-megawatt reactor and two torpedoes with plutonium warheads, each about 3 kg.

The leakages of radioactive Cesium-137 discovered is from the reactor.

“What we have measured has very little impact on Norwegian fish and seafood. Levels [of radioactivity] in the Norwegian Sea are in general very low, and the pollution from Komsomolets is quickly diluted to harmless levels because the wreck is at such deep water,” Hilde Elise Heldal says.

She maintains the importance of continued monitoring of the submarine wreck.

“Good documentation of the levels in both seawater, sediments, and not least in fish and seafood is needed. We will therefore continue checking both Komsomolets especially and Norwegian waters in general,” Heldal tells.

The Norwegian- and Barents Seas are the best fishing grounds in Europe and of big economic importance for both Russia and Norway.

The researchers will bring home water samples and sediments for more thorough examination.

Damaged hull

Photos and video taken by the remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV) show big damages to the hull in the front part of the submarine. This is where the two torpedoes with nuclear warheads are located.

With a half-life of 24,000 years, concerns are that the plutonium in the two warheads could corrode in a chemical process with the titanium hull of the submarine.

Frederic Hauge with the environmental group Bellona was in the early 1990s working in close cooperation with the Dutch-Russian Komsomolets Foundation, a team set to examine possibilities of lifting the wreck from the seafloor. The Foundation consisted of the Rubin institute in St. Petersburg that once designed the submarine and a salvaging consortium from the Netherlands.

“At the time we concluded it would be technically impossible to lift the submarine. The weight of 1,700 meters [about 6,000 feets] of wires would simply be too heavy,” Hauge tells.

Today, Frederic Hauge argues there are other wrecks more urgent to life than Komsomolets.

“Komsomolets is at so deep waters that there are little chances of seeing dangerous levels of radiation coming into the food chain. I’m much more concerned about the K-159, on more shallow waters in the important fishing grounds just north of the Kola Bay in the Barents Sea,” Frederic Hauge says.

With two nuclear reactors, the November-class K-159 sank during stormy weather in August 2003 while being towed from Gremikha naval base towards the Nerpa shipyard where the submarine was to be scrapped.

The nuclear fuel in the two reactors is of uranium oxide type with an aluminium matrix and stainless steel as cladding. With an enrichment of about 20%, the total load of uranium-235 is 50 to 60 kilograms.

“The sunken Russian nuclear submarine K-159 is of great concern,” a 2017 report concluded based on a collaborative effort between the Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority and the Russian Energy Safety Analysis Centre of IBRAE RAN.

Other nuclear-powered submarines on the Arctic seafloor are found in the Kara Sea east of Novaya Zemlya, used by the Russian navy to dump damaged reactors during the Cold War.

Related stories from around the North:

Norway: Was a nuclear-able Soviet sub near Norway’s coasts during a deadly 1984 fire?, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Russian secret sub to be repaired and put back in service, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: U.S. Navy plans to be more active in the Arctic, Alaska Public Media

No increase in radiation is “safe.” Every additional amount increases cancer and mutation already caused by natural background radiation. Governments are making arbitrary decisions on how much of an increase in disease they are willing to tolerate and calling anything below that arbitrary number “safe.”