Quebec should apologize for systemic discrimination in treatment of Indigenous people, Viens report says

The Quebec government should apologize to First Nations and Inuit for the harm they have endured as a result of provincial laws, policies and practices, says the author of a damning report into the treatment of Indigenous people.

The recommendation is the first of 142 calls to action laid out in retired Superior Court justice Jacques Viens’s 520-page report released Monday.

“The unequal relations that have been established have deprived Indigenous peoples of the means to allow them to fulfil their own destiny and have, in the process, given a certain mistrust of public services,” Viens said Monday in Val-d’Or, the northern mining community where it was released.

In the report, Viens said it is “impossible to deny” Indigenous people in Quebec are victims of “systemic discrimination” in accessing public services.

He said improvements are needed across the spectrum, including in policing, social services, corrections, justice, youth protection and mental-health services, as well as to the school curriculum to properly reflect the history of First Nations and Inuit in the province.

He also recommended the province’s ombudsman be put in charge of ensuring the calls to action are implemented.

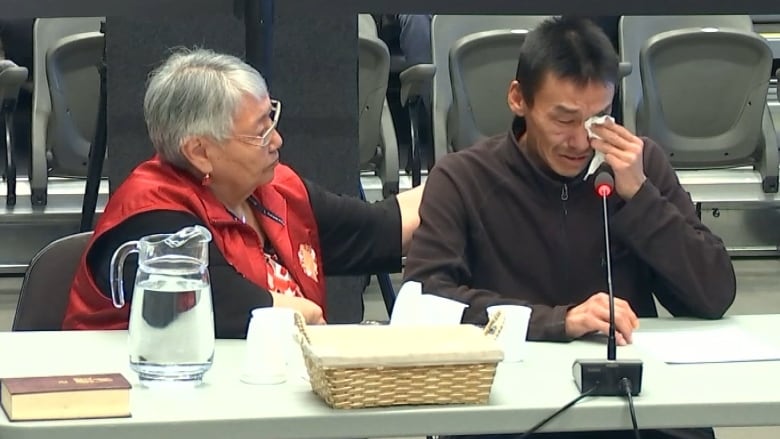

The report is the result of more than nine months of testimony about the decades of abuse, mistreatment and neglect endured by Indigenous people.

The inquiry was launched in December 2016 by the former Liberal government, under pressure to act in the wake of a Radio-Canada investigation into allegations of police misconduct against Indigenous women in Val-d’Or, a city 500 kilometres northwest of Montreal.

Viens was given a broad mandate: To look into the treatment of First Nations and Inuit people in Quebec by the public service. The commission wrapped up its hearings last December.

A total of 1,188 stories and expert opinions were shared over 38 weeks of hearings.

Although the hearings were held mainly in Val-d’Or, the commission also travelled to Mani-Utenam, Mistissini and Montreal, as well as Kuujjuaq and Kuujjuarrapik in northern Quebec.

In all, 277 citizens came forward with personal stories of having dealt with police, hospital staff and other public services, including representatives of the province’s youth protection agencies and the justice system.

Premier acknowledges need for change

Quebec Premier François Legault said Monday he would look closely at the report and its recommendations. He said it’s clear previous provincial governments must bear responsibility for the poor treatment of First Nations people and Inuit.

“There are many worrisome things in the report and we need to change the way we provide services to Indigenous people in Quebec,” Legault said on Radio-Canada’s Tout un matin.

Legault is set to meet with Indigenous leaders later this week and address the National Assembly about the report.

Public Security Minister Geneviève Guilbault and Lionel Carmant, minister responsible for the province’s youth protection services, were in Val-d’Or for the report’s release.

‘Commissions come and go’

In a statement, the advocacy group Quebec Native Women expressed concern the inquiry’s broad mandate had shifted the focus away from those who came forward with allegations against Quebec police.

“We welcome this work and hope that finally these findings of failure will find appropriate remedies,” the statement said.

“On the other hand, it would be wrong to believe that the commission has duly fulfilled its mandate with Indigenous women.”

Ghislain Picard, regional chief of the Assembly of First Nations for Quebec and Labrador, had similar concerns prior to the report’s release.

He said he is not expecting the findings to include what he really wants: accountability from police about their treatment of Indigenous women.

Picard, who appeared four times before the commission, said it will be important to make sure whatever recommendations are made in the report are acted upon.

“Too many times in the past, we’ve seen commissions come and go, recommendations come and go, with very little action.”

With files from Catou MacKinnon

Note: This story has been updated following the release of the report.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Death in the Arctic: A community grieves, a father fights for change, Eye on the Arctic special report

Finland: Police in Arctic Finland overstretched, says retiring officer, Yle News

United States: Alaska reckons with missing data on murdered Indigenous women, Alaska Public Media