Arctic sea ice loss linked to spread of deadly virus in marine mammals

The reduction of sea ice in the Arctic is destroying animal habitat and affecting the entire planet. It is also spreading an invisible threat that kills marine mammals in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, as a recent study shows.

The paper published in Scientific Reports found that Phocine distemper virus (PDV) had spread from North Atlantic seals to populations of sea otters living in the North Pacific Ocean.

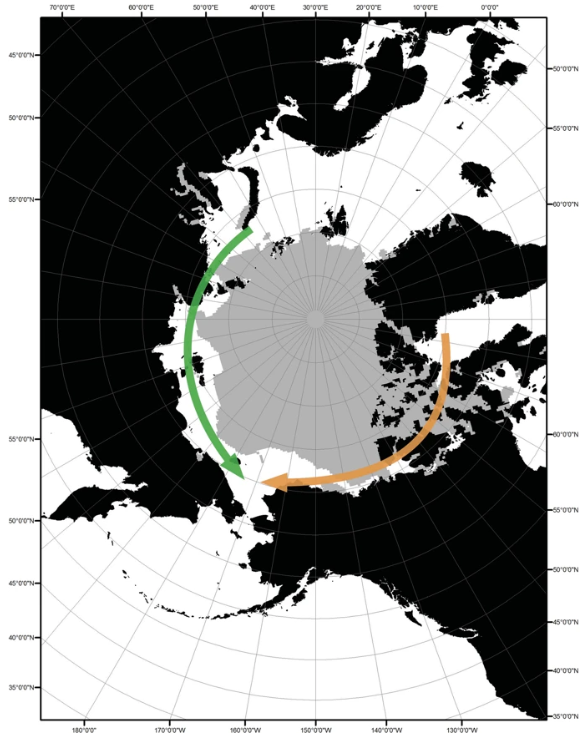

Their findings suggest that the virus travelled from one ocean to the other thanks to the reduction of Arctic sea ice.

Eye on the Arctic spoke to author Dr. Tracey Goldstein from the University of California, Davis, and asked her a few questions about her study:

The 15-year study began in 2004 when Alaskan sea otters were found dead from the virus.

“That was really surprising to us because sea otters don’t range widely,” said Dr. Tracey Goldstein.

The team also recalled a really large outbreak of the PDV among North Atlantic seal back in 2002 with its peak in August-September. September is also the period when the sea ice is at its lowest.

Taking those facts into consideration, the researchers tried to see if a link existed between the low sea ice and the spread of the virus.

Arctic species could be a reservoir of the virus

At the time, they thought the virus could have been spread by grey seals, a species that acts as a bridge between Arctic species and North Atlantic seals. Grey seals can get infected by the virus but usually don’t get seriously ill or die from it.

So the idea was that grey seals potentially brought the virus down from the Arctic to the North Atlantic species, causing the outbreak in 2002.

Other work had also suspected that Arctic species could be the reservoirs to this virus, said Goldstein.

So the team wondered if Arctic seals, with the ice disappearing, made their way to the Pacific and spread the PDV.

To find out, scientists looked at antibodies in North Pacific seals to see if they had been previously exposed to the virus.

They found that these populations had been infected for the first time in 2003, one year after the outbreak in the Atlantic Ocean.

But they also found another pick of infection in 2009 suggesting that exposure had continued to spread among different species, up in the Arctic.

Dr. Goldstein discusses the conclusion of the study in the video at the beginning of this article.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Canada’s Arctic, boreal birds will be big climate change losers, CBC News

Finland: Finland’s endangered Saimaa ringed seal population reaches 400, Yle News

Greenland: Oldest Arctic sea ice vanishes twice as fast as rest of region, study shows, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: In Arctic Norway, seabirds build nests out of plastic waste, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Russian Arctic town overrun by polar bears, CBC News

Sweden: Warnings in Sweden about dangerous bacteria in Baltic Sea, Radio Sweden

United States: Heat stress that caused Alaska salmon deaths a sign of things to come, scientist warns, CBC News