To stop violence against Inuit women in Canada, ‘we need to heal generations,’ says survivor

A Labrador woman who lost both of her parents in a murder-suicide when she was a child says more must be done to tackle the root causes of domestic violence in northern and Inuit communities.

“A holistic approach really needs to take place to begin healing the communities,” Becky Michelin told The Current‘s Matt Galloway.

“Because these issues trace back so far from intergenerational trauma … there needs to be big plans in place.”

Last month, the federal government announced an unspecified amount of new funding to support shelters for Inuit women experiencing domestic violence.

According to Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada, a non-profit organization that advocates for Inuit women in this country, the rate of violence against Inuit women is 14 times higher than the national average.

The COVID-19 crisis has only exacerbated the issue. Women’s shelters across the North have had to reduce their capacity to take people in, in order to meet pandemic health measures.

Last August, the federal government pledged more than $300,000 in funding to four organizations in the Northwest Territories, to help deal with the impacts of the pandemic.

No RCMP services, shelter when mother died

Michelin said it’s important that shelters exist to support women.

When her mother Deidre Michelin was shot and killed by her partner in 1993, in Rigolet, Labrador, there was no police station in the community to call for help, and no women’s shelter where her mother could seek safety.

At the time, the nearest police officer was located 160 kilometres away, in Happy Valley-Goose Bay. There are no roads connecting Rigolet to nearby communities. It is accessible year-round by plane, and by ferry in the summer or snowmobile in the winter.

“By the time the police would have arrived there, it more than likely would have been too late already,” Michelin said.

Today, Rigolet has its own RCMP detachment and a women’s shelter. However, a lack of police resources remains a concern for many northern communities.

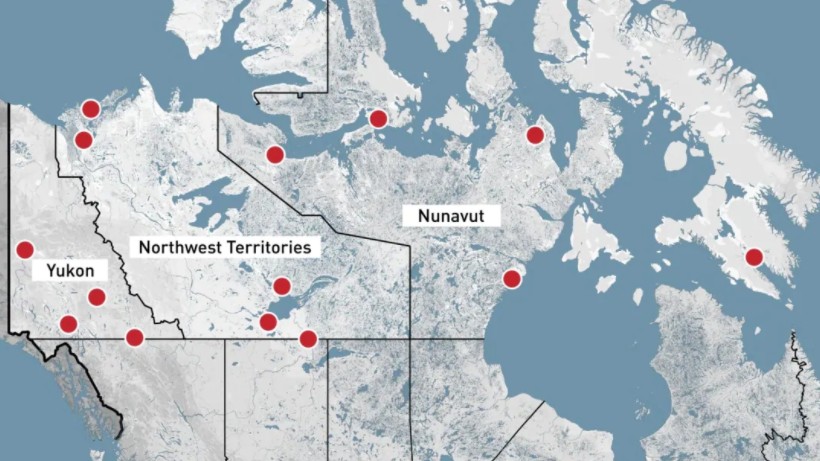

Out of 53 Inuit communities across Canada’s Arctic, 70 per cent have no shelter space where women and children can go to escape domestic violence, according to Pauktuutit.

Across Canada’s three northern territories — Yukon, Nunavut and the N.W.T. — one in three people live more than 100 kilometres away from a domestic violence shelter.

In the Northwest Territories, for example, there are just five women’s shelters serving 33 communities, many of which are remote and inaccessible by road for parts of the year.

‘Safe houses’ an alternative to shelters

Ginette Demers is the director of violence against women shelter and support services at the YWCA NWT in Yellowknife. She said it can be difficult to set up shelters for women because they require a long-term commitment and a lot of resources.

That’s why her organization is working on more flexible solution, called safe houses.

A safe house could involve a family opening up their home to a mother and her children who are in crisis, or it could be a room in a church where women find shelter, Demers explained.

“There are a lot of particular examples of what it could look like,” she said. “But it has to be informed by what the community needs and what will be feasible for the community.”

But more women’s shelters and policing services aren’t the only solution, said Michelin. She believes support services for men are critical too.

Many Indigenous people — both men and women — have experienced intergenerational trauma as a result of residential schools and colonization.

Michelin said that trauma can lead to mental health issues, substance abuse and addictions.

“These behaviours are exhibited initially as a coping mechanism, but those in direct contact learn to adapt to these behavioural patterns, thinking it’s a normal lifestyle,” she said.

“This ultimately becomes a trauma response intergenerationally, so we need to heal generations of people for this to work.”

Demers agrees.

She applauds survivors who have the courage to speak out about domestic violence, because it’s allowed for honest conversations about the impact it has on people, she said.

And although things are better today than they were years ago, she said there is still room for improvement.

“If we’re going to stop gender-based violence, we have to look at increasing healing for the entire family,” Demers said.

“These situations really are borne out of trauma and intergenerational violence, and so the cycle will not be interrupted until we can find a more holistic way.”

–Written by Kirsten Fenn, with files from CBC News. Produced by Alex Zabjek

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Nearly half of woman in northern Canada experience unwanted sexual behaviour: Statistics Canada, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Swedish-speaking Finnish women launch their own #metoo campaign, Yle News

United States: Alaska reckons with missing data on murdered Indigenous women, Alaska Public Media