Experts look at Arctic policies of region’s key players ahead of Halifax Security Forum

The future of the Arctic in an age of global warming will be a major topic at the annual Halifax International Security Forum, which convenes for the eleventh time this weekend in the Nova Scotia capital.

The Canadian event brings together some of the world’s leading geopolitical experts, politicians and military officers to discuss and collaborate on past and future matters related to international security.

In a paper, written to help frame the discussions, Thomas Axworthy, the secretary general of the InterAction Council of Former Heads of State and Government, talks about the Arctic ambitions of three major players involved in the region: Russia, China and Canada.

“In the Arctic, Russia is a superpower”

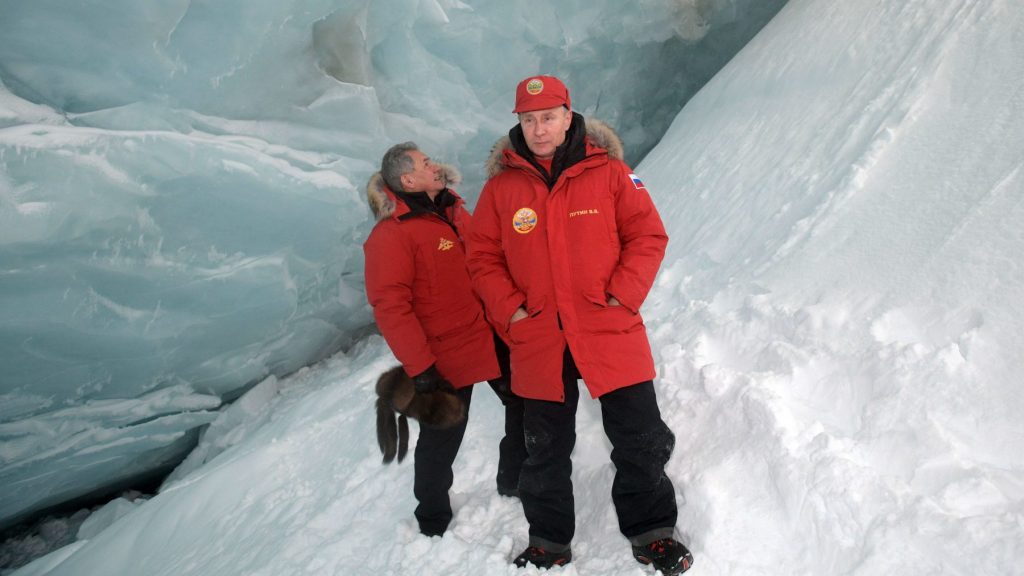

In his paper, Axworthy emphasizes on Russian President Vladimir Poutin’s interest in the region, in particular, when he endorsed the country’s new National Security Strategy to 2020.

The strategy explicitly aimed to increase the “competitiveness and international prestige of the Russian Federation”.

“The Arctic, President Putin told a meeting of the State Security Council before the strategy was officially released, was a region of ‘concentration of practically all aspects of national security—military, political, economic, technological, environment and that of resources,” writes Axworthy.

He adds that Russia is in the process of concretizing this policy with its plans to add four nuclear icebreakers to its fleet by 2035. The country will end up with a total of 13 heavy icebreakers, including nine nuclear ones.

In an interview with the French newspaper Le Figaro, Mikaa Mered, Professor of Arctic and Antarctic geopolitics at ILERI in Paris, highlights the difference between Russia and the other major military power in the region, the United States.

“Each one has a significant comparative advantage: the United States is a leader in submarines and stealth action, but Russia has a superior surface projection capability, thanks to its staff trained for cold weather operations and its icebreaker fleet, by far the largest in the world,” says Mered.

He also explained how the U.S. would struggle if they wanted to catch up with Russia as it would take a lot of time and resources to build new icebreakers.

But Mered also adds that Russia’s strategy is to work with other Arctic countries, including the United States, to counter China’s growing presence in the region if it were to become too important.

China’s growth in the Arctic is also acknowledged by the United States. This was explicitly shown by Rebecca Pincus, an assistant professor at the U.S. Naval War College, during a hearing in Washington D.C., on the implications of an emerging Russia-China alliance.

“We need to play a shaping role in this region. It’s our backyard. We have vital national interests at stake,” said Pincus. “If a Chinese submarine surfaces in the Arctic, in the next—it’s probably more like five to 10 years—that’s really going to change the game up there.”

China’s ‘Polar Silk Road’

For Axworthy, China’s latest white paper on its Arctic policy clearly shows that the country has become a powerful new player in the region.

“Despite being more than 7,000 kilometres away from the Arctic Circle, the white paper declared China to be “a near-Arctic State” and “an important stakeholder in Arctic affairs.”,” writes the expert.

The white paper clearly outlines “China’s goals in deepening the exploration and understanding of the Arctic, protecting the environment, utilizing Arctic resources, participating actively in Arctic governance, and promoting peace and stability, notably through the Arctic Council, which China joined as an observer in 2013.”

And this policy is now a reality in view of the various scientific explorations undertaken by the country as well as its two new icebreakers.

But the most important in this paper, according to Axworthy, is “the announcement that China would now include Arctic states in its “Belt and Road Initiative,” one of the most significant economic and geopolitical developments in our 21st-century world.”

As part of this plan to radically redevelop the world’s trade and transport routes, China wants to build a “Polar Silk Road” with icebreakers carrying gas between Europe and Asia via Russia’s northern shore.

According to Mered, this new road is likely to be built in view of the countries involved in this project, which are very interested and active.

He also adds that a 2018 Chinese study showed that the northeast passage was profitable during the three months of summer for a ship of 3500 containers without a reinforced hull from Shanghai to Rotterdam. The boat could do three rotations instead of two and half by the southern route.

“This perspective is therefore seen as very promising and is the starting point of the Chinese project “Polar Silk Road”,” said Mered in its interview with Le Figaro.

‘Canada’s Arctic policy is simply a laundry list of objectives’

Thomas Axworthy then looks at Canada’s Arctic and Northern Policy Framework.

Twenty-five Indigenous organizations, along with the territories of Nunavut, the Northwest Territories and Yukon, and the provinces of Manitoba, Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador (territories that are considered as Northern Canada and the Arctic within the Framework), joined in the process of creating the document.

The expert takes a rather critical position on this subject.

“It is certainly a lost opportunity: climate change, melting sea ice, and great power interest in the Arctic should make for a dynamic Arctic policy as an integral part of Canada’s most critical foreign policy priorities,” writes Axworthy. “Instead, Canada’s Arctic policy is simply a laundry list of objectives—which is neither a strategy nor even a policy.”

For him, the problem comes from the multiplicity of authors in this document. The paper “enunciates eight goals and 10 principles, but contains neither an implementation plan nor concrete policy choices.”

Axworthy also refers to Rob Huebert, a Canadian specialist in the Arctic at the University of Calgary.

Huebert says that the federal government has long been aware of the issues of health, sustainable development and sovereignty over the Northwest Passage, but “All that’s been stated before. What’s not being stated here is any idea of how the government is going to address these well-known issues.”

The author’s opinion is also shared by Heather Exner-Pirot, a Research Associate at the Observatoire de la politique et la sécurité de l’Arctique (OPSA) in her blog posted on Eye on the Arctic.

“No glossy document, no core; rather, a collection of webpages. A first phase. A handful of partner chapters that “do not necessarily reflect the views of either the federal government, or of the other partners”, with more to be released in due time.”

Axworthy concludes his article by saying that China’s White Paper, in contrast, describes the Arctic dilemma well.

“The first sentence [of China’s white paper] declares that “global warming in recent years has accelerated the melting of ice and snow” and that this poses a great security threat to China and the world.”

To address this global threat, he said, international cooperation is the only way forward, and the Arctic is a critical place to start.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Canada, U.S. must do more to check Russian military in the Arctic, says NORAD chief, CBC News

Finland: US missiles: Finnish, Russian presidents call for dialogue at Helsinki meeting, Yle News

Norway: NATO’s Arctic dilemma, Eye on the Arctic special report

Russia: Russia deploys new missile system near Norwegian, Finnish borders, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Swedish soldiers take part in Finnish naval exercise, Radio Sweden

United States: Finnish and US Presidents agree on Arctic security policies, Eye on the Arctic