Former officers from Canadian police reflect on how to fix policing in the North

Since the RCMP’s earliest days, it has relied on Indigenous people for survival.

In the North, Canada’s project of extending sovereignty over vast northern territories was made possible by the work of the RCMP and its Indigenous “special constables,” who acted as guides and interpreters.

“Our special constables … turned a lot of those RCMP members into men,” said Gerry Kisoun, who joined the RCMP in 1971 as one of the last special constables, and served as a regular officer for more than 20 years.

But that shared history has not resulted in better treatment of Indigenous people.

In the North, critics say, members run out the clock on two-year stints isolated from the communities they serve, policing according to a model that has resulted in a large number of Indigenous people dying at their hands.

Increasingly, top officials, from the RCMP’s commissioner to the prime minister, are recognizing the systemic racism that pervades the force.

Now, in the light of nationwide protests for police reform and abolition, pressure is mounting on the RCMP to devolve community safety to Indigenous communities, and reckon with their troubled history in the North.

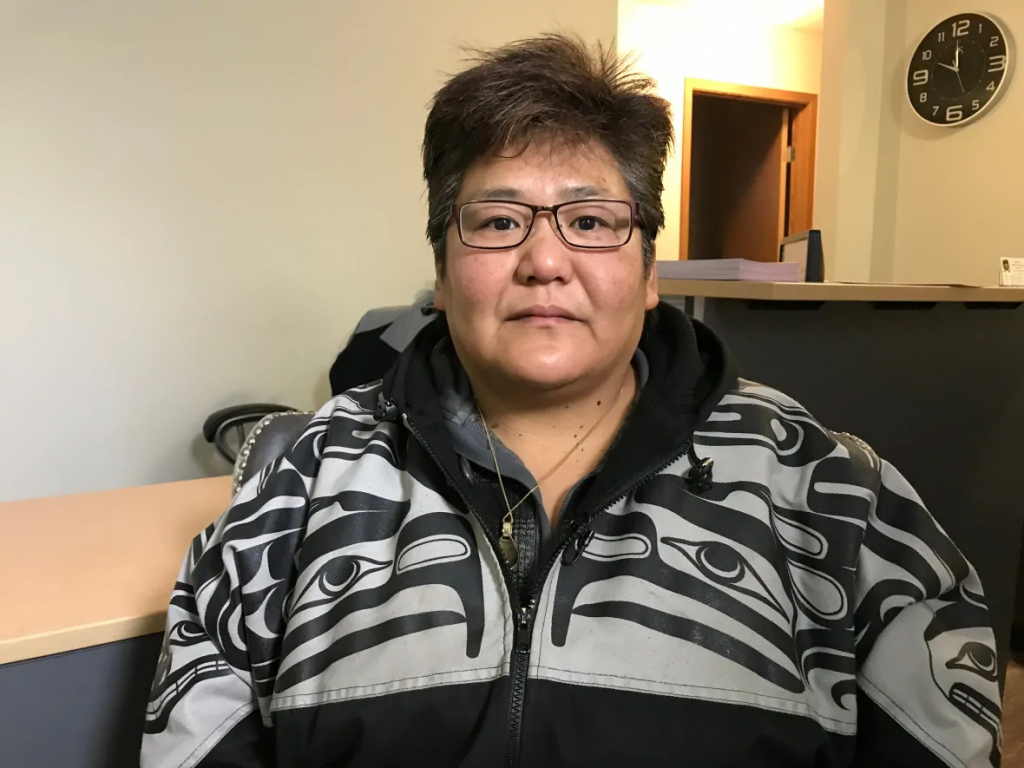

“The policing [model] in the RCMP and the policing model in our Indigenous communities are diametrically opposed,” said Gina Nagano, a Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation member who served with the RCMP from 1985 to 2006.

Complicated legacy

In the North, the RCMP has been both a source of pride and an agent of oppression.

As a child, Kisoun remembers hearing stories of RCMP officers’ daring exploits on the land of the Mackenzie Delta, enabled by the work of the Indigenous guides who inspired him to first join the force. But he remembers darker stories too.

“Some of the other stories we heard was, you gotta listen to what the RCMP say, because they’ll come into your house and scare the living daylights out of you,” he said. “That if you don’t send your kids to school, the RCMP are going to come along and throw you in jail.”

Both Kisoun and Nagano said their own experience with the RCMP, growing up, was largely positive. RCMP officers were either locals, or well-integrated into the community, they said.

“We had great police officers in Dawson City that were posted there, and always participated in community events,” said Nagano. “They were great role models.”

But the view from inside the force was quite different.

“I was surprised to see it internally, and to have it that prevalent.”

Nagano’s experience was not unique. Margorie Hudson, an Ojibwe officer from Manitoba, has launched a class-action suit against the RCMP, alleging 31 years of discrimination by her colleagues.

Kisoun acknowledged he too experienced discrimination while on the job, but said “right now, that’s neither here nor there.”

But he did say the organization’s history is a factor in the routine mistreatment of Indigenous officers and civilians.

“We’re Indigenous, and we’re going into something that was brought in by the Europeans,” said Kisoun. “And sometimes, it’s not an easy transition to go from where we are, to where they are.

“It takes a lot of work.”

RCMP disconnected from communities

Both Kisoun and Nagano said that work is not any easier today, as the force has grown more disconnected from the northern communities it serves.

“The posting is two years,” said Nagano. “It makes it really challenging for the RCMP officer to want to step out again and engage with the community.”

“But vice-versa is, the citizens are seeing that all the time,” she said. “They’re seeing the change [and] inconsistency.”

That affects trust, she said, and forces officers into “reactive policing” — the kind of work where violent incidents are more common.

“If you break those barriers down, become part of the community, get to know the citizens…. everything becomes proactive … because the community wants to work with you.”

Kisoun said it’s not enough to have better community engagement — at the end of the day, more northerners need to join the ranks.

Given several days, none of the northern RCMP detachments provided statistics on how many Indigenous people they employed.

What local control looks like

To Nagano, the solution lies outside the RCMP. After leaving the force in 2006, she worked to establish Indigenous-run community safety programs at the Kwanlin Dün and Selkirk First Nations in Yukon.

The programs employ local First Nation members to conduct patrols and intervene in situations where police would normally be called. She said it made a big difference to interactions with police.

“Most of the time, when the community safety officers engaged with … an individual, they knew who they were ahead of time,” she explained. “They knew what family they belonged to, what clan they belonged to, and they had the … understanding to approach it differently.”

If someone requires intervention, she said, “we don’t go to the probation officers. We go to grandma. We go to that elder in the community that will make that person accountable for their actions.”

Nagano has a vision for rolling out this model across the country, but the barrier is a familiar one — funding, and a lack of “political will” to make it happen.

“I think they see it as a threat,” said Nagano. “They have already had something for 100 years…. It’s a challenge for them to see someone coming in with an alternative.”

For his part, Kisoun is not holding his breath.

“There’s lots of talk in regards to self-government … and having your own policing,” said Kisoun, “but that might take some time.”

“As far as I’m concerned,” he said, “I think that the RCMP will be here for a long, long, long time.”

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Quebec Inuit org. calls lack of police, justice reform “ticking catastrophe in modern times”, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Police response times up to an hour slower in Arctic Finland, Yle News

Sweden: Film exploring racism against Sami wins big at Swedish film awards, Radio Sweden

United States: Lack of village police leads to hiring cops with criminal records in Alaska: Anchorage Daily News, Alaska Public Media