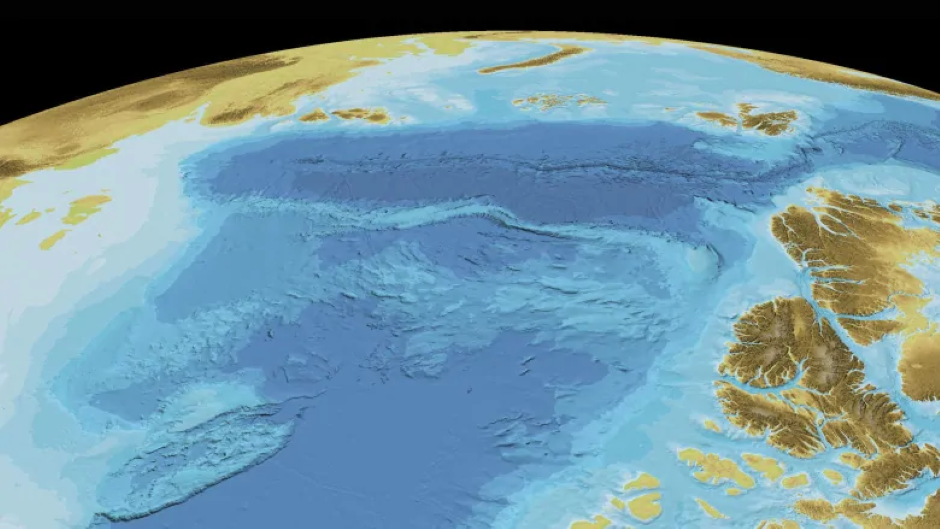

A group of international researchers has mapped more of the Arctic Ocean floor than ever before

The Arctic Ocean floor just got a little less mysterious.

A team of international researchers has compiled the most detailed map of the Arctic seabed to date. It was published earlier this month in the journal Scientific Data.

The map is part of this year’s contribution to the Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project, which seeks to map the world’s ocean floor by 2030.

“It’s truly an international effort,” said Martin Jakobsson, a professor at Stockholm University in Sweden. He co-led the scientific team of experts from 15 countries who helped produce the map.

The data was collected with the help of oceanographic vessels, icebreakers and nuclear submarines, according to the study. No other ships can reach such icy regions of the world.

The improved map — called the International Bathymetric Chart of the Arctic Ocean — will help broaden the knowledge of the sensitive region and help with future studies on the Arctic.

The map now shows almost 20 per cent of the Arctic Ocean floor. The last version, published in 2012, covered only about seven per cent of it.

Understanding climate change

The initiative to create the International Bathymetric Chart of the Arctic Ocean started in Russia in 1997, according to the journal article.

Jakobsson said it will help track climate change in the Arctic Ocean.

In his own research, for example, Jakobsson said he focuses on glaciers from the Greenland ice sheet that are melting from underneath, partly because of warming water.

“In order to know where you can have these glaciers susceptible to warm water in-flow, we must know how the sea floor looks,” he said.

A claim for the North Pole

Some of the information used to compile the map was provided by countries that have made claims to the North Pole and the seabed around it, and that have an interest in the possible resources it might contain.

That includes Canada, which, in May of 2019, submitted a scientific argument to the United Nations — 2,100 pages of evidence — for control of a vast portion of the Arctic seabed, including the North Pole.

The drive for information to make those claims to the North Pole can help establish these kinds of maps, said Rob Huebert, an associate professor in political science at the University of Calgary. His research focuses on Arctic sovereignty and security.

“The reality is that we’re still trying to determine what the Arctic Ocean looks like, even in 2020,” Huebert said. “We don’t know because of the ice cover. It’s been so difficult to have any determination.”

He says the knowledge of hydrographics is changing constantly in terms of how we understand the Arctic.

Jakobsson said his team will press on to complete the map.

“We are determined to continue,” Jakobsson said, adding he hopes to get more data from industries and countries researching the depths of the ocean.

“We have 80 per cent left, so we have a big job.”

Related stories from around the North:

Arctic: How sub-Arctic seas are influencing the Arctic Ocean and what it’s telling us about climate change, Eye on the Arctic

Canada: What ancient earthquakes along the Denali fault in Yukon can tell us about what could come in Canada, CBC News

Finland: Miners hunting for metals to battery cars threaten Finland’s Sámi reindeer herders’ homeland, The Independent Barents Observer

Greenland: Oldest Arctic sea ice vanishes twice as fast as rest of region, study shows, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: In Arctic Norway, seabirds build nests out of plastic waste, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Mass vaccination is underway on Russia’s Yamal tundra, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Warnings in Sweden about dangerous bacteria in Baltic Sea, Radio Sweden

United States: Mass grey whale strandings may be linked to solar storms, CBC News