What Gold Rush-era comedy can tell us about Canadian national identity

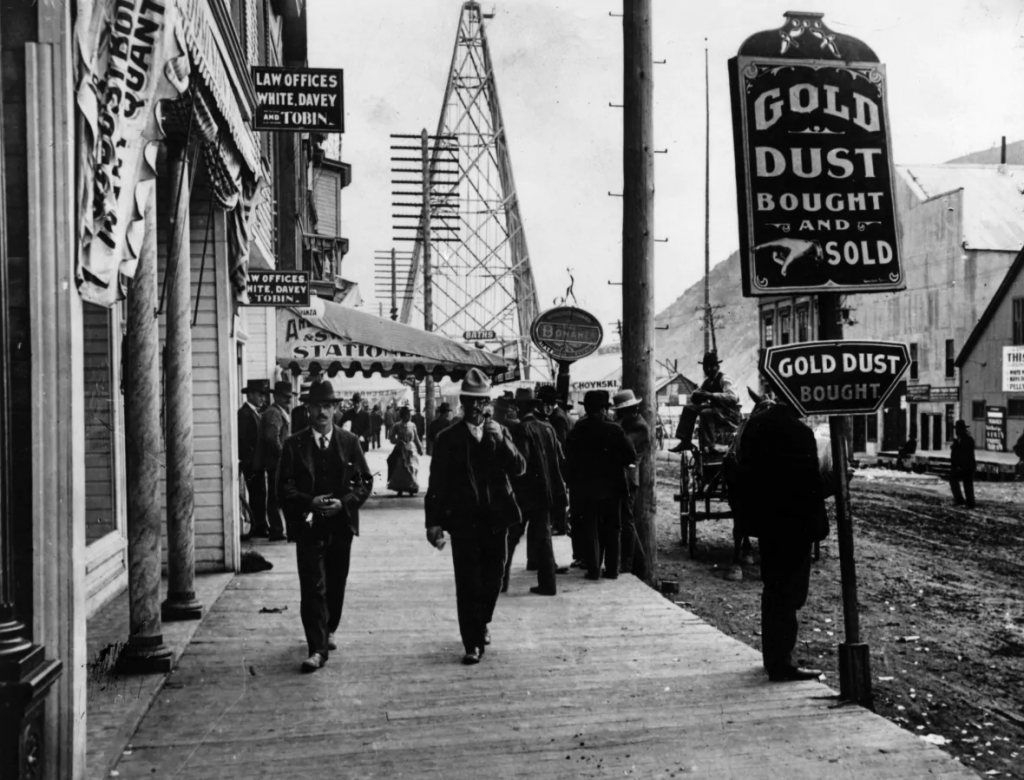

When Canadians think of the Klondike Gold Rush, they probably think of one of two things: the wild jubilation of striking it rich, or the grim misery of prospectors’ long journey north.

What they probably don’t think about are practical jokes and bawdy humour.

But that’s what Chris Petrakos, a historian at the University of Toronto Mississauga, has spent months researching.

Petrakos is a specialist in “borderlands history”, which dives into the story of “the edges of nations and empires.”

Before his latest work, he combed through records from surveyors and prospectors to explore how colonists responded to waves of mass migration from the United States by defining Canada’s northwest border.

But in the process, he struck on something no one else seems to have noticed — just how funny the residents of the Klondike could be.

“Most people don’t really discuss humour in the context of the Klondike gold rush,” he told the host of CBC’s Trail’s End.

Yet, that doesn’t mean jokes didn’t exist.

In his forthcoming paper for the journal Studies in American Humor, Petrakos writes that travellers to the North were “constant pranksters.”

“Published and unpublished travel narratives were, surprisingly, meant to be funny,” he writes.

Travel records from prominent surveyors like William Ogilvie and missionaries like the Rev. R.J. Bowen show these early colonists taking part in all sorts of practical jokes and pranks.

When Bowen first lived among a group of miners, they clogged up his stovepipe in an elaborate practical joke. It was when he emerged from his smoke-filled shack not in anger, but with a good-natured humour, that he was welcomed as a member of the community, said Petrakos.

It’s moments like these, and like the bawdy saloon-house skits that, in the words of one diarist, “made brothers out of strangers,” that Petrakos is most interested in.

Dark side to humour

While humour brought white settlers together, it also helped distance them from Indigenous people.

He told the story of Ogilvie’s visit to Fort Chipewyan, where he and his crew hosted a party for the fort’s residents.

When Jimmy Flett, an Indigenous man, showed up more handsome and pampered than any of Ogilvie’s crew, Ogilvie paid an old woman to disturb Flett on the dance floor with a “crazy … sexual dance.”

“Ogilvie writes that this creates roars of laughter from everyone at the party,” he said.

He said Flett eventually left, reinforcing the colonists’ social hierarchy for another day.

Jokes reveal shifting national identities

Petrakos said studying these japes can reveal a lot about the time period, when both Canadian and American identities were in flux.

“For Americans, it’s about defining themselves after the American Civil War. And in Canada, the nation was just created,” he said.

“They’re not just talking about their travels … they’re defining what is Canada and what is the United States.”

Those definitions changed with time as the frontier region became more settled — and more serious.

In his paper, Petrakos cites William Douglas Johns, a journalist from Chicago who travelled north to cover the very first days of the gold rush.

“Miners were great jokers in the early days,” Johns wrote, “before the discovery in ’96 gave them other things to think of.”

Petrakos’s paper is set to be published this fall.

Based on an interview by Lawrence Nayally, produced by Chris MacIntyre

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Greta Thunberg look-alike in Yukon gold rush photo sparks online frenzy, CBC News

Norway: Walt Disney Animation Studios to release Saami-language version of “Frozen 2”, Eye on the Arctic

United States: American cartoonist says his new book on Canadian Indigenous history helped decolonize part of himself, CBC North