Inuit land claim org in Arctic Quebec lowers flags after remains of 215 children found in residential school mass grave

Makivik Corporation, the land claims organization in Nunavik, the Inuit region of Arctic Quebec, lowered their flags on May 31 in memory of the 215 children found in a mass gave on the grounds of a former residential school in western Canada, the organization said on Monday.

The site of the remains was made public on May 27 by the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation in the western Canadian province of British Columbia after ground penetrating radar confirmed the finds. The survey was done on the former site of the Kamloops Indian Residential School.

“Each one of those 215 children had a family who loved them,” Pita Aatami, Makivik Corporation’s president, said in a news release.

“Each one of them had been ripped away from those families because they were Indigenous. The legacy of residential schools is an unrelenting horror. There is no escaping the fact that there will be more of these discoveries. Many children went missing. It is time to search the grounds of all residential schools and bring them home.”

Effects of residential schools still felt in communities today, says Makivik

The history of residential schools in Canada dates back to the 1800s.

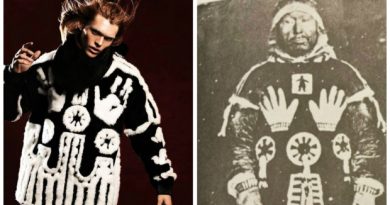

Inuit and First Nations children were sent to the federally funded, primarily church-run schools, far from their communities and their cultures, and often against the wishes of their families.

The goal was to assimilate the children into ‘European’ culture and abuse was rampant in many of the institutions. Many of the social problems in Indigenous Canadian communities have been traced back to the trauma suffered by children who passed through the schools.

“Many Inuit children from Nunavik attended residential schools,” the Makivik news release said.

“The lasting effects have led to intergenerational trauma which is evidenced in the high rate of suicide, school dropouts, unemployment, and violence in our communities. Health officials and the Inuit population have known for years that the residential school era holds much of the blame for the social challenges Inuit face.”

Over 130 of the institutions were located across Canada and more than 150,000 Inuit, Métis and First Nations children passed through the residential school system, found the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a body set up as part of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, a class action settlement set up to help former students.

The last residential schools were closed in Canada in the 1990s.

Write to Eilís Quinn at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: COVID-19 delays delivery of apology to Inuit residential school survivors in Atlantic Canada, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Finnish gov agrees to formation of Sámi Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Yle News

Sweden: Sami in Sweden start work on structure of Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Eye on the Arctic

United States: Alaska reckons with missing data on murdered Indigenous women, Alaska Public Media