Blog: The Arctic Circle’s comeback

Following a hiatus last year due to the global pandemic, and instead shifting to virtual presentations for much of 2020 and after, the Arctic Circle conference returned to Reykjavík this year, with a more modest schedule but still with much to discuss.

With stringent access rules for participants, including antigen testing on the lower level of Harpa, the conference’s venue, and the wearing of multicoloured bracelets to signify the elapsed time since a last test, the conference was held in person this year, with some guest lecturers also participating remotely.

The event took place in the wake of several pivotal events in the Arctic since the last such gathering in late 2019, including the handover of the Arctic Council’s chair from Iceland to Russia, the return of the United States to regional diplomacy, including talks on climate change, and the much-discussed revised European Union Arctic policy paper which was published shortly before this conference began.

Environmental changes in the Arctic, including ice erosion, shifting weather patterns, and deterioration of permafrost throughout the far north, dominated panel discussions this year, but as with previous Arctic Circles, regional political issues were rarely far from the main agenda. Amongst the keynote speakers were familiar faces from previous conferences, including US Senator Lisa Murkowski (R – Alaska), as well as First Minister of Scotland Nicola Sturgeon, who emphasised the growing number of Scottish linkages with the high north since Edinburgh released its own Arctic policy paper in September 2019.

Also delivering speeches during the opening sessions was Iceland Prime Minister Katrín Jakobsdóttir, appearing [video] shortly after the parliamentary elections in Iceland which resulted in the likely return of the governing coalition which PM Jakobsdóttir has led. Earlier in October, the Icelandic government published a revised Arctic policy [pdf] which highlighted the country’s concerns about climate change, while also calling for respect for international law and the peaceful settlements of regional disputes.

Regional cooperation, security & policy positions

Danish Foreign Minister Jeppe Kofod spoke about promising examples of regional cooperation [video], including in balancing environmental responsibility with economic development for the benefit of Arctic citizens. Virginijus Sinkevičius, European Union Commissioner for the Environment, Oceans and Fisheries, had the difficult task [video] of detailing the new EU Arctic White Paper, which included a call for a moratorium on Arctic fossil fuel extraction, a stance which was met with some scepticism in oil economies Alaska, Norway and Russia.

During the Q&A session, Mr Sinkevičius responded to concerns raised that the EU was seeking to unilaterally curtail future oil and gas development in the Arctic. He insisted the organisation was not trying to issue an ‘ultimatum’, but rather that climate change would eventually end the fossil fuel industries in the Arctic if serious steps were not taken quickly.

As with the 2019 Arctic Circle, Greenland featured prominently in this year’s panels and debates, including a keynote presentation [video] by Naaja Nathanielsen, Minister for Housing and Infrastructure as well as Justice, Minerals and Gender Equality. She spoke [video] of Greenland’s emergence as a regional partner, as well as outlining the intentions of the new government of Prime Minister Múte Bourup Egede towards banning uranium mining and halting further oil and gas exploration in the country.

Justice, Minerals and Gender Equality, Greenland. ( Arctic Circle)

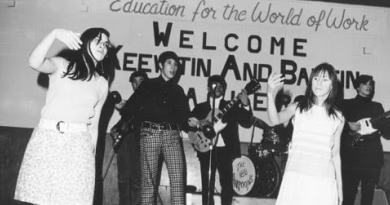

There were also panels examining issues including education, West Nordic security concerns [video], deepening government-to-government cooperation, (and possible free trade), with Iceland [video], and regional diplomacy. As well, participants enjoyed a Greenland Night event featuring local music and culture. The underlying theme of Greenland’s participation in the Arctic Circle this year was the need for the country to be included in the various emerging branches of regional policy discourse, stressing ‘nothing about us, without us,’.

Senator Murkowski was part of a larger US governmental delegation to speak [video] about changes to American Arctic policy under the Joe Biden administration. After a shambolic approach to Arctic affairs by the previous government, Washington is now renewing interest in the region, once again taking part in multilateral regional dialogues, including in regards to climate change (the US re-joined the Paris climate agreement in February this year), while also improving the overall American Arctic presence via new icebreakers and diplomatic strategies. The Russian government presence at the event was muted compared with previous years, but Nikolay Korchunov, the country’s Arctic ambassador, did speak remotely [video] about Moscow’s upcoming Arctic policies as Council Chair.

Arctic adjacent governments take the stage

Another staple of previous Arctic Circle events has been the showcasing of regional policies by non-Arctic states, and this year was no exception. Arctic adjacent governments including the Faroe and Orkney Islands outlined their engagement interests at the conference, while representatives of the European Union, via its new White Paper, sought to underscore its interest in deepening its interests in Arctic diplomacy and environmental discourses.

Iceland and University of Lapland), Sara Olsvig, (Former Vice Premier and Minister for Social Affairs, Families, Gender Equality and Justice / Ilisimatusarfik – University of Greenland), Aaja Chemnitz Larsen, (Member of the Danish Parliament for Inuit Ataqatigiit, Greenland), Halla Hrund Logadóttir, Director General, National Energy Authority, Iceland. (Arctic Circle)

With an Arctic governmental white paper expected to be published by France in the near future, Olivier Poivre d’Arvor, Ambassador for Polar and Maritime Issues, spoke about the core of current French Arctic policy being ‘science, science and science again’ [video]. Works by other non-Arctic states, including Britain, Latvia and Poland, were also featured in panels dedicated to regional science diplomacy.

Science was also on the agenda during the presentation by Jongmoon Choi, Vice-Foreign Minister of the Republic of (South) Korea, who accentuated [video] the need for ongoing diplomacy, including via the Arctic Council, between Arctic and non-Arctic actors. He also noted Korea’s contributions to Arctic science, via partnerships, regular dialogues with China and Japan, as well as research undertaken by the Korean icebreaker Areon, (with another research icebreaker, dedicated to Arctic missions, planned for 2027). It was also announced during the conference that Tokyo would be hosting [video] an Arctic Circle Breakout Forum in March 2022, in conjunction with the Sasakawa Peace Foundation.

Although there was not a high-level governmental delegation from China to the conference this year, the country’s role in the Arctic was nonetheless discussed during several different panels. There were also presentations [video] about the status of the Beijing-backed Polar Silk Road, which was described as progressing, despite several setbacks with proposed PSR projects in the Nordic region resulting in this part of the Belt and Road being more fully concentrated in Russia and East Asia.

In addition to the Tokyo Forum, another major announcement at the Arctic Circle this year was the inauguration [video] of the Frederik Paulsen Arctic Academic Action Award, which recognises scientific achievement in the combatting of regional climate change. The prize was awarded to Professor Trevor Bell (Memorial University, Newfoundland) for his work in developing the SmartICE Project, an endeavour which integrates Indigenous knowledge with monitoring technology to measure changes in local sea ice patterns for the protection of communities and maritime transits.

As the Arctic Track II network in the Arctic begins to revive following the global pandemic, there will continue to be debates over what has changed and what hasn’t, in the Arctic, during the past two years. With the return of the Arctic Circle, however, the linkages between policymakers and specialists in the region appear poised to be restored at a time when the far north is under an ever-brighter global spotlight.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Bennett out, Miller in on Crown-Indigenous Relations portfolio as Trudeau announces new cabinet, Eye on the Arctic

European Union: Red light, green light – The European Union upgrades its Arctic policy, Blog by Marc Lanteigne

Finland: New Finnish chair of Barents Council highlights climate challenge, The Independent Barents Observer

Greenland: Greenland to join Paris climate agreement, Eye on the Arctic

Russia: Putin says gas from Arctic Russia can provide long-term energy security for Europe and Asia, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Nordic countries discuss post-pandemic reset for emergency & crisis cooperation, Radio Sweden

United States: Inuit leaders call for “unprecedented and massive” action on climate as world leaders gather for COP26, Eye on the Arctic