Climate change could mean more wildlife disease in the Arctic, researchers say

A warming climate could mean some Arctic animals will be more vulnerable to parasites and disease-causing pathogens, according to researchers.

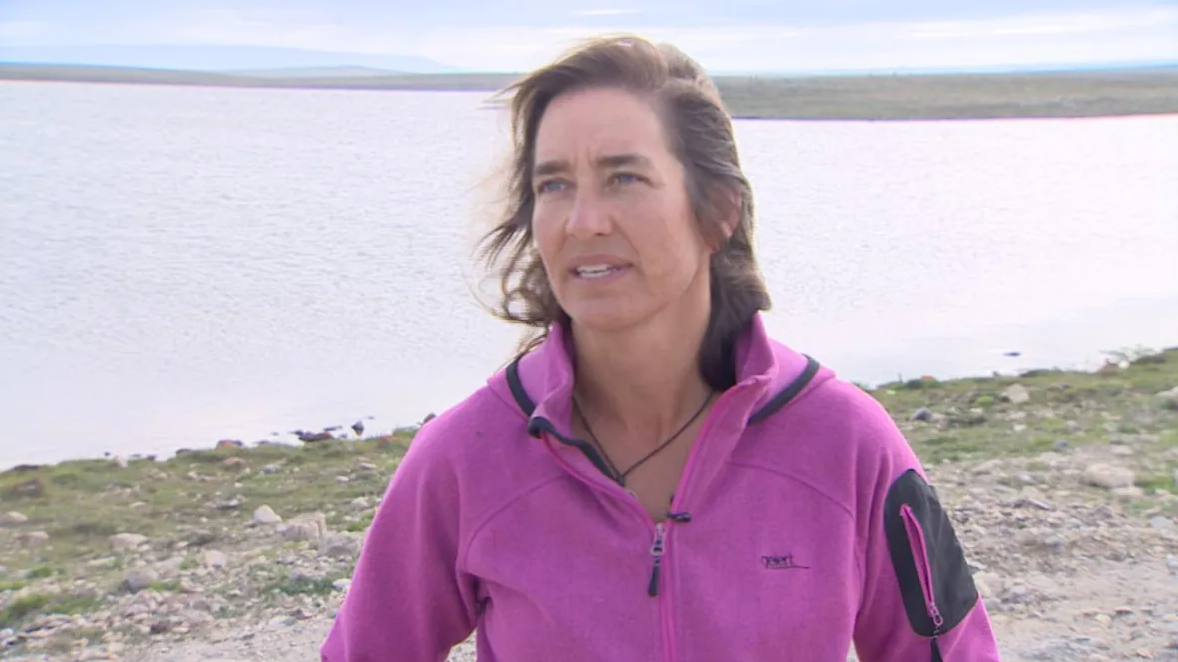

It’s a field of study where there are still far more questions than answers, says Kayla Buhler, a veterinary researcher at the University of Saskatchewan. Her work focuses on vector-borne diseases, which are transmitted from insects to animals.

A lot of her current work has involved Arctic foxes, but she’s also studied polar bears in the western Hudson Bay region. Most of her field work these days is around the Nunavut communities of Cambridge Bay and Gjoa Haven, where she works with community members there to track wildlife health and the presence of disease.

According to Buhler, the changing climate could have a dramatic impact on the transmission of disease in Arctic wildlife. That’s partly because many disease-causing pathogens are spread by insects.

“We see increases in temperature, as well as we’re seeing changes in precipitation up north — those two things are very important for insects,” Buhler said.

“Sometimes with some viruses in mosquitoes, the warmer the temperatures get, the easier a mosquito can transmit those viruses. So, temperature is a very important factor when it comes to insect-borne diseases.”

Various forms of transmission

Earlier this year, Buhler and a team of researchers published a paper on pathogens, climate, and the western Hudson Bay polar bear population. The researchers studied data from the 1980s and 1990s and found a correlation between the prevalence of pathogens among bears and warmer summers.

Buhler suggests that warmer summers mean that bears are spending less time hunting on the sea ice and more time on land — where they’re more exposed to disease-causing bacteria.

“Of course, if they’re spending more time on land, they probably will be exposed to more insect bites. So that’s the first way that it might be transmitted,” she said.

Other ways, she says, may be through contact with infected water on land, or other bacteria-transmitting species such as rodents.

Buhler argues that climate change and the diminishing Arctic sea ice will therefore “definitely impact the amount of pathogens that bears get exposed to,” by forcing them onto land more often.

Climate change will also affect the vegetation in the North, and therefore the health and size of migratory bird populations, she says — adding the migratory birds can also be a “almost like a vehicle” for insects such as fleas.

Last year, Buhler and another team of researchers published a paper describing how a bacterium that causes cat scratch fever was found in blood collected from Arctic foxes near Karrak Lake, Nunavut. Those foxes prey on migratory geese in that area, and the researchers hypothesized that a flea found in goose nests was the likely source of transmission of the bacterium.

“It’s really important to look at the relationship between migratory birds and their impacts on disease transmission in the Arctic. And so that’s kind of the next step and that’s what we’re hoping to focus on this summer,” she said.

‘A big gap’ in some wildlife population research

Buhler says one of the main aims of her research is to help create a baseline of data about disease in Arctic wildlife, to track future changes. Such data is sorely lacking, she says.

“It’s virtually impossible to take a look back, you know, 20 or 30 years, if you don’t have the samples to go back to. So that’s why we’re trying to create a baseline so that future scientists can look at our data and see if there’s any changes,” she said.

“Sometimes it’s not even something new, right? We just may never have looked for it before.”

Susan Kutz, a professor of veterinary science at the University of Calgary, agrees. She’s done research on parasites in caribou and muskoxen in the Canadian Arctic and says there’s still “a very incomplete story of what’s out there.”

“Pathogens in general have been sorely neglected in wildlife management and to a large part, I think that’s because we don’t understand them,” Kutz said.

She argues that there has been a lot of research over the years on caribou populations and how they’re changing, “but a big gap in those models has been the absence of considering the role of pathogens.”

Kutz also says there’s even less known about pathogens among species considered lower-priority for subsistence needs in northern communities, such as Arctic hares or lemmings.

Like Buhler, Kutz has done a lot of work in the Cambridge Bay area, as well as Kugluktuk, Nunavut, and Ulukhaktok, N.W.T. She says she relies on the knowledge and experience of northerners, and that survey data and samples supplied by hunters are invaluable in helping build a baseline of data on wildlife health.

“They have close connection to the land, a long history with the land. So when things change, they will see it and recognize it. They’ll have the context to see it and recognize it much better than a researcher that goes up there once a year,” she said.

Kutz hopes to see more emphasis in the scientific community on pathogens and wildlife disease, particularly in the Arctic. She says the Arctic environment is changing faster than many places on earth but it’s also a relatively simple one to study and monitor, compared to tropical ecosystems or those more affected by other human-caused changes.

“So what that does is allows us to really investigate the impact of climate change on host-pathogen interactions,” she said.

“The science we do in the Arctic, whether it’s on parasites or pathogens, or in other fields, it’s really important for understanding global climate change.”

Kutz also suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic may shift some priorities in the scientific world.

“I do believe that despite all the bad it’s done,” she said, “the current pandemic has definitely raised the profile of infectious disease, the importance of understanding it.”

With files from Laureen Laboret

Related stories from around the North:

Arctic: Arctic Report Card 2021: Sea ice changes, rain on Greenland ice sheet among dramatic changes in North, Eye on the Arctic

Canada: Int’l protocols for working with Inuit knowledge one step closer as workshops wrap up, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Temperatures headed toward -40C in Finnish Lapland, Yle News

Greenland: Blog: Radical Arctic warming – rain, rain, here to stay?, Marc Lanteigne

Norway: The Arctic Railway – Building a future or destroying a culture?, Eye on the Arctic

Russia: WMO confirms 38 C Arctic temperature record in Russia, Eye on the Arctic

Sweden: January temperatures about 10°C above normal in parts of northern Sweden, says weather service, Radio Sweden

United States: Scientists warn of Arctic microbial threats induced by climate change, Eye on the Arctic