Blog: Thawing permafrost: Arctic future on shaky ground bodes ill for the global climate

When I first visited Greenland on a reporting trip in the summer of 2009, my first stop, like that of most international visitors arriving by air, was Kangerlussuaq, a settlement in the central-western part of the world’s biggest island. Located at the inner end of a long fjord, it has the atmosphere of being in the “middle of nowhere”. But is one of only two civilian airports in Greenland with a runway that can take large aircraft, so the hub for international flights.

Kangerlussuaq is scattered around the airport, which is the reason for its existence. It was founded as a US Air Force base in 1991. Today, it has fewer than 500 residents. Accommodation and facilities are limited. Visitors only tend to stay long enough to make a trip along the road out to the ice sheet some 25km away, or fly on to other places in Greenland.

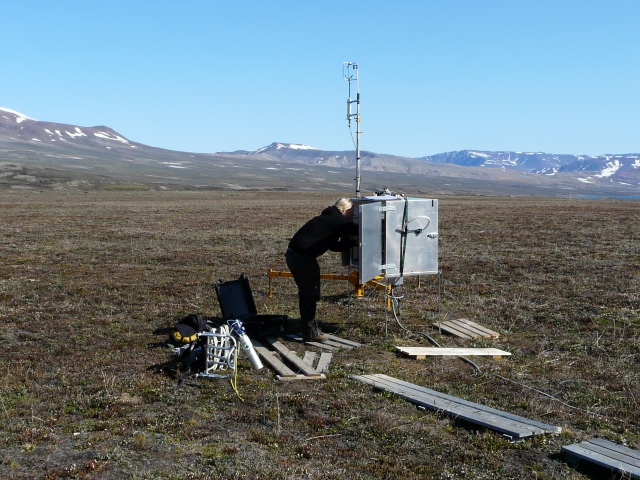

Walking around Kangerlussuaq, some odd-looking structures under some of the buildings caught my eye. Pipes going into the ground, frozen over. My local guide explained that this was a cooling system to work against the thawing of the permafrost on which the houses were built, and so protect the foundations and stop them collapsing. That seemed to me like a bit of a paradox – using electricity generated by fossil fuels to protect against climate warming caused by that very process. It was also a pointer to a phenomenon that is threatening life in Arctic regions – and the global climate.

Permafrost is ground below the Earth’s surface that has been continuously frozen for at least two consecutive years and in most cases, for hundreds or thousands of years. It actually covers about nine million square miles, a quarter of the Northern Hemisphere, including a lot of regions that are not covered in snow. Large parts of Alaska, Canada and Siberia, where people, mostly indigenous communities, have lived, worked, and hunted for hundreds of years, are situated on permafrost. As the world warms, the icy layers in the ground are thawing. The surface becomes softer and sags.

Gateway to the ice sheet

During a later visit to Kangerlussuaq in 2017, I interviewed Professor J.P. Steffensen, a glaciologist from the University of Copenhagen. He was in charge of the logistics for the East Greenland Ice-core Project, or EastGRIP, and arranging to get scientists and equipment out to the project site.

The aim of the project is to drill and retrieve an ice core from the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream (NEGIS), out on the massive ice sheet, the second largest ice body in the world after the Antarctic ice sheet. Its ice covers 1,710,000 square kilometres, roughly 79% of the surface of Greenland. The ice sheet is almost 2,900 kilometres long in a north–south direction, and at its widest, it is around 1,100 kilometres, near its northern margin.

Kangerlussuaq airport is a key facility for the scientists flying out to the ice sheet. Its runway can take the Hercules aircraft, which can transport equipment and land on skis on the ice.

Climate archive in the ice

The ice sheet is formed by snow that falls year after year and remains, gradually being compressed into an ice sheet several kilometres thick. By drilling ice cores through it, researchers can see each annual layer and measure what the temperature was in the precipitation that originally fell as snow. In this way, they can determine what the climate was like over more than a hundred thousand years – how warm it was and how much precipitation fell.

Professor Steffensen – or P.J. as he is known – told me he and his fellow scientists were very concerned about plans for the airport to be shut, with the authorities wanting to shift air traffic to the capital, Nuuk and the popular tourist destination Ilulissat. That would be a huge blow to the scientific operations. Alas, the airport has a climate-related problem. In 2019, “Permafrost thaw will force Greenland’s Kangerlussuaq Airport to close to most commercial traffic in 2024” was the headline of an article by Malte Humpert in Arctic Today. Damage to the runway was fist documented back in 1973, Humpert wrote. These days, part of the runway is estimated to be sinking by more than two and a half centimetres every year.

Kangerlussuaq airport has received a kind of “stay of execution”, thanks to Danish government-funded repairs to keep it usable for the military – but that’s another story. For the scientists working on the ice sheet, that was very good news. But the underlying threat from thawing permafrost has not gone away – and Kangerlussuaq airport is just one striking example of the threat to the infrastructure of the Arctic region, which is home to almost four million people.

Sagging ground, collapsing infrastructure

Roads, houses, pipelines, military facilities and other infrastructure are collapsing or starting to become unstable. A study published by the University of Helsinki on January 12, 2022, found that “the thaw of permafrost is set to damage buildings and roads, leading to tens of billions of Euros in additional costs in the near future”.

Professor Jan Hjort from the University of Oulu and his colleagues reviewed published research on the permafrost area of the whole Northern Hemisphere.

“The warming and thawing of ice-rich permafrost pose considerable threat to the integrity of polar and high-altitude infrastructure, in turn jeopardizing sustainable development”, the scientists write. They found damage was lowest in the European permafrost area, such as the Alps and Svalbard, greatest in Russia. Two thirds of the country rests on permafrost.

Up to 80% of buildings in some Russian cities and around 30% of some road surfaces in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau had reported damage. As global warming continues, Hjort and his colleagues say 30–50% of “critical circumpolar infrastructure” is thought to be at high risk by 2050. That means permafrost degradation-related infrastructure costs could rise to tens of billions of US dollars by the second half of the century.

The world’s permafrost has been warming at between 0.3 and 1.0 degrees Celsius per decade since the 1980s, with some areas of the High Arctic having increased by more than 3 degrees Celsius over four decades. That is enough to thaw much of the frozen ground. This trend is set to continue as climate change proceeds. From satellite imagery, the experts estimate that at least 120,000 buildings, 40,000 km of roads, and 9,500 km of pipelines could be at risk. They highlight threats to some Canadian highways, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System and the Russian cities of Vorkuta, Yakutsk and Norilsk.

Nearly 70% of current infrastructure in the permafrost domain is in areas with high potential for thaw of near-surface permafrost by 2050.

This is permafrost, backbone of the Arctic and the most mysterious part of the cryosphere. Permafrost is hidden from our sight, buried under a layer of vegetation, litter, and peat. Yet it underlays a quarter of land in the Northern Hemisphere, half of Canada, and most of Alaska. pic.twitter.com/xqCpgAnVUd

— Dr. Merritt Turetsky (@queenofpeat) January 27, 2022

Siberia on thin ice

In an article for the New Yorker entitled “The Great Siberian Thaw”, Joshual Yaffa describes a trip to north-eastern Russia:

“In Yakutia, where the permafrost can be nearly a mile deep, annual temperatures have risen by more than two degrees Celsius since the Industrial Revolution, twice the global average. As the air gets hotter, so does the soil. Deforestation and wildfire – both acute problems in Yakutia – remove the protective top layer of vegetation and raise temperatures underground even more”. He explains how microbes in the soil awaken as the permafrost thaws, and feast on the defrosting organic material, which has been stored there for thousands of years. It releases “a constant belch of carbon dioxide and methane”, Yaffa writes.

Still, building continues in the Arctic. As the region warms and interest in the natural resources and other development potential grows, the need for new roads, railways, pipelines and buildings is increasing. Reporting for Reuters, Gloria Dickie quotes another study published in Environmental Research Letters last year, which used satellite images and concluded coastal infrastructure has increased by 15 percent, or 180 square kilometres (70 square miles), since 2000.

Stabilising the frozen ground to secure the infrastructure is a costly business.

Permafrost thaw threatens up to 50% of Arctic infrastructure https://t.co/AVUkqkxCEh pic.twitter.com/mAsQ00H1v8

— Prof Jamie Woodward (@Jamie_Woodward_) January 13, 2022

The vicious climate circle

This is part of the huge paradox that is Arctic warming. Exploiting fossil fuels has led to the warming that is opening the High North to further development – and at the same time destroying the infrastructure essential for that development to continue.

Russian President Putin views the warming of the north primarily as an opportunity for economic development. In a commentary for the New York Times, Thomas L. Friedman considers a speech by US-President Biden against the background of the Ukraine conflict. He points to a statement he says was missed by most of the media –“the one that may turn out to be the most prescient”, he suggests. “You had to be listening closely because it went by fast. It was when Biden told President Vladimir Putin that Russia has something much more important to worry about than whether Ukraine looks East or West – namely, “a burning tundra that will not freeze again naturally.”

As world leaders continue working in Glasgow/UN Climate Change Conference, here is our postcard from Siberia, highlighting recent major changes:bubbling methane in the Arctic, peat fires burning at -50C, giant craters peppering the Yamal peninsula, & more https://t.co/t55KLVlEsa pic.twitter.com/xpxr8EYxCM

— The Siberian Times (@siberian_times) October 31, 2021

Friedman is convinced climate change in Siberia will threaten Russia’s stability a lot more than anything that happens in Ukraine. He predicts that more and more leaders will have to shift from building their popularity “only on the strength of their resistance to enemies abroad and at home”, to increase their stature by “generating resilience for their people and neighbours in a warming and water-stressed world.” He mentions the rare unseasonal tundra fire in Siberia last November and the risk of desertification in southern regions of Russia’s vast territory.

Permafrost carbon feedback – a global problem

As well as the direct, local consequences of thawing permafrost – the impacts on the people who live there, on wildlife, ecosystems and infrastructure – the warming north has potentially catastrophic consequences for the planet as a whole. The carbon and methane emissions from the no-longer-frozen ground adds to the greenhouse gases already causing us so many problems, in what scientists describe as a kind of “feedback loop.”

In another study published in January 2022 in Nature Reviews Earth & Environment „Permafrost carbon emissions in a changing Arctic”, Kimberley R. Miner, Merrit Turretsky, Edward Malina and colleagues focus on “the permafrost carbon feedback”. They review research so far and outline the need for widespread further monitoring.

Thank you @NatRevEarthEnv for the focus on permafrost change. A reminder that permafrost thaw in the Arctic will make it more difficult for us to meet climate policy targets. Permafrost is the foundation of the Arctic from climate feedbacks to infrastructure to food. https://t.co/YMw6yiQNrW

— Dr. Merritt Turetsky (@queenofpeat) January 21, 2022

They note that Arctic permafrost stores nearly 1,700 billion metric tons of frozen and thawing carbon, and that human-induced warming threatens to release an unknown quantity of this carbon to the atmosphere, influencing the climate in processes collectively known as the permafrost carbon feedback. The authors say abrupt changes could release a substantial amount of carbon as well as methane to the atmosphere rapidly, in “days to years”.

Increasingly frequent wildfires in the Arctic will also lead to a “notable but unpredictable carbon flux”, they write. More detailed monitoring on the ground, from the air and by satellite observations will provide a deeper understanding of the Arctic’s future role as a carbon source or sink, and the subsequent impact on the Earth system, they say. Potentially, climate warming and the resulting thaw could convert the Arctic from a carbon sink to a carbon source.

The permafrost factor is of key importance to predicting how our climate will develop. Unfortunately, exactly how it will pan out is highly uncertain. More monitoring and research are essential to improve projections of “the locations, magnitudes and speeds of permafrost carbon release”. Permafrost dynamics are often not included in Earth system models (ESMs), the scientists note.

So much we don’t know

Another study published last month by scientists from Cologne University in Germany working in the Siberian Arctic found that thawing permafrost could be “emitting greenhouse gases from previously unaccounted-for carbon stocks, fuelling global warming.”

In the Siberian Arctic, the research team determined the origin of carbon dioxide released from permafrost that is thousands of years old. A large proportion of the carbon — up to 80 per cent — comes from ancient organic matter that was freeze-locked into the sediments more than 30,000 years ago. This means that vegetation remains that died thousands of years ago have been very well ‘preserved’ in the frozen sediment, making them an attractive food source for microorganisms in the thawing permafrost. But the team also found out for the first time that up to 18 per cent of carbon dioxide comes from inorganic sources.

“We did not expect that this previously unnoticed carbon source would account for such a high proportion of the total amount of greenhouse gases released,” said first author of the study Jan Melchert from the University of Cologne. “For more precise climate predictions, it would be necessary to take this source into account.”

Future research will have to clarify where exactly the inorganic carbon comes from and through which processes it is released.

Why should you care about what's happening in the Arctic?

Because it impacts the entire planet.🌍

Without #ClimateAction, thawing permafrost could release dangerous microorganisms & carbon emissions that have been locked in ice for thousands of years. https://t.co/PMalyx3NAD

— United Nations (@UN) February 6, 2022

A neglected factor in the climate equation

The United Nations recently published a piece entitled “If you’re not thinking about the climate impacts of thawing permafrost, (here’s why) you should be “.

The story goes on: “As this phenomenon reshapes landscapes, displaces whole villages, and disrupts fragile animal habitats; it also threatens to release dangerous microorganisms and potential carbon emissions that have been locked in ice for thousands of years. “ The UN quotes Susan M. Natali, a scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, who has been studying permafrost thawing in the Arctic for over 13 years. Dr. Natali explains that while we can’t now reverse permafrost thaw – because it has already started – “ambition is key to avoid the worst of it.” Hers is a sobering conclusion:

“I think even under our most ambitious scenarios (for reducing global carbon emissions and subsequent warming), we’re going to lose, you know, probably 25 per cent of surface permafrost, and then some of the carbon that’s in there will go to the atmosphere. But this is much better than less ambitious scenarios which could take us to 75 per cent thaw. Permafrost is a climate change multiplier and so it needs to be an ambition multiplier,” she stresses.

If we do not incorporate feedback effects such as greenhouse gases resulting from frozen ground thaw into the calculations, it will be virtually impossible to reach the 1.5C target of the Paris Agreement, Natali argues.

Blog: Arctic SOS to Climate COP26 – urgent action needed to avert weather catastrophe

“It’s a big enough challenge to get nations to make the commitments and take action. But imagine that we’re not even aiming for the right target, which is essentially what’s happening right now because we’re not even doing the math right, because permafrost is not properly and fully accounted in the bookkeeping, and because people aren’t thinking about it,” she warns.

Dr. Martin Sommerkorn, Head of Conservation of the WWF Arctic Programme, is also coordinating lead author of the Polar Regions Chapter of the IPCC Special Report on Oceans and Cryosphere. He told UN News the changes to the cryosphere and the effects in the polar regions could no longer be regarded as an early warning signal.

“They are driving climate change and impacts globally,” Dr. Sommerkorn stressed.

Can we keep the “perm” in “permafrost?

The authors of the Helsinki University assessment of the threat to infrastructure note that there are several mitigation techniques to alleviate these impacts, “including convection embankments, thermosyphons and piling foundations, with proven success at preserving and cooling permafrost and stabilizing infrastructure.”

However, the economic cost, they say, is often too high. We also still understand too little. “Greater efforts are needed to quantify the economic impacts and occurrence of permafrost-related infrastructure failure”, the experts write. They say future development projects should conduct local-scale infrastructure risk assessments before commencement.

But when it comes to the global problem created by permafrost carbon feedback, the situation is far more complex. This is one of the feedback loops which could run out of control.

”We know, categorically, that humans have triggered a planetary warming trend that demands an urgent global campaign of decarbonisation”, said John Holdren, Professor of Environmental Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government and former Director of the Obama White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. He was speaking at one of a series of Dialogue meetings organised last year by the Permafrost Carbon Feedback Action Group (PCF).

“We also know the intensifying potential of thawing permafrost – a fragile storehouse containing twice as much carbon as in all the earth’s atmosphere. But we don’t know how quickly permafrost is thawing, how fast it is emitting greenhouse gases, or what countermeasures might mitigate the problem.”

Long-frozen #permafrost is thawing, releasing vast amounts of methane, a potent greenhouse gas. What are the implications of this and what does it mean for our climate future? @novapbs investigates: https://t.co/G0SNGk0D4p

— National Snow and Ice Data Center (@NSIDC) February 3, 2022

No going back

Holdren is clear on one thing: “We need to invest in adaptation technologies, because we cannot stop climate change in its tracks. No matter what we do, we are going to be adapting to the actual harm”.

The experts involved in the dialogues discussed measures which might be implemented either regionally or globally to try to halt permafrost thaw. They include for instance changing land use. One example is Pleistocene Park in northern Siberia, which includes “an attempt to restore the mammoth steppe ecosystem, which was dominant in the Arctic in the late Pleistocene.” The organisers want to replace the “current unproductive northern ecosystems by highly productive pastures which have both a high animal density and a high rate of biocycling.” They are reintroducing herbivores like reindeer, bison and musk ox” which would fertilize the landscape and, amongst other things, trample down snow and help keep the permafrost cool.

Others advocate the use of styroform and geotextile coverings to cool the land.

An increasing number of experts are arguing for different forms of geoengineering, including solar radiation management.

“Even cutting emissions to zero tomorrow does not deal with the climate risk. There is evidence that a combination of emissions cuts and solar geoengineering might be significantly safer than emissions cuts alone, argues ”David Keith, Professor of Applied Physics, Public Policy at Harvard and a scientific and policy leader in geoengineering.

Our @OscarR_Rueda had the honor of presenting to Canadian senior policymakers and research leaders the role of #NegativeEmissions to meet the 1.5 °C climate target. Check the video and key takeaways:https://t.co/ToMdwYMJji@OscarR_Rueda @CascadeInst, @cpa_acp#ClimateChange

— Sustainability Priorities Research (@SustainPrior) March 23, 2021

There are, however, a lot of uncertainties relating to methods of this sort. Sulfate injection, for instance, dims the sun. That might decrease temperatures, but it also decreases the ability of plants to grow because of the lack of sunlight, explained Pam Pearson from the International Climate Cryosphere Initiative (ICCI) during the PCF dialogues. That could then impact the ability of plants in northern regions to absorb the carbon that comes out of permafrost thaw emissions, says Pearson.

There would also be risks to the environment and potentially to human health.

Cut emissions, no excuses

Another problem is that even if the permafrost refreezes, “it’s going to continue emitting for as long as a couple of 100 years,” Pearson says. Like many concerned about climate change, she is worried that experimenting with geoengineering or other techniques could be used by governments as a delaying tactic: “The focus needs to be on emissions reductions, because anything that tells governments that they can kick the emissions can down the road is enormously destructive”.

Permafrost expert Merrit Turretski told the forum permafrost carbon feedback means we have less time, perhaps four to five years less to meet the 2 or 1.5°C targets. We have to decarbonize now, she urges.

I can only agree wholeheartedly.

“We are sinking” – Tuvalu’s Minister of Justice Simon Kofe

🧊Earth’s permafrost is thawing – reshaping landscapes, displacing whole villages & disrupting fragile animal habitats

Why the permafrost melting should be on your mind to #ActNow⤵️https://t.co/zt3LIKUcQ2 pic.twitter.com/RRaV2YJ2E7

— UN Environment Programme (@UNEP) February 1, 2022

Sadly, as WWF Arctic’s Martin Sommerkorn stresses, there still is not enough general understanding of the long-term effects of changes in the frozen elements of our world at the decision-making levels.

“These changes have a direct link to the ambitions for 2030. The IPCC said it clearly: We have to reduce emissions by 50 per cent by 2030 compared to 2010 levels if we want to stay below 1.5C (warming) without overshoot, and cryosphere doesn’t grant us the luxury of overshoot… We will trigger thresholds of melting that cannot be undone. It is very, very hard to regrow glaciers. It is basically impossible to grow back permafrost under raising temperatures”, says Sommerkorn.

By reducing emissions and rates of warming, we are also reducing rates of ice melt and giving people time and methods to adapt, the Arctic expert stresses.

So – we know what we should be doing. Unfortunately, the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere is going up steadily.

📈 419.33 ppm #CO2 in the atmosphere February 8, 2022 📈 Up from 416.02 ppm a year ago 📈 Mauna Loa Observatory @NOAA data & graphic: https://t.co/MZIEphYygh 📈 https://t.co/DpFGQoYEwb tracking: https://t.co/PTTkLiPGm2 🙏 View & share often 🙏 pic.twitter.com/xuzVtYu5Qd

— CO2_Earth (@CO2_earth) February 9, 2022

2021 was the sixth warmest year on Earth since 1850, in spite of a cooling La Nina effect, and the last seven years were the warmest on record.

Speaks for itself: https://t.co/lPLF3ksEEd

— Potsdam Institute (@PIK_Climate) January 26, 2022

According to an independent analysis by Berkeley Earth, a California-based non-profit research organization, we are now at 1.2°C of global warming, and at the current pace, we will hit 1.5°C in 2033 and 2°C by 2060.

In spite of that, we are pumping more oil than ever.

This is a deep deep concern…Despite climate emergency, the United States, Canada, and Norway "pumping more oil than ever" https://t.co/JQKhzJAGCx via @priceofoil

— Johan Rockström (@jrockstrom) January 30, 2022

The IEA expects the amount of electricity generated from coal to hit an all-time high this year, “a worrying sign of how far off track the world is in its efforts to put emissions into decline towards net zero,” and a “sobering reality check of the government policies,” according to Fatih Birol, the executive director of the IEA.

There is still a huge gap between ambition and action, when it comes to the transition from fossil fuels to climate-protecting renewable energy sources.

Blog: Business as usual for fossil fuels as polar ice melt bodes more climate chaos in 2022

With the pandemic recovery and the Ukraine crisis focussing attention on energy, gas – another fossil fuel – is constantly in the headlines, supposedly to “bridge the gap” between the status quo and the renewable future. Critics fear it will slow the transition rather than speed it up.

Greenpeace chief joins German government

Against the background of the climate emergency, Germany has persuaded the head of Greenpeace International, Jennifer Morgan, an internationally-renowned climate expert, to leave the organisation and become the Berlin government’s special climate advisor.

Germany on Wednesday introduced its "dream" international climate envoy – Greenpeace chief, American Jennifer Morgan, in a bold sign it is willing to spearhead more ambitious action to tackle the global climate crisis. https://t.co/7WQJAAQcU7

— Reuters Science News (@ReutersScience) February 10, 2022

Some will see that as a headline-grabbing pr coup. Others are concerned about such close links between politics and a lobbyist. The German government and Greenpeace? Is one of the loudest critics of the lack of state action on climate change shifting sides?

Once more, the proof of the pudding will be in the eating. I will take it as an encouraging sign that the Greens in the coalition government of this key economy are going full out to fulfil their pre-election promises – and party philosophy – and drive the energy transition the world needs to halt climate change and protect the planet. I wish Jennifer Morgan and those who hired her speedy success – and good luck. We all need it. And we need it everywhere. As long as greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, the Arctic will find itself on ever-shakier ground and the risk of climate catastrophe will loom ever larger over the whole planet.

Related stories from around the North:

Arctic: Ultra-cyclist rides across entire Arctic to warn of climate change, Eye on the Arctic

Canada: How floor repair of ‘igloo church’ in Arctic Canada could offer deeper look into North’s permafrost, CBC News

Greenland: Rise in sea level from ice melt in Greenland and Antarctica match worst-case scenario: study, CBC News

Norway: Thawing permafrost melts ground under homes and around Global Seed Vault in Svalbard, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: City in Arctic Russia cooling ground to preserve buildings on thawing permafrost, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: Bering Sea ice at lowest extent in at least 5,500 years, study says, Alaska Public Media

World: 2021 one of seven warmest years on record, says U.N. agency, Eye on the Arctic