Blog: Business as usual for fossil fuels as polar ice melt bodes more climate chaos in 2022

This December brought some stark reminders of the events that made this year one I will not forget – and not be sorry to see the back of.

Our local authority, the “Rhein-Voreifel” region of western Germany, invited interested residents to a meeting about measures to make our area resilient to climate change. The meeting was particularly well attended, not least, I am sure, because climate change hit home very close here this summer with the floods that devastated the Ahr valley and neighbouring areas, killing 180 people.

Communities found themselves in shock and disbelief; that a tiny trickle of a river could swell to submerge buildings and sweep away roads and railway lines – and that our prosperous, highly developed area in technologically advanced and highly industrialised Germany was so vulnerable

Now our local authorities are getting ready for more extreme rainfall and floods, but also dry summers and droughts, lasting heatwaves, strong winds.

The meeting itself was shifted from a local hall to Zoom – in response to the other crisis facing our society. Corona is still with us, alive and kicking. Another reminder that we cannot keep treating the world as we have in the past, exploiting its natural resources as if they would last forever; encroaching ever further into nature, the wild. And we do not have everything under our control. The unpredictable has become the normal.

Alas, it is not easy to put a genie back into the bottle, whether it’s called climate change or corona.

A taste of things to come

A new analysis by scientists at Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) in December confirmed that the catastrophic flooding we experienced here in Europe this summer was not a one-off natural disaster, but a taste of things to come – and of our own making.

New study: Too #dry, too #hot, or too #wet. "In Europe alone, about 70% of the land area is already affected by more persistent #weather situations,” says PIK scientist Peter Hoffmann.

👉https://t.co/4gdLZKsHZw pic.twitter.com/ihQsTNvkcb— Potsdam Institute (@PIK_Climate) December 6, 2021

“Too dry, too hot, too wet: Increasing weather persistence in European summer”, was the title of the study published in Nature. The scientists found that global warming makes long lasting weather situations in the Northern hemisphere’s summer months more likely – which in turn leads to more extreme weather events like heat waves, droughts and intense rainy periods.

“In Europe alone, about 70% of the land area is already affected by more persistent weather situations,” said Peter Hoffman from PIK, lead author of the study, based on a novel analysis of atmospheric images and data.

“This means that people, especially in densely populated Europe, will likely experience more and also stronger and more dangerous weather events,” he explained. “Especially in summer, heat waves often last longer now, and also rainfall events tend to linger longer and to be more intense. The longer these weather conditions last, the more intense the extremes can become, both on the warm and dry side as well as on the steady rain side.’”

The new approach improves the interpretation of long-term climate impacts, according to co-author Fred Hattermann of PIK. Worryingly, applying the method to output from climate models indicates that these may have been “a bit too conservative, underestimating the rise in weather persistence – thus underestimating weather extremes over Europe.”

Expect the unexpected

There have been similar messages from many sources as 2021 draws to a close. In their coverage of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) meeting in New Orleans, which The Washington Post describes as the world’s largest climate science conference, authors Sarah Kaplan and Brady Dennis say scores of studies presented offered a clear and unsettling message:

“Climate change is fundamentally altering what kind of weather is possible, and its fingerprint can be found in the rising number of disasters that have claimed lives and upended livelihoods around the world.”

“The weather of the past will not be the weather of the future,” said Stephanie Herring, a climate scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “As long as we are emitting greenhouse gases at a historically unprecedented rate, we should expect this change to continue.”

Herring has closely tracked the link between extreme weather and climate change since 2012, when she edited the first “Explaining Extreme Events from a Climate Perspective” report for the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, the paper explains. The annual survey of “attribution science” looks at weather records and sophisticated climate models to determine the extent to which individual events were influenced by human emissions.

Experts are currently debating the extent to which tornadoes like those that devastated Kentucky this month can be attributed to the changing climate.

The Arctic as we never knew it

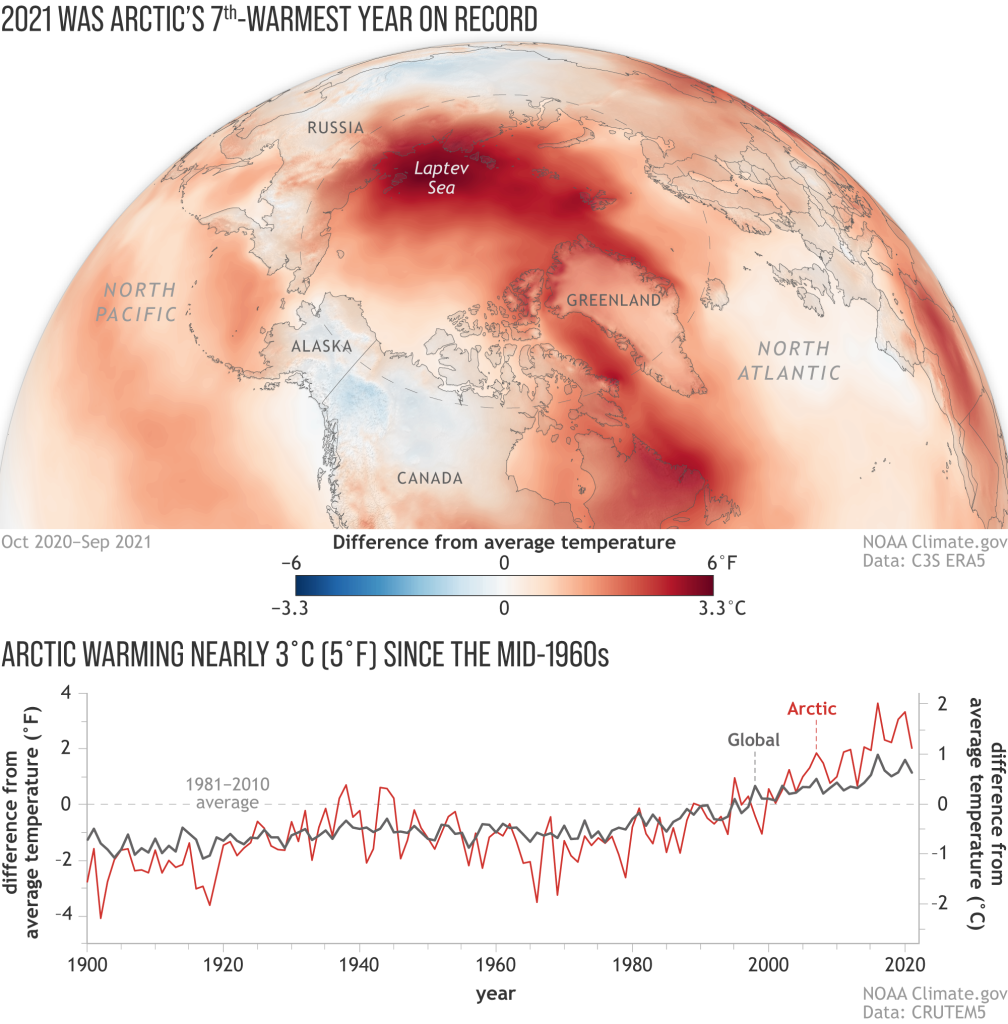

At that same AGU meeting, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released its annual Arctic Report Card. I have the feeling it did not get the media attention it might once have done – and certainly deserved. Are there just too many other things going on in the world? Or are we getting so used to hearing about dwindling sea ice, thawing permafrost and melting ice sheets that this documenting of the “numerous ways that climate change continues to fundamentally alter this once reliably-frozen region, as increasing heat and the loss of ice drive its transformation into a warmer, less frozen and more uncertain future” don’t make for an attention-grabbing news story these days?

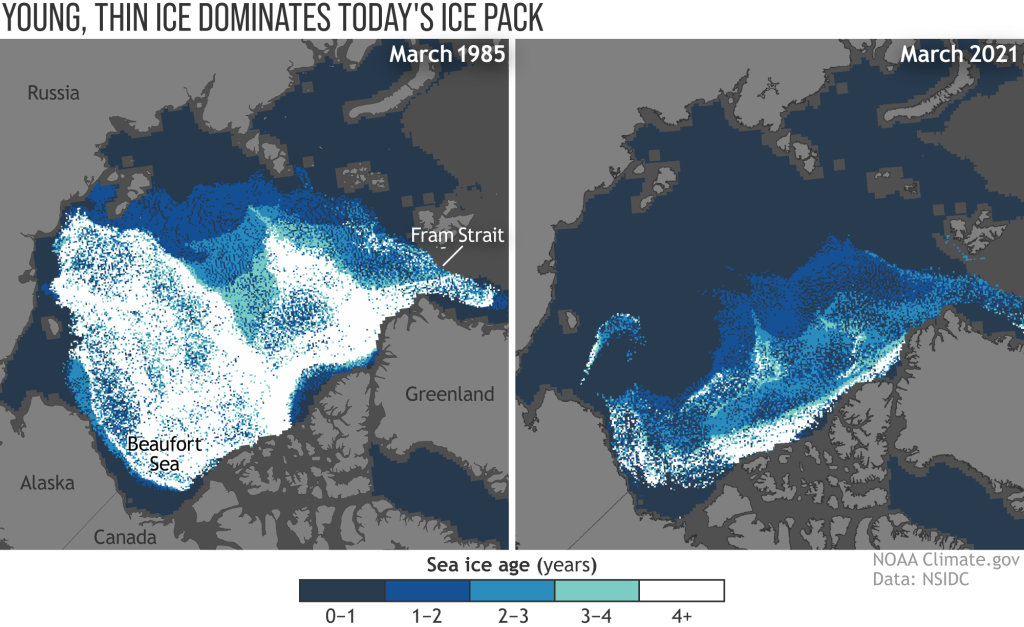

Maybe we are getting too used to records and superlatives. The minimum sea ice extent measured in September didn’t set a new record. But it was “significantly below the long-term average”. The amount of older, multiyear ice was only the second lowest since 1985. The average surface air temperature over the Arctic from October 2020 to September 2021 was only the 7th-warmest on record. The Arctic has already warmed so much that a year’s worth of data with figures way out of line with the long-term averages before we started to mess with the climate don’t jump out at us any more.

In fact, October to December 2020 was the warmest Arctic autumn on record, dating back to 1900. The snow-free-period across the Eurasian Arctic during summer 2020 was the longest since at least 1990. June 2021 snow cover in Arctic North America was below the long-term average for the 15th consecutive year. June snow cover in Arctic Europe has been below average 14 of the last 15 years. The Greenland ice sheet has lost mass almost every year since 1998. And this August, for the first time ever, it rained at the summit of that massive ice sheet.

The volume of post-winter sea ice in the Arctic Ocean in April 2021 was the lowest since records began in 2010. The amount of older, biologically important multiyear sea ice at the end of summer 2021 was the second-lowest since records began in 1985. The total extent of sea ice in September 2021 was the 12th lowest on record, with all 15 of the lowest minimum extents having occurred in the last 15 years.

“The substantial decline in Arctic ice extent since 1979 is one of the most iconic indicators of climate change”, the report’s authors comment. It has enabled shipping and other commercial and industrial activities to push deeper into the Arctic, in all seasons, “resulting in more garbage and debris collecting along the shore and more noise in the ocean, which can interfere with the ability of marine mammals to communicate”.

Some of the fastest rates of ocean acidification around the world have been observed in the Arctic Ocean. Two recent studies indicate a high occurrence of severe dissolution of shells in natural populations of sea snails, an important forage species, in the Bering Sea and Amundsen Gulf.

NOAA Administrator Rick Spinrad sums up the results:

“The Arctic Report Card continues to show how the impacts of human-caused climate change are propelling the Arctic region into a dramatically different state than it was in just a few decades ago. The trends are alarming and undeniable. We face a decisive moment. We must take action to confront the climate crisis.”

Each line represents one year of #Arctic sea ice thickness from 1979 [dark blue] to 2020 [dark red]. This year is shown in yellow – now updated through November 2021

+ More visuals: https://t.co/uzWknWmNnX pic.twitter.com/SS27ow4hrD

— Zack Labe (@ZLabe) December 11, 2021

Alarming acceleration in the Antarctic

The latest news concerning the Antarctic, at the other end of the globe was, if possible, even more alarming.

What scientists are projecting will happen to the Thwaites Glacier in the next three to five years should be front page news everywhere today.

Short thread. pic.twitter.com/lU4syY01bt— Philip Boucher-Hayes (@boucherhayes) December 15, 2021

Scientists announced that the massive ice shelf holding in place the Thwaites Glacier, one of the fastest changing glaciers in Antarctica already contributing up to 4 % of global sea level rise, is fracturing in many places and in danger of breaking apart. The scientists compare what is happening to a crack in the windshield of a car:

“A slowly growing crack means the windshield is weak and a small bump to the car might cause the windshield to suddenly break apart into hundreds of panes of glass. We have mapped out weaker and stronger areas of the ice shelf and suggest a “zig-zag” pathway the fractures might take through the ice, ultimately leading to break up of the shelf in as little as 5 years, which result in more ice flowing off the continent “, they write.

5 years is a shocking figure. The floating ice shelf acts as a dam, slowing the flow of ice into the ocean. Its demise would mean the massive Thwaites Glacier, sometimes called the Doomsday Glacier, would flow into the ocean faster, increasing its contribution to sea level rise by up to 25%, ultimately more than half a metre.

Scientists also believe this could speed up the melting of other giant glaciers in Antarctica, ultimately resulting in a catastrophic global sea level rise of several metres.

Experts used to assume it would take centuries for Antarctica’s massive glaciers started to collapse. Now, it seems, the start could be just years away. And these change processes seem to be speeding up all the time.

Will we never learn?

So have the weather extremes and disasters of 2021 tipped the scales, convinced the world of the need for urgent action to cut greenhouse gas emissions and halt global warming? Beh Lih Yi sums it up in the headline of an article for the Thomson Reuters Foundation:

“In 2021, governments blew hot on 1.5C goal, colder on climate action”. The author says the disasters of the past year have convinced many more governments of the need to keep to the target of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Unfortunately, there is still a huge gap between the target and what is actually happening.

📈 415.95 ppm #CO2 in the atmosphere December 10, 2021 📈 Up from 413.95 ppm a year ago 📈 Mauna Loa Observatory @NOAA data & graphic: https://t.co/MZIEphYygh 📈 https://t.co/DpFGQoYEwb tracking: https://t.co/PTTkLiPGm2 🙏 View & share often 🙏 pic.twitter.com/gZVfahBub4

— CO2_Earth (@CO2_earth) December 11, 2021

Former IPCC chair Robert Watson told the Thomson Reuters Foundation that goal was “now harder to reach than ever before”. He warns that “the rhetoric is consistent with 1.5C, but the pledges are not.” Even the less ambitious global target of staying below 2C is in doubt, with global emissions on their present course. Climate Tracker comes up with a sobering 2.4°C, taking account of all the pledges and promises made so far.

Since COP26, China and India have told their mining firms to boost coal production to plug energy shortages, while President Joe Biden asked U.S. oil and gas companies to raise production to ease high prices, Watson pointed out.

The IEA has announced that the amount of electricity generated from coal is expected to hit an all-time high this year:

“Coal is the single largest source of global carbon emissions, and this year’s historically high level of coal power generation is a worrying sign of how far off track the world is in its efforts to put emissions into decline towards net zero,” Fatih Birol, the executive director of the IEA, said in a press release.

“Asia dominates the global coal market, with China and India accounting for two-thirds of overall demand. These two economies—dependent on coal and with a combined population of almost three billion people—hold the key to future coal demand,” Keisuke Sadamori, director of energy markets and security at the IEA, said. “The pledges to reach net zero emissions made by many countries, including China and India, should have very strong implications for coal, but these are not yet visible in our near-term forecast, reflecting the major gap between ambitions and action.”

Birol described the findings as a “sobering reality check of the government policies.”

Glasgow COP26 just handed out more homework

The UN Climate Conference in Glasgow in November failed to come up with the necessary pledges let alone concrete measures that would keep global warming below 1.5°C.

Climate policy expert Niklas Hohne of the Germany-based NewClimate Institute said that while more leaders had spoken out in favour of a 1.5C limit than 2C, the “discrepancy between the firmness and the reality of the 1.5C goal has widened in 2021“.

We know the world has already warmed by around 1.2°C. Here in Germany, the figure is already 1.6°C. The Arctic is warming at up to four times the global average.

Over the last several decades, the #Arctic is warming nearly four times faster than the global average… pic.twitter.com/8xKKaSvUU6

— Zack Labe (@ZLabe) December 8, 2021

In spite of all the catastrophes the world has seen over the past year, the change we urgently need is not forthcoming – at least not fast enough. In spite of all the lip service: the fundamental will to change our lifestyles, societies and economies starting right now to save the world for future generations is sadly absent.

In January 2021, what was described as the biggest ever opinion poll on climate change found that two-thirds of people think it is a “global emergency”.

The UN Development Programme (UNDP) had questioned 1.2 million people in 50 countries, many of them young. The survey showed people across the world wanted their politicians to take the major action necessary to halt climate change, even when climate action required significant changes in their own country.

A survey carried out as part of a study into “eco-anxiety” by the University of York and Global Future think tank ahead of COP26 showed a majority of people believe climate change will have a more significant effect on humanity than will COVID-19. The poll revealed that overall, 78 percent of people reported some level of fear about climate change, with 41 percent reporting being very much or extremely fearful.

Yet an international poll conducted in autumn 2021 suggests that although almost 80% percent of those from around the world surveyed said they were concerned about the climate crisis, almost half — 46 percent — said they didn’t feel much of a need to change their own habits. They expected their governments to take action instead.

This time last year, I noted here on the Ice Blog that UNEP regarded the growing number of countries that have committed to achieving net-zero emissions goals by around mid-century as the most significant and encouraging development in terms of climate policy. The proof of the pudding, I wrote then, will be how – and how fast – they are turned into policy and action.

Sadly, as we approach the new year, I come to the conclusion that the pudding has been a disappointing flop.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Nunavut, Canada breaks 47 daily temperature records in 1st 6 days of October, CBC News

Finland: Temperatures headed toward -40C in Finnish Lapland, Yle News

Greenland: Arctic Report Card 2021 – Sea ice changes, rain on Greenland ice sheet among dramatic changes in North, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Blog: Radical Arctic warming – rain, rain, here to stay?, Marc Lanteigne

Russia: WMO confirms 38 C Arctic temperature record in Russia, Eye on the Arctic

Sweden: January temperatures about 10°C above normal in parts of northern Sweden, says weather service, Radio Sweden