Nunavut education department launches school violence data tracking system

993 violent incidents reported in 2021-2022 school year

Nunavut’s education department has launched its long-awaited school violence data tracking system.

The new database, some nine years in the making, will standardize school violence tracking across the territory and give policymakers a more accurate picture of the issue to help allocate resources to address it.

Previously, what violence tracking the department did was inconsistent and sometimes inaccurate, it said. A CBC News investigation last year, in which CBC created a spreadsheet to be sent out to all schools to fill out, marked the first time the department had compiled statistics on school violence.

The new system is an online reporting tool, accessible through the Nunavut Teachers Association website and the department of education’s health and safety site, will allow educators, staff and students to report incidents in less than five minutes.

All reports will go into a central database which only certain government or teaching association staff will be able to access. The department is aiming to publish its first statistics in April or May 2023.

“I think this is a huge development. I think it’s incredibly encouraging,” said Jane Bates, Nunavut’s children and youth representative, who has long called for better tracking on the issue.

“The only thing I would say is a tracking system is only effective if the system gets used. So it relies upon the people to input the data. You can’t get data from a tracking system if you’re not using it, and using it consistently across the board.”

“This is big,” added Nunavut Teachers Association president Justin Matchett.

“I think it’s really going to benefit our communities now that we can actually collect data, see where it is, and see where the highest instances of violence are happening in our schools and try and lobby the government to support those communities that need it the most.”

‘We need to figure this out’

Department officials said the new system was needed because there had been no reliable system in place to collect and track data across all communities, nor did officials have data on hand to have a clear understanding of concerns from within their schools.

“The goal of it is so that we have a database that will help us make and take very intentional steps, even though we’ve already done so,” said deputy minister of education Rebecca Hainnu, maintaining the department has always tracked violence, just not in a manner in which the data could be extracted and analyzed. Things changed once Bates’s office and CBC News raised questions on it, Hainnu said.

“We didn’t think that way. We didn’t act that way. We didn’t capture it as having data to publish. The department wasn’t collecting data for the sake of reporting out to the public,” Hainnu added.

“What the department was doing was it had its head down, working on solutions and deploying funds and mechanisms for District Education Authorities to empower them so that they could have positive schools in those communities.”

Other measures Hainnu highlighted in recent years include hiring more Ilinniarvimmi Inuusilirijiit (also known as school community counsellors), increasing the number of schools with mental health services, and having a “learning coach” in each school to try and alleviate language barriers.

And while the lack of clinical mental health support for students has previously been raised by Bates’s office and by educators, Hainnu said it’s about having a repertoire of both cultural and clinic support systems for students.

“We are increasing their chances of success — their chances of feeling better after not feeling well. Whether it’s mental health, whether it’s lack of finances, whether it’s the housing situation, we need to put in the support systems for every student,” she said.

“We need to figure this out.”

Rate of violence is ‘very small’

Short of having a more formalized system in place, the department has continued reporting statistics to Bates’s office since the first batch of numbers came to fruition in CBC’s investigation.

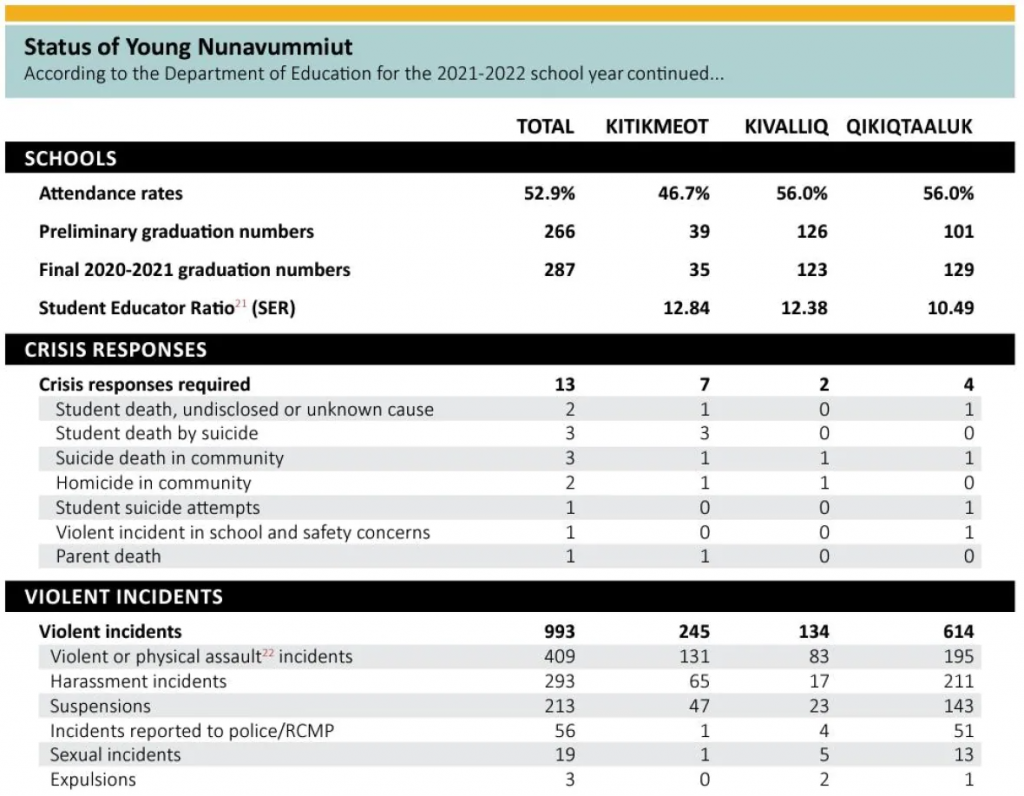

In Bates’ latest annual report, the department reported 993 violent incidents in the 2021-22 school year — notably, this is the first time in which there was no footnote indicating the numbers risked being inaccurate.

“Based on the 10,389 students and 993 incidents, the percentage of violent incidents is very small compared to other jurisdictions,” Hainnu said.

“The focus of violence in schools shouldn’t be interpreted [to mean] that we have violent students right across Nunavut only. It’s everywhere.”

Matchett, the president of Nunavut’s teachers union, also echoed the sentiment.

“I feel Nunavut’s kind of got this bad picture happening where if people research Nunavut they’re seeing that ‘Well I’m not going to go teach there, there’s so much violence happening,'” he said.

“I think we need to do a better job of identifying that not all of Nunavut has specific serious issues.”

If you’re Indigenous and experiencing emotional distress, call the First Nations and Inuit Hope for Wellness Help Line at 1-855-242-3310.

For help in Inuktitut, you can call the Kamatsiaqtut Help Line at 1-867-979-3333 or, toll-free from Nunavik or Nunavut, at 1-800-265-3333.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Post-secondary education offered in Nunavik, Quebec would be a game changer, says school board, Eye on the Arctic

Greenland: Nunavut children’s books translated for circulation in Greenland’s schools, Eye on the Arctic

Sweden: Can cross-border cooperation help decolonize Sami-language education, Eye on the Arctic