Could glass be answer to Giant Mine toxic legacy? Research is underway to find out

Arsenic can dissolve but glass cannot, says tech company

Turning dust into glass could be the key to a permanent solution for a poisonous legacy buried at Yellowknife’s Giant Mine.

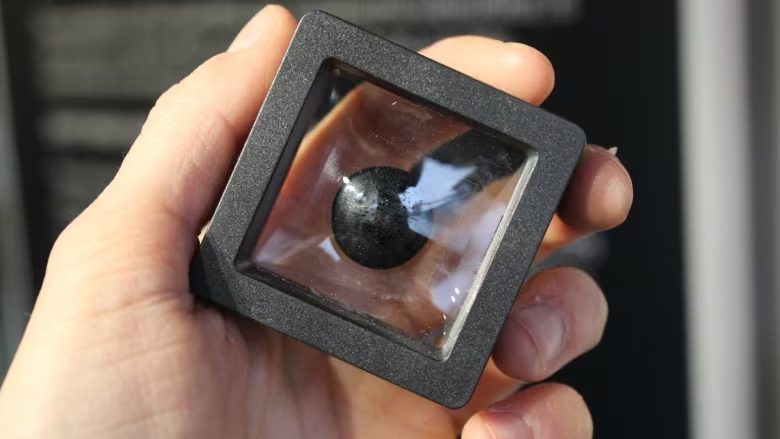

The Giant Mine Oversight Board (GMOB) is working with a technology company based in Montreal to incorporate samples of the 237,000 tonnes of highly toxic arsenic trioxide dust buried at the former gold mine into glass.

“Arsenic is a very soluble metal,” said Jean-Phillipe Mai, the president and CEO of Dundee Sustainable Technologies, the company contracted to do the work. “The real benefit of using glass is … it’s insoluble and can withstand and be stable over long periods of time.”

Marc Lange, a director of the oversight board, said it commissioned three types of glass to be made, containing arsenic trioxide at rates of five, 10 and 15 per cent. The pieces of glass they’ve received are going through tests that replicate the conditions of being stored below or above ground.

“Imagine putting them below ground. They might break,” he explained. “So the scientists are crushing them and … running water, for example over those samples repeatedly to simulate 100 years of the waste being below ground.”

Lange said the water and crushed glass are then studied to see if anything is coming out of the material and why. But what they’ve found out so far hasn’t been released to the public.

In an email to CBC News, Ben Nind, the executive director of the GMOB, said the board would not release that kind of information until testing is done and the results are peer-reviewed. Nind, who declined to do an interview with CBC News, said he expects the first results of the research projects to be published this year or in 2024.

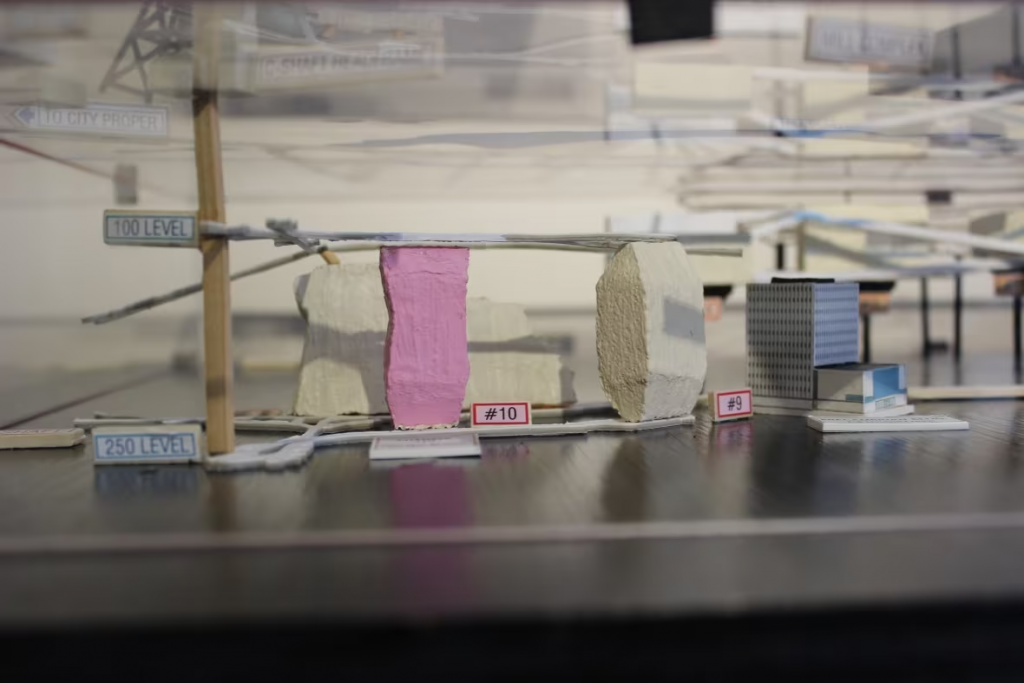

If all the arsenic trioxide dust at Giant Mine were to be turned into glass — the sheer volume of it would be enormous. Mai said glass containing 20 per cent arsenic would be five times bigger than the volume of arsenic — which works out to nearly 1.2 million tonnes.

The amount of arsenic trioxide is huge already. Models of the mine at the GMOB’s office compare one of the mine’s 14 chambers containing the dust to the 11-storey Precambrian Building in downtown Yellowknife.

$270K spent on research in 2022

Turning arsenic into glass is one of a few research projects the GMOB is investigating to eventually transform the killer dust. Although it was recently announced the overall budget for Giant Mine’s remediation has ballooned to $4.38M — the current solution of freezing the dust below ground is not considered to be a permanent solution.

GMOB was established in 2015 with two purposes in mind: oversee the remediation of the Giant Mine site and manage a research program searching for a permanent solution for the toxic dust. They also accept unsolicited proposals and have received six as of early December — one that Lange said was being considered for research funding.

The GMOB spent $270,000 on researching a permanent solution for the arsenic waste in 2022. Making it less toxic, trapping it in cement, and figuring out what exactly it’s all made of are three other areas of research the GMOB has been looking into.

The latter, said Lange, is an important component to all of the research that’s going on.

Lange said the key finding is that arsenic waste stored below Giant Mine is not pure arsenic trioxide. Its composition varies between chambers because of the different gold mining processes that were used.

“It matters in the next step, as we look at transforming this waste. If you have this unknown sort of powder, it’s really difficult to transform it in a predictable way,” he said, noting that samples from Giant Mine have been behaving “very differently” than laboratory-grade arsenic trioxide.

What about extraction?

All of the seven projects the GMOB is currently involved in have to do with transforming the arsenic waste into something else. Lange said that research focus stems from public feedback.

“There [were] a lot of questions around how do you make the arsenic less toxic, or make it sort of go away,” he said. But, Lange said, that doesn’t mean two other areas of research — how to extract the waste and what to do with residual traces that might be left behind in the chambers — are being ignored.

“The idea of bringing this very dangerous powder from deep below ground and bringing it up so that you can treat it … is actually pretty complex,” he said. “We don’t have a solution, the government doesn’t have a solution for extracting safely.”

Lange said the GMOB has commissioned a study to look at different types of extraction methods.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Canada, territories need to better communicate on Giant Mine cleanup, says review board, CBC News

Norway: Norway to press Russia for action on Arctic smelter pollution, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: New Finnish technology to slash nickel mining pollution in northwestern Russia, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Many towns in Sweden seek funds to clean up polluted sites, Radio Sweden

United States: America’s most toxic site is in the Alaskan Arctic, Cryopolitics Blog