Blog: Don’t be fooled – we can and we must limit temperature rise to 1.5°C

“It’s too late to stop Antarctic ice melt.” But “the Greenland ice sheet might be more resistant to warming than we thought”, according to various recent studies. So should we stop worrying? Or give up on climate action? As we speed towards this year’s UN Climate Conference COP28, to be held in – of all places – oil-rich Dubai, while wars in the Middle East and in Ukraine are distracting attention from the planet-threatening climate crisis, what we need is not complacency or resignation but a heightened sense of urgency.

The planet’s ice and other aspects of climate change are getting a lot of media attention right now. And rightly so. This was to be a key year for climate action

This decade is crunch-time. And the storms, floods, fires and record air and ocean temperatures we have been seeing around the globe are showing us climate change in action. We are running out of time. The question is how headlines suggesting either it could be too late – or that we still have plenty of time – will affect public behaviour and this year’s climate negotiations, coming up very soon.

Too late to stop Antarctic ice melt?

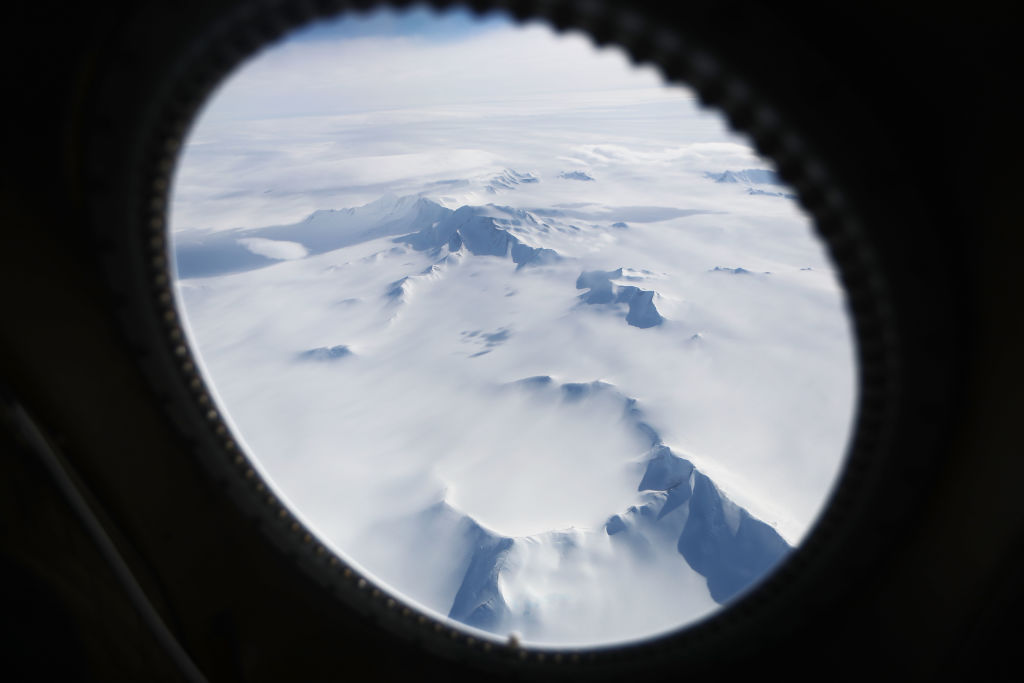

The Antarctic is featuring prominently in the media. We are catching up on a lot of lost time. Easier accessibility and advances in satellite and other monitoring technology as well as the picturesque, media-friendly landscape with ice, snow and penguins have attracted attention to stories about the “bastion of cold” in the far south of the planet. Alas, the news is rarely good. A study published last week has the potential to depress us all and be misused as an excuse to abandon climate action and the energy revolution.

Kaitlin Naughton from British Antarctic Survey (BAS) , lead author of “Unavoidable future increase in West Antarctic ice-shelf melting over the twenty-first century”, published in Nature Climate Change on October 23, sums up the findings in The Conversation: “The rate at which the warming Southern Ocean melts the West Antarctic ice sheet will speed up rapidly over the course of this century, regardless of how much emissions fall in coming decades, our new research suggests. This ocean-driven melting is expected to increase sea-level rise, with consequences for coastal communities around the world. “

The Antarctic ice sheet is the world’s largest volume of land-based ice. Coastal ice shelves are the floating edges of this ice sheet which stabilise the glaciers behind them. The ocean melts these ice shelves from below, and if melting increases and an ice shelf thins, the speed at which these glaciers discharge fresh water into the ocean increases and sea levels rise, Naughton explains.

In West Antarctica, the area most vulnerable to climate warming, this process has been underway for decades. Ice shelves are thinning, glaciers are flowing faster towards the ocean and the ice sheet is shrinking. Naughton and her colleagues chose to model the “most vulnerable sector of the ice sheet”, the Amundsen Sea. Using the UK’s national supercomputer ARCHER2 , the team ran many different simulations of the 21st century, “totalling over 4,000 years of ocean warming and ice-shelf melting in the Amundsen Sea.”

They considered different scenarios for future burning of fossil fuels, from the best-case scenario where global warming is limited to 1.5°C in line with the Paris Agreement, to the worst, in which “coal, oil and gas use is uncontrolled.” They also took account of the influence of natural variations in the climate, such as El Niño.

“The results are worrying”, Naughton concludes. “In all simulations there is a rapid increase over the course of this century in the rate of ocean warming and ice-shelf melting. Even the best-case scenario in which warming halts at 1.5°C, something that is considered ambitious by many experts, entails a threefold increase in the historical rate of warming and melting.”

Constructive reporting in crisis?

As the lead author discusses in The Conversation, this makes it hard to bring across a positive message:

“How do you tell a bad news story? The conventional wisdom is that you’re supposed to give people hope: to say that there’s a disaster behind one door, but we can avoid it if only we choose a different one. What do you do when your science tells you that all doors lead to the same disaster?”

An extremely sobering question, especially coming from a scientist at the cutting edge of research. Naughton suggests we have to shift our attention to the longer term:

“The future will not end in 2100, even if most people reading this will no longer be around. Our simulations of the 1.5°C scenario show ice-shelf melting starting to plateau by the end of the century, suggesting that further changes in the 22nd century and beyond may still be preventable. Reducing sea-level rise after 2100, or even slowing it down, could save many coastal cities.”

But most of us humans tend to live in the here-and-now and are unwilling to look beyond, and make sacrifices in the interests of future generations. The challenge is to avoid resignation and make sure worrying findings like these do not become an excuse for inaction and business as usual.

Should we stop worrying about Greenland’s ice sheet?

Another recent study published in the scientific journal Nature on October 18 highlights the danger of the opposite extreme:

“The Greenland ice sheet is likely to be more resistant to global warming than previously thought”, the study finds. An international team of scientists led by Nils Bochow from UiT The Arctic University of Norway and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research found that “even if critical temperature thresholds are temporarily crossed by up to 6.5 degrees Celsius until 2100, a possible tipping of the ice sheet and therefore drastic sea level rise over hundreds of thousands of years could be prevented. To achieve this, measures to reduce greenhouse gases would have to be taken as quickly as possible following the critical rise in temperature, so that the temperature can be stabilized at no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels in the long term.”

6.5°C? Did I read right? So – the Greenland ice might not melt after all – aha! We still have time to overshoot by an amazing amount? Great material for those who would like to prolong the exploitation and burning of fossil fuels and put off the energy transition for as long as possible. The risk of the findings being misused by those who would like to play down the risk of exceeding the 1.5°C limit is worrying.

In fact the authors are keen to stress that this should not be the conclusion and that we still need to keep temperature rise down:

”We found that the ice sheet reacts so slowly to human-made warming that reversing the current warming trend by cutting greenhouse gas emissions within centuries may prevent it from tipping. Yet, also just temporarily overshooting the temperature thresholds can still lead to a peak in sea level rise of more than a metre in our simulations”, said co-author Niklas Boers from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and the Technical University of Munich, Germany.

The authors caution that their results are based on limited ice sheet modelling that “disregards how the concerted global climate change influences the Arctic climate apart from temperatures and precipitation”. In other words, we only have one part of the story here. They stress that essentially all other sub-elements of the climate system react faster to global warming than an ice sheet. These include rainforests, wind and precipitation patterns, or ocean current systems, which all change or even commit to abrupt, irreversible changes on significantly shorter time scales, leading to much shorter windows of opportunity to avoid tipping.

“And even when avoiding a large-scale tipping of the Greenland ice sheet, temporary sea-level rise can be substantial. The higher temperatures rise, the more difficult it will be to bring them down to safe levels in the long term. This is why we need to act fast and keep global mean temperatures below 1.5 degrees Celsius”, concludes Niklas Boers.

“The Greenland ice sheet is just a small part of the picture and there are many other negative consequences related to human made climate change that we might face if we don’t act in time.”

There we have it. But only if we look into the whole story.

Bringing the latest science together

I was recently in the Norwegian capital Oslo for some meetings with scientists and colleagues from the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative (ICCI). I have been doing some work with the organisation, which publishes the annual “State of the Cryosphere” Report, with this year’s study due to be released shortly, ahead of COP28. What those scientists had to say, based on the very latest research findings, left me in absolutely no doubt that 1.5°C is the absolute upper limit to avert further damage to the ice- and snow-covered regions of our planet, and resulting devastating impacts worldwide.

Ice sheets and glaciers: Thresholds and Feedback

At a public lecture event at Oslo University organised by ICCI and WWF, three leading experts presented an overview of the latest science on all matters icy. Chris Stokes from the University of Durham is one of the world’s leading scientists on glaciers and ice sheets:

“I think one of the worrying things – and one of the worrying messages to policymakers – is that every time we get new measurements, new data, new observations, it seems to be showing that things are worse than before, maybe just a few years ago. And this, I think, is the same for both Greenland and Antarctica,” he told the audience.

Looking at past climate provides essential insights that help us understand what’s happening now and what is likely to occur in the future, says Stokes:

“There’s a really important lesson from the past that sea level rise from ice sheets can be much, much quicker than we’re experiencing at present. I think that fact sometimes gets lost when we’re talking about millimetres per year.”

The message from the past is not encouraging:

“We know in the past, for example, that when sea level rose, particularly around about 14,500 years ago, there were jumps. And some of these jumps were so rapid that we could have seen rates of sea level rise approaching four metres per century”.

Now that is a scary thought.

“It is really worrying”, Stokes says, and this is because there are a number of self-sustaining reinforcing feedback mechanisms that take place within ice sheets. They do not respond linearly to climate forcing”, he explains. “There’ll be a point where there’s a slow response and then all of a sudden you pass a threshold and it becomes much more rapid.”

The ice expert is frightened by the fact that during his lifetime we have already added almost 100 ppm of CO2 to the atmosphere – as much as the amount associated with deglaciation in the past, the shift from a glacial to an inter-glacial period, which took around 10,000 years.

Unlikely hotspots

West Antarctica, as discussed above, is the area of Antarctica most subject to melting. Eastern Antarctica was long considered insensitive to climate warming. Perceptions here, too, are changing, says Stokes:

” I looked back in the literature: just maybe 30 years ago, people used to argue and point out from some of the very basic numerical modelling that it would take 16 degrees of warming before we saw a reaction from East Antarctica. And we now think that’s less than 2 degrees for some parts of East Antarctica. So again, the science is moving forward very rapidly here.”

The researchers have identified “hotspots”, especially in the Wilkes Land region.

“We have a mini West Antarctica located here in this part of East Antarctica. Mass loss here is now ten times higher than it was a decade ago. We know that the circumpolar deep water has warmed by around a degree to two degrees since the 1990s, and some of the work we recently did showed the grounding-line retreat for one of the glaciers here is actually comparable to the Thwaites glacier – the “Doomsday” glacier, which is well publicised.

“We’re starting to see some really worrying signs fom East Antarctica”, he told his engrossed Oslo audience, that we really need to keep an eye on.”

Acid oceans

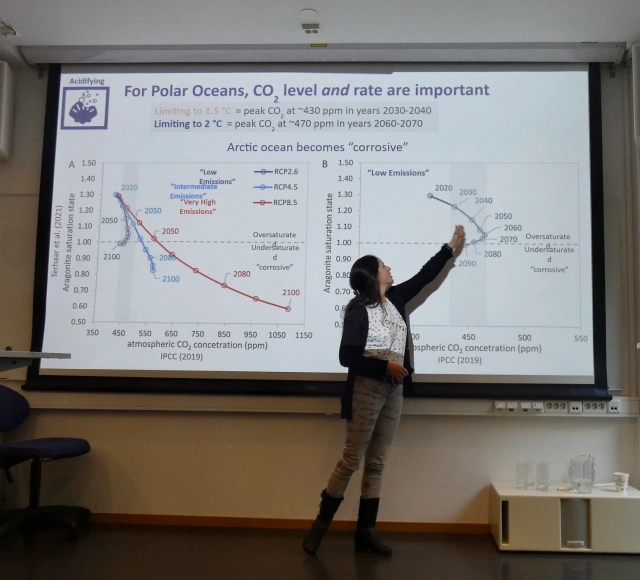

Sea level rise is not the only factor we have to worry about. Helen Findlay from Plymouth Marine Laboratory is a biological oceanographer and expert on climate impacts, especially ocean acidification through the increased concentration of CO2 in the world’s oceans.

“Polar oceans are far more sensitive to rising temperatures and CO2 than the global average, some changes are irreversible or very long-term in terms of warming and acidification, and significant damage will be felt at 2°C. 1.5°C will greatly limit that loss of ecosystems. But we’re actually already seeing a lot of these impacts at one degree and we need to act now,” she said in Oslo.

“When we focus in on the Arctic Ocean, nearly every projection into the future, from low emissions up to high emissions, will see us move into corrosive waters, corrosive conditions. Even in the low emissions scenarios, the majority of the water column are going to be experiencing these corrosive conditions and exposing organisms to those conditions. The problem with acidification, is that it’s essentially permanent. We’re talking about geological timescales for things to recover, tens of thousands of years. So if we were to stop emitting CO2 in the 2100s and just stayed at those levels, then the pH of the oceans, both the Arctic and the Southern Ocean, would not turn back to where they were before”.

When we look at these climate impacts, we tend to talk about global averages. The scientists speaking in Oslo reminded us that there will be huge regional differences. Whether we look at sea level rise, geo-hazards or ocean acidification, some regions will be hit much harder than others. Findlay has an impressive example from the latest planetary boundaries report. While it found that the boundary for ocean acidification “is close to being breached”, areas of the polar oceans have long crossed the line.

Geo-hazards and food insecurity

It’s not just the polar ice that is causing concern. Ugo Nanni from the University of Oslo is an expert on mountain glaciers. The past two summers saw a drastic decline in Europe’s alpine glaciers. Even in the icy Himalayas, melting ice and snow through our human-induced global warming are posing a huge threat. A study published earlier this year showed that unprecedented and largely irreversible changes to the Hindu Kush Himalayan cryosphere, driven by global temperature rises, threaten two billion people and are accelerating species extinction.

Nanni outlined the geo-hazards relating to ice and snow melt – landslides, avalanches, floods. He also stressed the global relevance of snow and ice for food and water. Not only do local communities depend on water from glaciers for drinking and agriculture – 16 percent of products produced using snow melt are traded globally, says Nanni. He too presented powerful evidence that the impacts of warming on the cryosphere will be much stronger if we go over 2 degrees.

Cryosphere and the UN climate negotiations

There is an increasing awareness that the cryosphere plays a huge and long underrated role in the future of our planet. To date, though, this has not been adequately reflected in the UN Climate talks. Alliances are working at various levels to bring this into the COP negotiations. At last year’s COP27 in Egypt, a group of 20 countries created the Ambition on Melting Ice (AMI) high-level group on Sea-level Rise and Mountain Water Resources (AMI) “to ensure that the irreversible and devastating global impacts of cryosphere loss are understood by political leaders and the public alike: not only within mountain and polar regions, but throughout the planet.” At the One Planet – Polar Summit in Paris in early November, France will join the group and lead a push to encourage more countries to join and increase awareness and pressure.

As far as protecting the planet’s ice and snow is concerned, the science delivers a clear message. 1.5°C is a red line that must not be crossed. Even the higher 2°C still technically allowed by the Paris Agreement would result in very drastic impacts.

There are signs of hope

On the positive side, the World Energy Outlook 2023 from the International Energy Agency (IAE) registers considerable progress in reducing emissions:

“The combination of growing momentum behind clean energy technologies and structural economic shifts around the world has major implications for fossil fuels, with peaks in global demand for coal, oil and natural gas all visible this decade – the first time this has happened in a WEO scenario based on today’s policy settings”, the report reads.

“In this scenario, the share of fossil fuels in global energy supply, which has been stuck for decades at around 80%, declines to 73% by 2030, with global energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions peaking by 2025.

Global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from energy use and industry could even peak as soon as this year, according to a Carbon Brief analysis of the IEA figures, partly due to what the outlook describes as the “legacy of the global energy crisis triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.”

These are signs of improvement. But the world is still not moving fast enough:

“As things stand, demand for fossil fuels is set to remain far too high to keep within reach the Paris Agreement goal of limiting the rise in average global temperatures to 1.5 °C”, according to the IEA.

“This risks not only worsening climate impacts after a year of record-breaking heat, but also undermining the security of the energy system, which was built for a cooler world with less extreme weather events. Bending the emissions curve onto a path consistent with 1.5 °C remains possible but very difficult. The costs of inaction could be enormous: despite the impressive clean energy growth based on today’s policy settings, global emissions would remain high enough to push up global average temperatures by around 2.4 °C this century, well above the key threshold set out in the Paris Agreement, “ the IEA concludes.

Tough times for discussing climate

That sets the bar very high for the negotiators in Dubai. Germany’s special envoy for climate action, former WRI climate lead and Greenpeace chief Jennifer Morgan has been warning that the increase in wars and conflicts, not least in the Middle East, could well distract attention for the need for urgent climate action. The world cannot afford that, she told German radio.

This year’s UN conference is to take stock of measures taken so far to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. There are fears that fossil fuel players will try to weaken the consensus that the 2°C upper limit must give way to 1.5°C.

If that happened, it would spell disaster for our icy regions – and the rest of the world. The impacts of melting glaciers, thawing permafrost, disappearing sea ice are impossible to miss – they are global and potentially devastating.

That means, whatever we hear in the media, whether it seems to be a “doom and gloom” story or a “nothing to worry about” message – we must not lose sight of the imperative: we have to reduce emissions and halt temperature rise – right now.

We have to be prepared to make changes to our lifestyles. The states and companies that are profiting from fossil fuels have got to stop. The idea that we’ve still got time – or that it’s too late to do anything anyhow – are what we do not need. There could hardly be more at stake.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Arctic Permafrost Atlas offers insights into the North’s changing landscape, Eye on the Arctic

Greenland: Arctic ice melt could put 1.5 million UK properties at flooding risk: report, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Polar heat record. July average above 10°C, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: High risk of wildfires in many parts of Sweden, including North, Radio Sweden

United States: Bursting ice dam in Alaska highlights risks of glacial flooding around the globe, The Associated Press