Promoting Indigenous Voices: Greenland writers host summit on literature

In mid-September, about 60 authors, cultural leaders, and scientists gathered in Nuuk, Greenland, for a summit aimed at promoting and translating literature written in northern Indigenous languages. The event, held from September 19 to 22, brought together participants from various northern communities to explore how their written works could gain more recognition on the global stage.

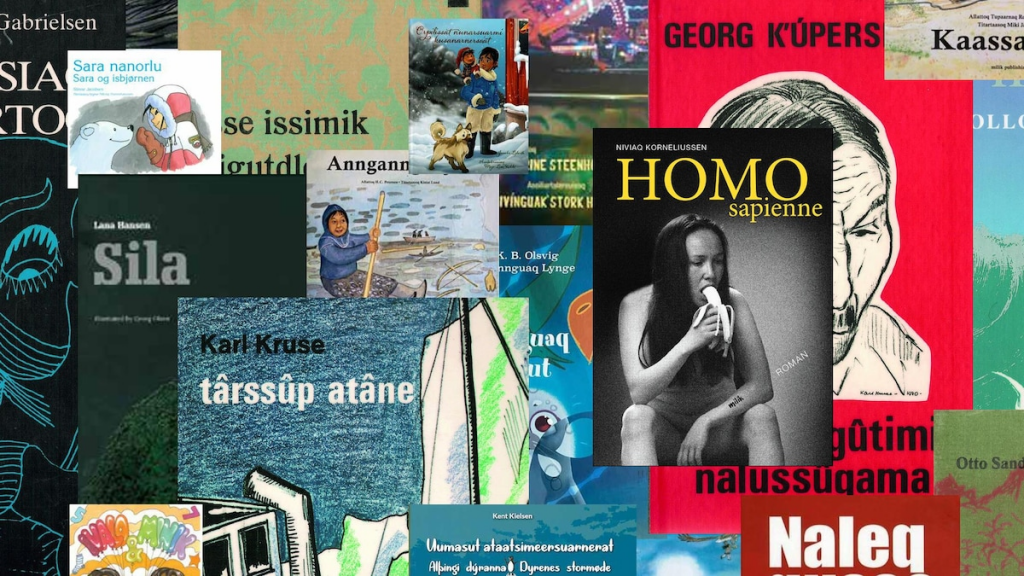

The summit was organized by the Greenland Writers Association, with an aim to discuss strategies for increasing the visibility of literature written in languages like Greenlandic, Sami, and Inupiaq.

“Many of these communities have few members, and their languages are spoken by even fewer people,” said Juaaka Lyberth, an award-winning author and cultural figure and the president of the association.

“If we want to preserve our culture, we need to write in our own language first. It’s important that small [northern] communities work together, or else we will be overwhelmed by the English language.”

With Greenland’s population at just over 56,000, Lyberth said that sharing Greenlandic literature internationally is crucial to its survival.

“Our goal would be to eventually publish not just 25 or 30 books a year, but closer to 300,” he said.

Links with Quebec university

Daniel Chartier, a professor and director of the International Laboratory for Research on the Imaginary of the North, Winter, and the Arctic at the Université du Québec à Montréal, was one of the conference speakers.

He said the lab’s partnership with the Greenland Writers Association will help promote translations of Greenlandic works into other languages, including French, as a way to broaden their reach beyond Danish.

The Quebec cultural sector has developed expertise in exporting local literature while also defending it, which could serve as a model for Greenlandic writers, Chartier said.

“Greenlanders see French as a gateway to the world, a way to break free from the [cultural] grip of Denmark,” he said.

Despite growing interest in Greenlandic literature—such as the success of author Niviaq Korneliussen—Lyberth noted that the number of books published in Greenland has not significantly increased in the past decade. He hopes to eventually see hundreds of titles published in the country, not just a few dozen each year.

However, translation of works remains a major challenge for Indigenous languages.

In Greenland for example, most works must first be translated into Danish before being adapted into other languages, increasing costs and limiting exposure, Lyberth said.

But Lyberth and Chartier say sharing Indigenous stories is vital for cultural preservation and they believe solutions can be found.

“We must take the time to do things right, but we must move forward to preserve our unique stories,” Lyberth said.

-Translated and adapted from a text by Jean-François Villeneuve at Radio-Canada’s Espaces autochtones

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Publisher in Arctic Canada putting Inuit-language books online amidst COVID-19 closures, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Budget cuts threaten international Sámi language cooperation, Yle News

Greenland: Nunavut children’s books translated for circulation in Greenland’s schools, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Walt Disney Animation Studios to release Saami-language version of “Frozen 2”, Eye on the Arctic

Sweden: Can cross-border cooperation decolonize Sami language education?, Eye on the Arctic

United States: Inuit leaders applaud UN move to designate International Decade of Indigenous Languages, Eye on the Arctic