35,000-year-old sabre-toothed kitten found preserved in Arctic Russia

A sabre-toothed kitten more than 35,000 years old has been found preserved in the Siberian permafrost, with the scientists behind the discovery saying it allows researchers to study the appearance of an extinct mammal with no modern counterpart for the first time.

“The discovery of H. latidens mummy in Yakutia radically expands the understanding of distribution of the genus and confirms its presence in the Late Pleistocene of Asia,” the researchers said in their paper published this month in the journal Scientific Reports.

“Thus, for the first time in the history of paleontological research, the external appearance of an extinct mammal that has no analogues in the modern fauna has been studied directly.”

The find was made in Arctic Russia in 2020 in Badyarikhskoe, a locality in Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) in Siberia in the permafrost.

First time species has been discovered in Asia

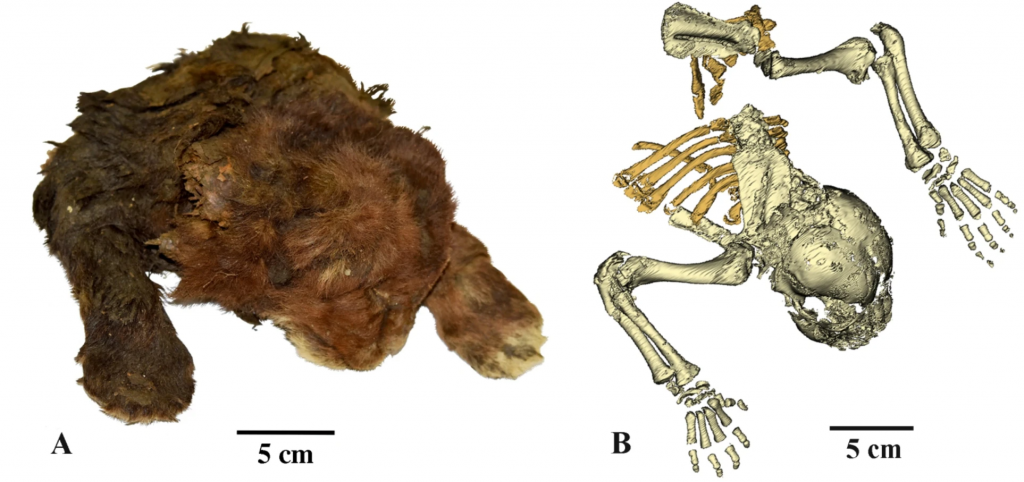

The mummified remains included the head, partial pelvic bones, and the femur and shin bones.

These were found in the ice, along with the front part of the cub’s body. Remarkably, the body was covered with 20-30 cm of brown fur described by the scientists as “short, thick, soft and dark brown.”

Scientists have determined that the cub was around three weeks old when it died, and they believe it belonged to Homotherium latidens, an extinct species of saber-toothed cat.

They say the finding is significant because it’s the second time Homotherium latidens has been identified in the Late Pleistocene of Eurasia and the first time it’s been discovered in Asia.

Cold-adapted features

The paper says the animal had several features that made it well-adapted to freezing temperatures including a muscular neck, long forelimbs and rounded paws.

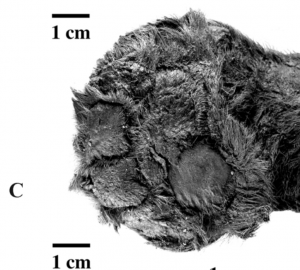

“The wide paw, the subsquare shape of its pads, and the absence of a carpal pad are adaptations to walking in snow and low temperatures,” the researchers said.

“The small, low auricles and absence of the carpal pad in Badyarikha Homotherium contrast with the taller auricles and normally developed pads in the lion cub. All these features can be interpreted as adaptations to living in cold climate.”

In addition to studying the cub’s fur, facial features, and the structure of its mouth, ears, and paws, the discovery also confirms that the animal lived in Late Pleistocene Asia, giving scientists fresh insights into its range, the researchers said.

Comments, tips or story ideas? Contact Eilís at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Indigenous oral history gives archeologists insight into early human life, CBC News

Finland: Finnish Heritage Agency scouring countryside for ancient monuments, Yle News

Iceland: Horses buried with Icelandic Viking nobles were male, ancient DNA shows, CBC News

Russia: Canadian researchers count on Siberian reindeer herders to solve archaeological mystery, Radio Canada International

United States: Historic buildings crumbling in Anchorage, Alaska face an uncertain future, CBC New