Indigenous oral history gives archeologists insight into early human life

University of Alaska archeologists are employing Indigenous oral history to gain more insight into what human life was like thousands of years ago.

Their research is centred on the Swan Point archeological site near Delta Junction, Alaska, about 350 kilometres west of the Yukon border.

The site dates back 14,200 years. It’s the oldest evidence of human life in Alaska, and among the oldest evidence of settlements in what is now North America.

It’s included in the area scientists call Beringia, which stretched from the MacKenzie River across the Bering Strait to eastern Russia.

Back then, sea levels were lower and there was a land bridge connecting Alaska and Siberia.

“We have several [Indigenous] place names around what would have been the northern shore of glacial Lake Atna that seem to describe the ancient glacial lake landscape, which is very interesting to us,” said Gerard Smith, a PhD candidate in the anthropology department at University of Alaska at Fairbanks.

Smith made a Skype presentation this past weekend at the Beringia Centre in Whitehorse as part of the Long Ago Yukon speaker series.

2,000-year-old home

The Swan Point site was discovered in 1993 and has been continually excavated since. It seems to have been occupied at various stages.

Two thousand years ago, it was home to what is now the Tanana people. Now their oral stories are shedding light on how people lived.

“They are not just stories, they are conveying very important information about the social life, the political and economic life, throughout the region,” Smith said.

He said the Indigenous stories weren’t abstract fairy tales that were passed down from parent to children, but stories about how to survive and how to do well.

“They tell you what you should do, how you should live your life successfully and how to succeed in the landscape around you,” said Smith.

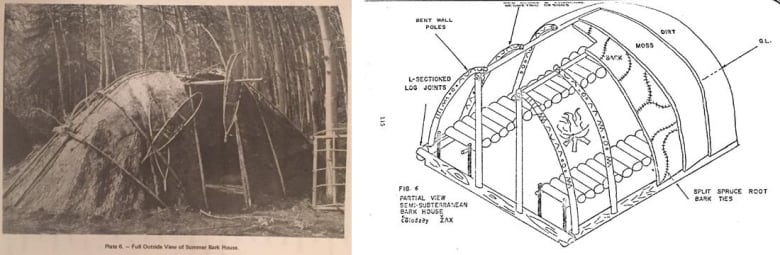

One of the most recent finds at Swan Point is a pit house.

One or two main houses are believed to have been reserved for the leaders of the village.

“This was a semi-subterranean house where people dug them into the ground and put a lot of wood and leather and moss on top of them to insulate them well,” Smith said.

A small footprint has also been found preserved in the house. Archeologists think it probably belongs to a nine-year-old girl who was wearing moccasins.

Kinship networks spanned Alaska-Yukon border

Christian Thomas, special projects archeologist for Yukon government, said one of the oldest sites in the Yukon is the Little John site near Beaver Creek (near the Alaska border), and that it’s probably around the same age as the Swan Point pit house. The people who occupied both sites likely shared much in common.

“In pre-colonial times, the kinship networks that existed spanned the Alaska-Yukon border. That’s a recent border that didn’t exist back in the day, so for the modern First Nations of the Yukon, their kin were the First Nations of Alaska,” Thomas said.

But the Swan Point site ultimately dates much further back than 2,000 years.

About 14,500 years ago, the North’s climate began to shift from a cold, glacial state to a warmer, interglacial state, before it then shifted back to near-glacial conditions.

That’s when the first people are thought to have crossed the land bridge from Siberia.

Smith is also attempting to envision the changes that have occurred since then, and what those early travelers would have encountered.

“It looks like the first people that came across the mountains encountered a lot of stagnant ice, a lot of glaciers, and then a couple of very massive glacial lakes, that [were] dammed to the south,” Smith said.

He said Lake Atna, which no longer exists, was half the size of Lake Ontario, one of the Great Lakes.

It’s not clear what happened to the very first people.

It’s theorized that as the glaciers retreated, they migrated further down the Pacific coast, eventually spreading throughout North America.

But that’s a matter of debate, as sites in what is now the US southwest have little in common with sites in the North, leading some scientists to speculate that a separate wave of people from South America may have been the first to populate the continent.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Glacier melt in Arctic Canada exposes plants frozen under ice for 40,000 years, CBC News

Norway: Climate change is driving micro-algae blooms into High Arctic and may affect food chains, says study, Eye on the Arctic

Russia: Russian researchers applaud construction of Arctic station, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: New map shows what Bering land bridge looked like 18,000 years ago, CBC News