Finnish Christmas traditions explained

The Christmas season is all about holiday traditions, from decorating the tree to prepping the big meal and waiting for Santa to arrive. But an authentic and uniquely Finnish Christmas also has its own markers and traditions, putting their own unique spin on the holidays.

“Even if the origins of a tradition can be traced elsewhere, the way we adapt something makes it uniquely ours,” says Finnish Literature Society archivist Juha Nirkko.

Starting with the man, the myth, the legend.

From Yulegoat to Joulupukki

Everyone knows Santa. Most people are aware that the inspiration for Father Christmas is St. Nicolas, a benevolent bishop from what is now Turkey. Many are even familiar with how the red-coated iteration of the kind, portly man who brings children gifts on Christmas can be attributed to American beverage giant Coca Cola.

Fewer people, however, may be familiar with Santa’s Finnish roots. (No, not his secret workshop in Korvatunturi, which we will get to in a minute.)

The image used by Coca Cola in their first Santa-driven Christmas campaign in 1931 was drawn by Haddon Sundblom, a second-generation Finn, whose family was from Åland. Between 1931 and 1964, Sundblom created over 40 images of Santa for Coca Cola, and is credited for creating the image we now associate with Santa Claus.

Finland, like most western countries, has embraced Santa wholeheartedly, but long before the charitable St. Nicholas made his way into Finnish households, he was preceded by joulupukki, or nuuttipukki, an evil spirit in the shape of a goat, that demanded gifts and leftover foods on St Knut’s Day (January 13) in exchange for crops and fertility. To this day in Southwest Finland, on the day many Nordic countries mark the end of the holiday season, men dressed in fur jackets, birch bark masks and horns go door to door, and if they don’t get what they want, they will scare the children.

“This tradition, of a man dressed up as something frightening, going from door to door in search of a bribe to make the coming year prosperous, has been part of kekri, Christmas and St, Knut’s, for a long time,” says Nirkko. “In Finland, as the tradition evolved, Santa came dressed in a fur coat and before he handed out a single gift, his intention was to scare kids.”

So, how did we go from a grumpy trick-or-treating goat to the much kinder Father Christmas living in Korvatunturi? Yle radio host Markus Rautio played a part in the Finnish appropriation of an international icon.

When Rautio, known to listeners as “Uncle Markus” declared on air in 1927 that Santa’s workshop was located in Lapland’s Korvatunturi, Finns immediately took to the tale. If you knew anything about topography, it only made sense: There is nothing for reindeer to eat in the North Pole, but in Lapland they roam free. Moving Santa’s visiting centre to Rovaniemi, however, was a more financially driven decision—one that annually drives half a million visitors to the Arctic Circle.

From harvest decorations to tannenbaum

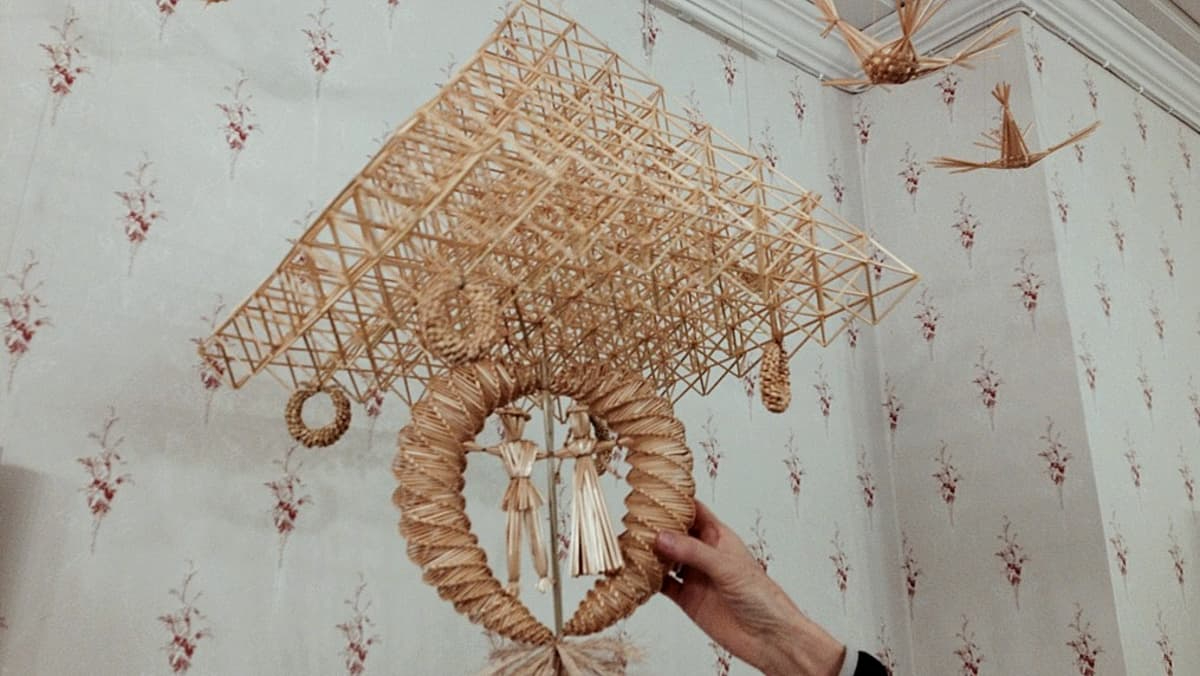

With its roots in kekri, the festival that marked the end of the yearly harvest, it is only natural that many of these Finnish holiday traditions have been integrated with modern-day Christmas. Traditional decorations are still often made from straw, like the typically Finnish decoration, himmeli, a hanging mobile meant to evoke heaven, which is hung above the dinner table over the holidays. Another decoration staple in the Finnish home is a heart-shaped wreath made from straw.

Before the introduction of the Christmas tree, which made its way to Finland in the middle of the 1800s from Germany, through the Baltics, the way families transitioned from daily life to holy days was by covering their floors with straw. The straw served many a purpose: It kept the draft from emerging between the floorboards and allowed for a place where children could play and houseguests could sleep.

“As people’s way of living changed, along with our standards of cleanliness, the straw became more of a fire hazard and a hassle. Over time, it was replaced by the Christmas tree,” says Nirkko.

How the pine tree made its way into Finnish homes and hearts is an interesting anecdote in itself.

“About a hundred years ago when Finland became independent and established compulsory education, there was an education guide with instructions pertaining to the annual tree celebration. Every school had an identical holiday party, with a Christmas tree, decorations, cards and gifts. Even Santa attended this party, which became the great unifier for how Christmas was meant to be celebrated,” Nirkko explains.

Christmas Christianity

Throughout December, the predominantly Lutheran—yet mostly secular—Finns discover their spirituality—or at the very least, their sentimentality. Approximately a million people, regardless of religious affiliation, go to church over the holidays, for joulukirkko (Christmas service), concerts and to contribute to the sea of candles across cemeteries on Christmas Eve.

“The lighting of candles on graves became a national tradition after the Second World War,” explains Nirkko. “There was a lot of grief in the country at the time, with so many fallen soldiers. That’s when visiting their graves became more frequent, and a tradition that has now lasted for decades.”

During the holiday season, churches are often packed for concerts where beloved Christmas hymns and carols are sung by choirs and congregants in equal measure. Some favorite Finnish Christmas carols include the melancholic Varpunen jouluaamuna (The sparrow on Christmas morning), Sylvian Joululaulu (Sylvia’s Christmas Song) written by Zacharias Topelius, Näin sydämeeni joulun teen (Making Room for Christmas in My Heart) by Kassu Halonen and Vexi Salmi and Tulkoon joulu (May Christmas Arrive) by Pekka Simojoki.

“These concerts add to the ambiance of Christmas, even if you’re not particularly religious,” Nirkko adds.

The Christmas Feast

Unlike many other countries where the big feast takes place on Christmas Day (December 25), the most celebratory meals are enjoyed on Christmas Eve in Finland.

The day starts with rice porridge with a sole almond that is said to bring good luck to its recipient. Until the 1800s, rice was a luxury most people couldn’t afford, making the quotidian porridge one made out of oats or barley. Because rice was seen as more opulent than the local grains, rice porridge was only made for special occasions, like Christmas. But the tradition still lives on today, with rice porridge keeping its place at the Christmas breakfast table.

In a country where fish has historically played a larger role than red meat, the Christmas feast usually starts with marinated herring in various dressings, gravlax (dry-cured salmon) and roe. But where Finland has really put its own spin on Christmas is with its casseroles. The Swede casserole, potato casserole and carrot casserole are all staples of the Finnish Christmas table.

“The fact that these commonplace casseroles have become part of our celebration, that feels fairly unique to Finland,” says Nirkko. “No one even tries to gussy them up, they just sit there, on the table, in all their simplicity.”

While the vegetables are viewed as modest, the labor involved in making these casseroles takes some real effort.

“The ingredients are all simple, but the dish itself takes time to prepare, making it food for special occasions,” he says. “These days, if someone actually takes the time to make one of these casseroles, people are quite impressed with their dedication.”

The star of the Christmas meal is usually the ham, which according to a 2018 survey by Lidl is still favored by 82 percent of residents. Although ham had been consumed by the Vikings as part of their Christmas feast, it didn’t make its way to Finnish tables until the 1800s.

“The consumption of pork can be traced back to the rise of living standards in Finland, and the ability for more people to afford ham. Later merchants started advertising ham as something that was an integral part of Christmas, and created a need for it,” says Nirkko.

Christmas Sauna

Nothing is more Finnish than the sauna and it wouldn’t be Christmas without incorporating Finland’s favorite pastime. This centuries-old Christmas Eve tradition is meant to signify the break from physical labour and an opportunity for cleansing both physically and spiritually for the holidays.

Nirkko suspects that the fact that the bathing took place on Christmas Eve also contributes to Finland placing a greater emphasis on Christmas Eve than the days that follow.

“Labor used to be quite dirty, and once you were clean and the work was done, it felt pretty festive by default,” he says.

Today, saunas heat at the flick of a switch, but in the past preparing the sauna was part of the ritual. First, the sauna was properly scrubbed clean. As families would take turns bathing from Christmas Eve morning and into the afternoon, the wood-fired sauna would often be heated overnight. The sauna was only used during daylight hours, because it was believed that ancestors and elves occupied it in the dark. And the punishment for making noise in the Christmas sauna would be an excess of mosquitos the following summer.

Although not everyone has access to a wood-fired sauna, these days the tradition of joulusauna is often upheld by homeowners’ associations who heat up the building’s sauna without extra charge on Christmas Eve.

“Finns love tradition. It brings a certain sense of safety and assurance when things are done a particular way,” says Nirkko. “Having traditions also gives people the freedom to deviate from them. This makes it an opportunity to come together and figure out how to make everyone’s idea of Christmas work together, making it uniquely your own tradition.”

Related stories from around the North:

Arctic: Santa and his reindeer set off from snowy Lapland, Yle news

Canada: Is Santa’s sleigh pulled by a “he” or a “she”? The truth about Christmas reindeer, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Christmas Special: How Santa became Finnish, Yle News

United States: 64 years tracking Santa with NORAD, Eye on the Arctic

Calling Haddon Sunblom a Finn is gross cultural appropriation. Not all citizens of Finland are Finns. Åland is still predominantly Swedish, and at the time Haddon’s father was born in Åland, it was even the more so. Both Haddon and his parents all identified Swedish in their Swedish-American circles.