Canada

By Train

With almost 48,000 kilometres of track, Canada has one of the largest railways in the world.

Curiously, freight crosses the country faster by rail than passengers traveling the same route. While freight can cover the 6,000 kilometres between Halifax and Vancouver in 72 hours, it takes passengers at least 80 hours to go the same distance.

Here, the railway is for freight first. Passengers come second.

These days, passenger trains are a bit out of favour in Canada, but that wasn’t always the case. Until the rise of the airplane and the car in the early 1950s, the train was the only fast and affordable way to travel around the country.

The birth of the railway

The Canadian railway lagged a few years behind its counterparts in the United States and Europe.

For example, from 1850 onward, trains began to change the face of America. Immigrants, mainly Europeans, settled the Western prairies and then pushed on to the Pacific coast. Cities sprang up everywhere. With trains, a day’s trip overland was no longer measured in kilometres, but in tens or hundreds of kilometres. Locomotives replaced horses, while coaches gradually gave way to automobiles and train cars. Suddenly anything was possible.

It took until the 1870s for railway fever to hit Canada, but the train quickly came to play a key role in building the Canada we know today.

The building of the Canadian transcontinental railway coincided with the birth of a country.

A great story

Modern view from a passenger train crossing the Canadian Rockies.

(Timothy Stevens)A political imperative

When Canada was created in 1867, one of the conditions under which the Maritime provinces agreed to join Confederation was the central government’s promise to build an “intercolonial” railway as soon as possible.

In 1871, another big region, British Columbia, was lured into Confederation by the promise to expand the railway westwards to the Pacific coast. At the time, British Columbia was a British territory cut off from the rest of the country by nearly impassable mountains.

It was the railway that, in the earliest years of Canada as we know it today, allowed the new country to defend its sovereignty against the United States.

Some historians believe that, if not for the railway, Canada would not be the second largest country in the world. The United States would have won this title, because huge swathes of western Canada would have become American states instead of Canadian provinces.

Read

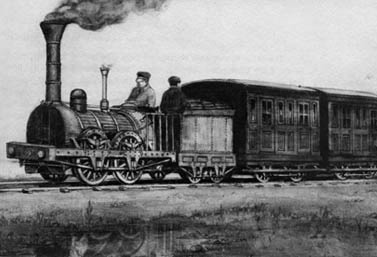

By the numbers: 1835

Period drawing of Canada’s first train, the Dorchester, in 1836

(Canadian National)This was the year in which construction began on the first stretch of railway in Canada. Completed the following year, it was at least 50 kilometres long.

The Molsons, the owners of a large brewery and one of Montreal’s richest families, financed the construction of the railway which was meant to carry freight to New York.

The Dorchester, a wood-burning locomotive manufactured in England, pulled a single car and could reach a top speed of 48 kilometres an hour. The track ran from the south of Montreal to the town of Saint-Jean sur le Richelieu, just north of the US border.

In Saint-Jean, the cargo was loaded onto steamboats that went from waterway to waterway, finally reaching the Hudson River and New York City, 500 kilometres to the south.

Did you know?

Via Rail, established in 1977, carries 80% of its passengers in the Quebec City-Windsor corridor.

(Peter McCabe/Canadian Press)Why were there so many black employees in Canadian passenger trains?

Towards 1886, a U.S. company, Pullman Palace Car, which invented the sleeping car, decided to hire only blacks as onboard attendants on the Chicago-Montreal route. This initiative, which delighted customers, soon became the company’s trademark.

Canadian railway companies decided in turn to hire many black employees to staff their sleeping cars. They carried baggage on departure and helped passengers get on and off the train.

The word “porter” subsequently came to include other types of onboard servants, such as cooks, servers and cleaners.

Onboard segregation

Working conditions were difficult for Canada’s porters. They were subject to harassment, and reported abuses of power by railway management were common.

In 1918, black employees of Canadian Northern Railway (CNR) applied to join the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway, Transport and General Workers Union. At its congress, the Brotherhood denied the application on grounds of ethnicity. Severely criticized, it reversed its decision at the 1919 congress, allowing black porters into the union but creating two classes of employees: whites and blacks. This segregation, which seriously limited black employees’ chances of promotion, was to last until 1964.

A great story

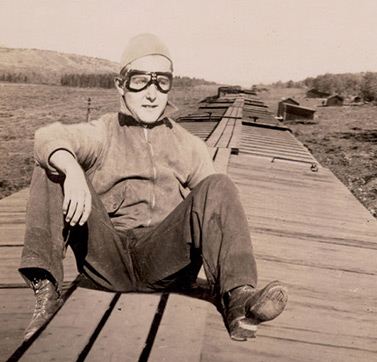

Gordon McLean

(Library and Archives Canada)The fascinating story of the hobos

During the economic crisis of the 1930s, many North Americans were out of work. In Canada, the unemployment rate hovered around 15%. The continent was in the throes of the Great Depression.

Many Canadians who were out of work refused to sit and do nothing. Instead, they decided to head off to Western Canada or the United States in search of a job.

Without money to buy a ticket, men hitched free rides on the boxcars.

Sometimes they’d ride inside the cars, sometimes outside. Some hid from view between the track and the bottom of passenger cars by laying boards across the brake rods. On these makeshift platforms, the ride was noisy, uncomfortable and, above all, dangerous.

Many hobos were seriously injured or killed. One unfortunate victim was thrown under the wheels and ripped to pieces in less than three seconds.

Gordon McLean, from the village of Tribune, Saskatchewan, was 15 years old when he became a hobo.

“I still dream of riding freight trains. I can still smell the trains, still feel the jouncing and swaying, still hear the thunderous rumbling from the wheels that penetrates an empty boxcar and the different types of rattling echoes.”

A Via Rail trans-Canada train at Toronto’s Union Station

(Via Rail Canada)The Trans-Canada Train

Tourists can ride the rails along a 6,000-kilometre cross-Canada route that takes at least six days and has three stages and two stopovers.

Leaving from Vancouver, on the West coast, you cover the longest part of the trip first. This stretch lasts a bit more than three and a half days, or 85 hours. You start by boarding a train called simply the “Canadian.”

Three weekly departures for Toronto

The trans-Canada train carries an average of 200 passengers. Three locomotives pull about 20 cars covering a total length of 600 metres. After leaving Vancouver, the train heads down into a valley before beginning its slow climb towards the snowy peaks of the Rockies. The passengers greet each other, knowing they’ll be spending several days together.

Passengers on the “Canadian” are in no rush. They have plenty of time to enjoy the trip, the scenery, new acquaintances, the magic of the train.

Traveling at 40 to 60 kilometres an hour, the train takes you 3,350 kilometres east to Toronto.

The trip is leisurely because there’s so much to see

On route, you make two tourist stops within a few hours, one in Banff and another in Winnipeg. You wind through an ever-changing landscape, from the mountains of British Columbia and Alberta through the vast wheat fields of Saskatchewan and all the way to the Northern lake region of Ontario and Manitoba. The train travels through otherwise inaccessible locations.

Sometimes you cling to the mountainsides, sometimes you pass under the mountains. If you’re lucky enough to be riding on one of the huge wood-burning trains more than 130 years old, you roll through breathtaking valleys interspersed by roaring waterfalls. Cliffs loom up on either side of the tracks. You can take some spectacular shots.

The Vancouver-Toronto one-way all-inclusive trip costs about $750 in the high season, more than twice the price of a round-trip airfare. In low season, the price is similar to the plane.

Comfortable cars and private cabins

Via Rail train making its way through forests overlooked by mountains between Jasper, Alberta and Vancouver, British Columbia.

(Via Rail/Canadian Press)The “Canadian” features a panoramic car with a 360° view, as well as a dining car (meals are included in the price of the ticket).

The sleeping cars feature cabins with stacked berths that can comfortably accommodate two people. All the amenities are there, but on a small scale, like in Japanese pod hotels: two portable chairs, a toilet, towels, a mirror over a sink with electrical outlet, baggage space, a big window with blind, small cupboards, sheets, pillows and blankets. Passengers also have access to a shower near their room.

During the trip, you reset your watch every day to the new time zone, easing into the three-hour time difference between Vancouver and Toronto.

In addition to movies at night and solitary moments to enjoy the scenery by day, you have time to chat with travellers from all over the world.

In Toronto

Once you reach the Queen’s city, you can continue on to the Port of Halifax on the Atlantic coast. If that’s your destination, you have another 1,300 kilometres to go.

First, you board the “Corridor,” which runs at an average speed of just over 100 kilometres an hour. It reaches Montreal barely five hours later. You spend the night there and, next morning, board another train, the “Ocean,” which pulls into Halifax 22 hours later.

Discover

Railway History. The Canadian Encyclopedia

Watch

Building the country with Canadian Pacific trains (in French)

Crossing Canada by train

History of one of the world’s longest railways

A steam locomotive crossing a massive wooden bridge in turn-of-the-century British Columbia

(Library and Archives Canada)Forty years after its construction, the transcontinental railway remains one of the greatest technical wonders of the modern world.

It was born gradually, in keeping with a promise made by the first Prime Minister of Canada, Sir John A. Macdonald, at the time of Confederation. Back then, British Columbia was a crown colony. Located on the west coast of North America, it was cut off from the rest of the continent by the Rockies. There were no roads and the rivers were treacherous. The only way through was a difficult trek on foot, in summer, with the help of mules.

British Columbia was lured into joining the new Canadian Confederation by a promise to build a national railway through the mountains. In 1871, Sir John A. Macdonald’s government promised that a railway would be built within ten years.

The promise was not fulfilled until 1885, because the work was difficult in certain rugged regions.

An all-Canadian railway

A railway serving Western Canada could theoretically have run through the US prairies. The engineers would have saved themselves a lot of trouble and the politicians would have saved a lot of money. In 1870, Canada set out to find a solution. From the outset, it decided that it didn’t want to pass over American soil. What it wanted was an all-Canadian railway. It was a question of national strategy.

However, this kind of route was impractical. It had to cross 1,600 kilometres of rugged country in Eastern Canada, marshland in Central Canada and daunting mountains in the West! Sir John A. Macdonald and other high-level politicians, influenced by bribes, decided to award the major federal construction contracts to their business cronies.

In 1874, as a result of this scandal, Sir John A. Macdonald’s Conservatives were voted out of office, leaving the transcontinental rail project in the lurch. Construction progressed slowly in some parts of the country due to a lack of government funding, while elsewhere it ground to a halt.

In 1878, Sir John A. Macdonald was re-elected and construction resumed in earnest. This time they tackled the stretch of the railway slated to go through the mountains.

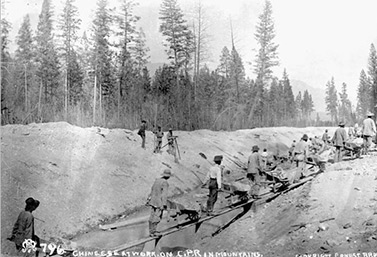

Hundreds of workers

In 1884, Chinese workers building the trans-Canada railway through the mountains.

(Canadian Pacific)The task was enormous and workers started being brought in from China. Nicknamed “coolies,” the Chinese labourers made only $0.75 to $1.25 a day, not including expenses, half the wages of white workers.

In reality, these people were not much better than slaves. They bought their food from their employer, who also sold them medical care at exorbitant prices.

Often the Chinese workers could not put aside any money at all, even after three months of labour. Some realized that they would never be able to return to their homeland. The Chinese were often assigned to the most dangerous jobs, even handling unstable explosives. The families of the Chinese who were killed received no compensation or even notification of death.

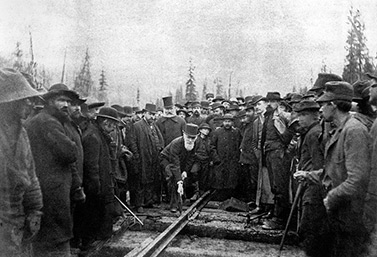

On November 7, 1885, in the Rockies, driving of the “last spike” on the transcontinental railway.

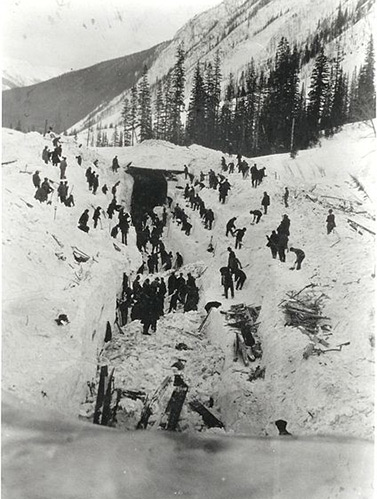

(Library and Archives Canada)Danger in the mountains

The most hazardous stretch of the construction was along Rogers Pass, a region known for its jutting cliffs, deep, narrow valleys, glaciers, countless avalanche routes and heavy snowfall or rainfall. But it was the only place, for many kilometres around, where the otherwise impenetrable Rockies could be crossed. This was the missing link in a coast-to-coast Canadian railway. A better screenplay could hardly be imagined…

One very hard year and many incidents later, the 10-kilometre stretch was finally completed. However, it failed to meet the construction standards and would be the scene of many fatal accidents.

Death Pass

The engineers were forced to build a seven-kilometre segment on a steep incline with a slope of about 5%. This was four times the maximum slope recommended for railways at the time. Even on modern railways, the slope rarely exceeds 2 %.

An automatic braking system was installed along the length of the incline. The speed limit was set at 10 kilometres/hour for descending trains and special locomotives fitted with powerful brakes made the trip.

Despite these precautions, there were many fatalities in the first 25 years of operation. In winter, there was the added threat of deadly avalanches.

This finally convinced the government to build an 8-kilometre tunnel, at great cost, directly through the mountain under Rogers Pass.

A tourist train

Towards the turn of the century, the transcontinental railway changed the way North Americans saw the mountains. For many people, the Rockies were no longer an obstacle to growth, but a tourist attraction. The first mountain hotel, Glacier House, was built. Standing near the tracks, it was wildly popular. Hotels that are now world-famous, like the Banff Springs Hotel and Chateau Lake Louise, were to follow.

By the numbers: 1886

First Canadian Pacific train trip on the transcontinental railway, June 30, 1886

(Library and Archives Canada)That year, for the first time, it was possible to cross Canada by train.

The first transcontinental passenger train, the Pacific Express, left Montreal on June 26, 1886 and pulled into Port Moody, near Vancouver, on July 4 , ending British Columbia’s isolation and saving the former British colony from being assimilated by the United States.

In the transcontinental railway’s first year of operation, service was interrupted for months on end because there was an average of 12 metres of snowfall each winter on the stretch of track through the Rocky Mountains. In the end, a costly system of snow sheds was built.

One disaster after another

Despite these precautions, a terrible avalanche occurred on March 4, 1910 in Rogers Pass, killing 58 railway workers who were clearing the track after a previous avalanche. Three days earlier, a similar disaster had occurred in Washington State, hurling two trains to the bottom of a canyon and killing 96 people.

Today, Rogers Pass has been designated a national heritage site to commemorate its role in the birth of the Canadian nation. Like the transcontinental railway, Rogers Pass is an important symbol of Canadian nationalism.

Did you know?

The Rocky Mountaineer

(Rocky Mountaineer)The Rocky Mountaineer, smallest train in the Rockies

If you have your heart set on viewing the wild and breathtaking scenery of Canada’s western mountains, you don’t need to pay for a ticket on the trans-Canada railway.

The Rocky Mountaineer, a celebrated tourist train, offers you mountain views in absolute comfort on a two-day excursion starting from Vancouver.

After crossing the Fraser Valley, the Rocky Mountaineer takes passengers to the city of Kamloops, where it makes an overnight stop. The second day, travellers can head north through the mountains to Jasper or south to Calgary.

Watch

Best Vacations in the World: Rocky Mountaineer

All Aboard the Train! Rocky Mountaineer is leaving Vancouver

A great story

The Petit Train du Nord in the upper country

- Father Antoine Labelle, father of colonization and King of the North, towards 1872, aged 39

(Société d’histoire de la rivière du Nord)

The Petit Train du Nord is one of the most famous passenger and freight train lines in the history of Canada. Starting in 1873 and for more than 100 years, it opened up the woodlands and mountains north of Montreal to immigrants from Europe and French-speaking Quebecers. Leaving from Montreal, the train headed due north, ending its run 200 kilometres later in the bucolic rolling countryside of the Mont-Laurier region.

The Petit Train du Nord was the brainchild of Antoine Labelle, an ambitious Catholic priest. In 1870, Father Labelle was abbot of Saint-Jérôme, a small village about 50 kilometres north of Montreal. For nationalist reasons, he wanted to stop the exodus of French-Canadian workers to New England, the United States or Western Canada. He dreamed of a French Catholic reconquest of the northern Canadian territories between Montreal and Winnipeg.

An impressive orator and indefatigable lobbyist, the imposing priest (6 feet and about 300 lbs) completed the first stage of his project north-east of Montreal. He persuaded the federal government to invest in building a railway that would serve what was then known as the Pays d’en Haut (upper country).

King of the North

On October 9, 1876, when the Montreal-Saint-Jérôme segment of the Petit Train du Nord was officially inaugurated, one of the two locomotives running on the line was baptized “Rév. A. Labelle.” Before long, the train had new French-speaking villages and tourist facilities springing up along the route. Father Antoine Labelle earned the nickname the “King of the North.”

The year 1981 marked the end of the Petit Train du Nord’s monopoly as a means of transportation between Montreal and the Laurentides. Today, a 200-kilometre bike path runs along the site of the celebrated train’s former tracks.

Discover

Le Petit Train du Nord. (in French)

Dream journey in a legendary train. (in French)

See

Les belles histoires des pays d’en haut (in French)

- Father Antoine Labelle, father of colonization and King of the North, towards 1872, aged 39

Chugging Through the Daily Landscape of Canadians

Via Rail Canada

(Canadian Press/Peter McCabe)The railways gave birth to modern-day Canada. Trains, on the other hand, now play a very minor role in daily lives of Canadians.

Freight certainly still travels by train in Canada, but people no longer do. Some people have never taken the train in their life and have no intention of doing so.

Canadian airports process some 159 million passengers each year; trains carry only 4 million.

Canada’s national passenger carrier is called Via Rail. This railway company operates only about 500 weekly runs and has no more than 73 locomotives and 426 cars (2016). This modest performance partially reflects the fact that, for the past 70 years, the federal government has been investing massively in road and air networks.

Idling trains

In Canada, the trains make slow progress. In every sense. Their speeds are also inconsistent. Via Rail owns only 223 of the 12,500 kilometres (3%) of the track used by its trains, which means that freight trains have priority on Canadian railways.

Freight carriers are in a position to dictate not only the number of periods in which passenger trains have the right to use their tracks, but also the time of day or night.

Canadian railway freight transportation giants

In Canada today, no less than 70% of freight travels by rail. In 2002, the percentage was 60%. The industry has been growing steadily since the 1980s.

Canadian National (CN) is one of Canada’s two largest railway freight transportation companies. The other one is CP, or Canadian Pacific which, as its name indicates, mainly covers western Canada.

CN is Canada’s only transcontinental railway company and one of the seven biggest companies in North America.

CN has been part of the daily landscape of Canadians for 155 years. In recent years, the company has gained a high profile in the United States, having significantly expanded its network by absorbing several US companies. Today it operates a 28,200-kilometre transcontinental network serving eight Canadian provinces and fifteen American states.

CN is the only North American railroad to cross the continent from east to west and north to south, and to serve ports on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts and the Gulf of Mexico.

By the numbers: 1976

CN Tower was opened to the public on June 26, 1976. Each year, 2 million tourists ride the glassed-in elevators 342m up to the SkyPod with its wide observation decks and the world’s highest revolving restaurant.

(Kevin Frayer/Canadian Press)This is the year in which our biggest railway company, Canadian National, completed the construction of Canada’s celebrated national tower, the CN Tower, in the heart of Toronto.

At a height of 553 metres and 147 stories, it was the world’s tallest freestanding structure until the recent construction of the Dubai Tower.

The SkyPod, 447 metres above ground level, is a small observation platform almost 100 metres above the main look-out level.

Until 2008, when the Shanghai World Financial Center was inaugurated, the SkyPod was the highest public observation post in the world.

The CN Tower is one of the seven wonders of the modern world, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers. It is still the world’s highest telecommunications tower.

A great story

Drawing of a high-velocity Bombardier train in China

(Bombardier Transportation Inc.)Canada, an engine of global railway growth

In the railway industry, Canada is like a master shoemaker wearing worn-out shoes. Although it has no high-speed, modern trains like the Japanese Shinkansens or European TVGs, our country is the homeland of Bombardier, the impressive multinational that manufactures, among other things, the world’s best railway equipment. Many of the world’s great trains and subways use cutting-edge or high-speed equipment developed by Bombardier.

Bombardier Transportation, Bombardier’s rail division, not only produces rolling stock (trains, coaches, streetcars), but also rail safety equipment.

London Underground riders feel safe thanks to Canadian rail expertise. Bombardier also designed all or part of the rolling stock for the New York, London, Montreal and Toronto subways.

Did you know?

A TGV on a European line

(AFP/SÉBASTIEN BOZON)What is Canada waiting for?

Most Canadians are convinced that, sooner or later, their country will have no choice but to join the global trend and put its first high-speed train (TGV) on the rails.

Canada is the only G8 country without a high-speed rail. China, France, Germany, Russia and Turkey are just some of the nations that are banking heavily on the potential socio-economic benefits of TGVs. Even the United States, where train culture lags a bit behind the rest of the world, has a $50 billion plan to create an extensive interstate network.

But for almost 40 years, Canada has refused to move forward on the issue.

A number of scenarios have nonetheless been developed for the Quebec City-Windsor, Montreal-Toronto and Montreal-New York corridors. And in recent years, there have been new proposals for the imminent arrival of TGVs in the Montreal-Boston, Calgary-Edmonton and Vancouver-Seattle corridors.

The TGV stokes the imagination of Canadians

Just imagine: at 260 kilometres an hour, the trip from Montreal to Toronto would only take two and a half hours! As things stand, it takes twice that long to make the trip by train or car. By plane, counting wait times, it usually takes three hours to get from one city to the other.

Proponents claim that a TGV in the 1,000-kilometre Quebec City-Windsor corridor would significantly increase Canada’s competitiveness, improve Canadians’ quality of life, ease traffic congestion and drive growth in tourism. Other spinoffs would include green job creation, better air quality and more efficient freight transportation.

With such large distances to cover, the TGV would be the biggest Canadian infrastructure project since the construction of the Saint Lawrence Seaway.

Studies show that it would cost $20 to $30 billion to build a high-speed rail line in the Quebec City-Windsor corridor.

Only the federal government has deep enough pockets to pay for an initiative like this but it is reluctant to spend this kind of money, afraid that it will be left with a “white elephant” on its hands.

Too sparsely populated

Six cities on the potential TGV route in eastern Canada

The TGV’s detractors say that Canada’s population density is not comparable to that of China or the United States. They say the TGV would be financially viable and likely profitable, but certainly not cost-effective.

Public opinion, however, is very much on the side of the TGV. The latest surveys on the matter show that about 80% of Canadians are in favour of building a high-speed rail.

The two camps have arguing off and on for almost 50 years.Read

Watch

CN Turbo Train – Rare Early Film

The Go Train, a modern-day success story

An afternoon GO Train runs through a Toronto suburb in April

(Joe Fiorino/CBC)Despite the problems with passenger trains in Canada, commuter trains, starting with Toronto’s famous GO trains, have been a huge success. Montreal’s commuter trains have also seen a sharp increase in ridership. There are now more than 47 million annual trips on Toronto’s commuter trains (2018) and more than 21 million (2017) in Montreal.

Traffic problems in both cities were responsible for the increase in ridership, which took many officials by surprise. It was so sudden and intense that in 2007, half the users of the 31 Montreal-bound commuter trains during morning rush hour could not find a seat and had to stand.

In just about ten years, Toronto and Montreal have climbed to 5th and 6th place for the most train commuters among North American cities. Only New York, Chicago, Philadelphia and Boston do better.

Discover

Riding the subways and the Canadian Sky Train

An afternoon GO Train runs through a Toronto suburb in April

(Joe Fiorino/CBC)Only two metropolitan areas in Canada have an underground railway: Toronto, with a population of 5.5 million, and Montreal, with 3.5 million.

The Toronto rail subway

The Toronto subway is the oldest. The Toronto Transit Commission opened its first line in 1954. The system has 4 lines and 75 stations along 77 kilometres. Almost a million people ride the subway each day.

The Montreal rubber-wheeled metro

The Montréal metro was created in 1966. It is the largest and busiest in Canada. Traffic on the Montréal metro has more than doubled since its opening: the number of passengers transported has risen from 136 million in 1967 to 367 million half a century later.

The Vancouver SkyTrain

Since 1986, this western city, the third largest in Canada, has had the world’s longest and most futuristic elevated railway, the SkyTrain. It’s the same as a subway, but runs above ground instead of underground.

The elevated railway is ideal for Vancouver, where the ground frequently shifts. The city is built along the Pacific coastline, on a thin strip of land where seismic activity is significant.

The SkyTrain system has 69 kilometres of elevated railway, making it the longest automatic railway in the world. It has 53 stations on 3 lines, and about 400,000 riders per day.

The SkyTrain also crosses the longest bridge reserved exclusively for an elevated railway, the Skybridge, which spans the great Fraser River.

Bombardier, SkyTrain’s inventor

The SkyTrain uses Bombardier’s Advanced Rapid Transit (ART) technology. With ART, train operations are fully automatic. There have been no derailments or collisions on this futuristic railway since it was inaugurated more than 35 years ago. Humans have only two roles on the SkyTrain: taking tickets and driving the trains in for repairs in case of technical problems.

Invented by Canadians

The Bombardier JetTrain in a 2006 photo

(Bombardier)The JetTrain

Bombardier Transportation has developed a high-speed, experimental train for the North American market, the JetTrain, the first to run on non-electric high-speed rail technology. Powered by a Pratt & Whitney turbine engine, the JetTrain can reach speeds of 240 kilometres an hour.

A JetTrain locomotive weighs 20% less than a traditional locomotive. The JetTrain produces 30% less pollution and is several decibels quieter than gas turbine trains.

The JetTrain is an alternative to the traditional European TVG. It is designed to equal the speed and acceleration of electric trains, without the cost of building electrified tracks. Jet-propelled like an airplane, it saves on the cost of installing electrified lines over long distances. Although slower than a TGV, the JetTrain could use existing North American rail lines.

In the JetTrain, the traditional diesel locomotive is replaced by a locomotive using a 4,000-kilowatt gas turbine. With the right signalling equipment and track, a classic six-car passenger train could reach a top speed of 240 kilometres an hour.

In the early 2000s, Bombardier enthusiastically promoted the JetTrain to potential purchasers, including Amtrak in the United States and Via Rail in Canada. The Florida Overland Express project made the most headway. This train was supposed to carry passengers between Orlando and Tampa in Florida, USA. It was scheduled for completion in 2009, but the population demanded a referendum on the issue. Most people voted to discontinue the project due to its prohibitive cost.

In Canada, Bombardier unsuccessfully presented its product to Via Rail as a replacement for trains running in the country’s busiest corridor, Quebec City-Windsor.

Photo Album