Canada

On Foot

They walked on snow!

If you live in Canada, you can expect an average of just over 200 centimetres of snow every year. Some Atlantic regions sometimes get close to twice that amount.

No matter where they live, Canadians are experts at getting around on snow and ice.

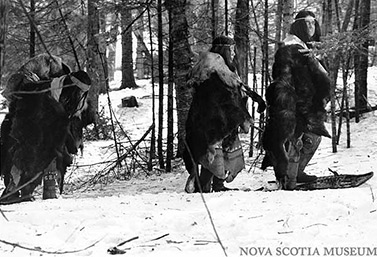

When the Europeans first began colonizing North America 500 years ago, they learned how to use snowshoes by imitating local Aboriginal peoples who had been mastering the art of snowshoeing for thousands of years, and could even use them to run in the snow.

Until the emergence of skis in the late 19th century, snowshoes were essential to the survival of the coureurs de bois—white hunters who tracked game and traded with Aboriginal peoples.

The secret to snowshoeing

Snowshoes, attached to the walker’s boots, increase the contact surface with the snow, providing the necessary support to propel the body forward. They prevent walkers from suddenly sinking into the snow, which could cause muscle or bone injuries.

You can walk quite quickly with snowshoes, provided the snow isn’t too soft. Expert snowshoers look like they’re running on the snow. As with cross-country skiing, rhythm is key.

(Troy Wayrynen/The Associated Press)

The dual origin of snowshoes

This mode of travel is unique to the snowy regions of North America and part of Western Siberia. Snowshoes were invented in Central Asia between 4,000 and 6,000 years ago, and were brought to North America by the Inuit who crossed the Bering Strait. However, snowshoes did not only originate in Asia, as was believed for a long time.

Aboriginal peoples in Canada’s North are believed to have developed the art of snowshoeing independently of todays Inuit who came from Siberia.

There are significant differences in the design of Inuit snow shoes, which are fairly simple, and Native American snowshoes, which are narrower and therefore better suited to walking on snow.

An Aboriginal tradition

Almost all of Canada’s Aboriginal peoples have been using snowshoes for a very long time. Although they come in a variety of shapes, snowshoes are one of the few cultural elements common to Aboriginal tribes who sometimes live 5,000 kilometres apart. The Athapaskan peoples of Western Canada and the Algonquin in the northeast part of the country have truly mastered the art of snowshoe-making.

Traditionally, the frame was made out of ash wood, which is durable and flexible. The thick lacing was made of moose, deer or caribou skin. Modern snowshoes are designed according to the same principles, but are made of different materials: light metal, nylon and reinforced plastic. Almost all modern snowshoes are turned up at the front to prevent an accumulation of snow.

Snowshoes are essential gear for forest rangers and farmers.

Although most people use snowmobiles or skis to get around Canada’s forests in the winter, snowshoeing has become a very popular recreational activity as well, and sporting good stores have a wide variety of models on offer.

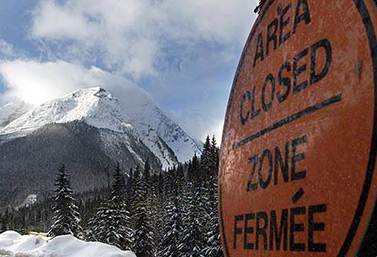

A sign in Glacier National Park, British Columbia, warns hikers that the trail is closed because of an avalanche that killed seven teenagers a few hours earlier.

(Adrian Wyld/Canadian Press)The world’s longest natural trail

Canadians’ preferred form of physical activity is walking, but to enjoy the outdoors in winter, they need snowshoes, skis or skates. They get out in the forests, even in the middle of winter, sharing the trails with snowmobilers or people travelling by horse or dog sled.

Across North America, there are almost 400,000 kilometres of trails that are regularly groomed, even in the middle of winter.

A number of trails follow former train tracks and are ideal for snowmobile rides in the winter and bike rides in the summer.

Almost 5,500 kilometres from east to west

The Trans Canada Trail (now called the Great Trail) is the longest recreational trail network in the world. The Trail stretches 24,000 km, joining Canada’s Atlantic, Pacific and Arctic oceans.

An agency, the National Trail Association of Canada, coordinated its construction for 25 years and supervised the actions of thousands of volunteers across the country. It led one of the largest volunteer-based projects ever undertaken in Canada.

Each metre of the trail cost about $35.

A very popular trail

The Trans Canada Trail is used by people seeking to explore Canada’s many diverse landscapes. It connects the country’s three oceans: the Atlantic, the Pacific and the Arctic.

Four out of five Canadians live within 30 minutes of the Trans Canada Trail.

Most of the trail runs across southern Canada, but there is also a northern branch that connects Edmonton to Tuktoyaktuk via Inuvik, in the Northwest Territories. The trail directly links 1,000 of Canada’s 5,000 towns and cities.

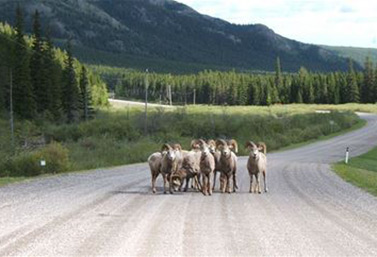

Wild sheep and mountain goats often force drivers to stop in the Crowsnest region, in Western Canada.

(CBC News)Read

Watch

Trans Canada Trail – Your Trail. Your Journey.

Trans Canada Trail in fast mode.

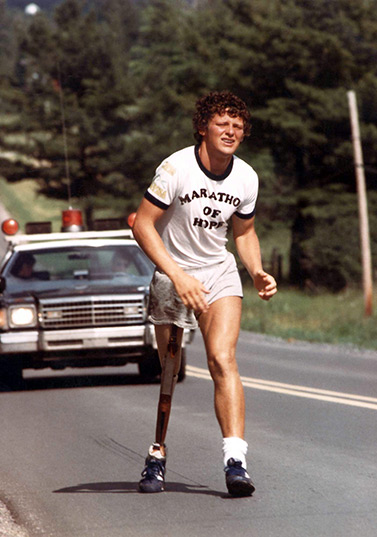

Terry Fox running his Marathon of Hope

A great story

Crossing Canada on one leg

If you kept up a moderate pace of 10 kilometres an hour for 10 hours a day, it would take you 55 days to cross Canada. Very few Canadians have achieved this feat. Those who try are generally supporting a humanitarian cause or raising funds for medical research.

40 years ago, a young man who lost one of his legs to cancer tried to take on the challenge, running on an artificial leg. He became known the world over and is today one of Canada’s greatest modern-day heroes.

The courageous Terry Fox

In 1980, Terry Fox was 22 years old. His right leg had been amputated three years earlier, following a cancer diagnosis. He decided to run across Canada to raise funds for research and help other cancer victims. He called his run the Marathon of Hope. In the spring of 1980, he marked the start of his marathon by dipping his artificial leg in the frigid waters of the Atlantic Ocean near St. John’s, Newfoundland.

The national media flocked to follow him every step of the way, broadcasting images of Canadians gathered along streets and highways, waiting for Terry Fox to run by. People applauded and encouraged him, and gave him money.

Galvanized by the crowds, Terry Fox ran on his artificial leg from morning to night, day after day. He tirelessly carried on, despite the pain and abrasion caused by his prosthesis. By the time he reached Northern Ontario, he had covered close to half the course.

His cancer caught up to him

When he began coughing and feeling persistent chest pain, Terry Fox realized the cancer had spread to his lungs. After 143 days of non-stop running, he gave up. At an emotional press conference, he told Canadians not to worry—he would continue as soon as he was back on his feet. He spent 10 months in hospital and battled the disease as best he could. Sadly, at the end of June 1981, the media announced to Canadians that their modern-day hero only had a few more hours to live. Terry Fox died on June 28.

His illness got the better of him, but he left behind a legacy of hope that, even today, inspires millions around the world to continue his fight.

This is the story behind the famous Terry Fox Run that has thus far raised about $725 million worldwide for cancer research.

Montreal’s Underground City. In the foreground is the copper fountain in Place Montréal Trust—the tallest fountain of its kind North America.

Did you know?

It’s easy to walk underground in Canada

Canada’s two largest cities, Toronto and Montreal, have the largest underground cities in the world. Not all of Montreal is visible from the sky, since just over a third of its downtown area is in fact underground. Concealed beneath Montreal’s streets is the largest underground city in the world, consisting of a network of 32 kilometres of corridors and stores.

Working and having fun in Montreal without ever seeing winter

Montreal’s underground tunnels connect a wide array of restaurants and boutiques for every budget with dozens of office towers and residential complexes.

It was officially named RÉSO in 2004. The RÉSO is used by nearly 183 million people every year.

The Underground City is also linked to four universities, luxury residences, hotels, seven metro stations, and two suburban train stations. Over 500,000 people out of a population of close to 4 million walk in underground Montreal every day.

Montreal’s underground network dates back to 1967, the year the city’s first metro stations were opened.

Toronto has the world’s second largest underground network . . . for now

Canada’s biggest city might soon steal the limelight from Montreal. PATH is what Torontonians call their 30-kilometre underground walkway (only 2 kilometres shy of Montreal’s network).

Connecting office buildings, parking lots, shopping centres and subway stations, PATH is already the world’s largest underground shopping complex, according to Guinness World Records with 371,600 square metres (4,000,000,000 square feet) of retail space.

Toronto and Montreal have 3.7 and 3.6 square kilometres of underground retail space, respectively.

Toronto’s underground network dates back to 1900. At the time, Eaton’s, Canada’s largest department store, decided to build a tunnel to allow its customers to walk from the main store to another commercial building without going out onto the street.

Some Canadian cities, particularly in the West, have opted for other ways to protect residents from winter. Calgary and Edmonton, in the province of Alberta, have connected buildings through a network of glass-enclosed walkways built above street level. In these downtown areas, as in Montreal and Toronto, you never have to step outside during the winter months.

See

Watch

Montreal’s Underground City (in French)

A snowmobile trail in Quebec, during International Snowmobile Safety Week. Peace officers are giving snowmobilers safety reminders.

(Radio-Canada)Racing across the snow

The fastest way to get around on snow or frozen lakes is by snowmobile—a small, motorized vehicle with tracks at the rear and skis in the front.

Riding across the snow at 70 kilometres an hour is an exhilarating experience. Wearing well-insulated clothing and a protective helmet with a visor, snowmobilers ride into the wind, leaving behind a trail in the snow. Seventy years ago, this would have been impossible.

Snowmobile group expeditions

Snowmobile rides and expeditions are a familiar sight today in Canada. In 1990, thirty years after their invention, there were 430,000 snowmobiles in the country. Today, there are over a million! Ninety per cent of the world’s snowmobiles are driven in North America.

Canada and the United States have 400,000 kilometres of trails specifically designed for snowmobiles. You can cross Canada on a snowmobile in just two weeks!

Snowmobiles are as fast as cars

On most marked trails, the maximum speed for snowmobiles is 70 kilometres an hour, although the more powerful vehicles can easily reach speeds of up to 120 kilometres an hour. It is possible to make mechanical changes to snowmobiles, allowing them to reach maximum speeds of 170 to 190 kilometres an hour.

The dark side of snowmobiling

In Canada, close to 9 out of 10 snowmobiling accidents occur at speeds of over 50 kilometres an hour. The risk of accidents is very high, despite awareness-raising efforts on the part of police. According to different studies, less than 20% of accidents occur on specially marked snowmobile trails.

The risk is therefore much higher off trail. In Canada, roughly 75% of snowmobile accidents result from an impact with a mound of snow, a rock or some other type of bump. Almost one time in five, the accident involves a collision between two snowmobiles, and approximately 90% of accidents occur at night.

Nine times out of ten, the driver involved in the accident has a blood alcohol level above the legal limit.

Did you know?

Snowmobiles have seen many improvements since they were invented in the 1950s and now have a much sleeker look.

About snowmobiles

- In Canada, the average cost of a snowmobile is just over $9,000.

- A snowmobile travels on average 1,600 kilometres per season—slightly more than the distance between London and Rome.

- Snowmobile owners spend approximately $4,000 a year on outings.

- All snowmobiles must be registered and their owners must take out third-party liability insurance (minimum $500,000).

- The minimum age to drive a snowmobile is 16 years.

- The police regularly carry out surveillance operations on marked trails and hand out speeding tickets.

Invented by Canadians

Bombardier’s B7 snowmobile in the late 1930s

Photo: J. Armand Bombardier MuseumThe Ski-Dog or Ski-Doo

In the late 1910s, the U.S. company Ford designed the first motorized vehicle able to travel on snow. It was called the Snow Car and was a modified version of the Ford Model T. The undercarriage was replaced by skis in the front and metal tracks in the rear. The Snow Car looked more like a tank than a snowmobile. Slow and heavy, it could not travel in snow that was too deep, but had a cabin to protect the driver from the cold.

The birth of the snowmobile

It was in Quebec, in 1936, that the first true prototype of the snowmobile was invented by Joseph-Armand Bombardier, founder of the famous Canadian multinational Bombardier.

Snowmobiles in the 1930s used a rear track system partially made of rubber. However, their overall performance was disappointing.

Years later, after losing one of his sons whom he had not been able to transport to hospital during the winter, Joseph-Armand Bombardier went back to the drawing board.

He equipped his snowmobile with a lighter engine and a continuous track system that was revolutionary at the time. By the late 1950s, the vehicle was ready for market.

It was originally supposed to be called the Ski-Dog, but the “g” in the typed text that Joseph-Armand Bombardier sent to the advertising company looked more like an “o.” To avoid delays and additional marketing costs, he decided to call his snowmobile a Ski- Doo instead.

A huge success!

By the mid-1960s, snowmobiles were replacing dog sleds in Canada’s isolated Arctic regions, becoming the Inuit’s main mode of transportation.

However, most Canadians considered snowmobiles a luxury product. Sales rose significantly in the 1970s only to drop dramatically in the 1980s, when North America was hit by a severe recession. Twenty years later, the snowmobile market was back on track with an annual sales growth of between eight and nine percent.

Read

Inuit members of the Canadian Rangers—a force put in place in 1947 to monitor the Far North and alert the military

(Department of National Defence)Protecting the Far North against foreign attack

The Arctic covers close to 40% of Canada’s land mass (four million square kilometres). Approximately 80% of Canadians live in the southern part of the country, less than 160 kilometres from the U.S. border. They are unaware of what is happening in Canada’s Far North—the land of the Inuit and midnight sun.

For close to 70 years, Canada’s Far North has been preparing for a possible foreign military attack.

Five thousand Inuit to protect Canada’s North

For several decades, 5,000 Aboriginal civilians have been travelling up and down the region near the pack ice. They are Canada’s first line of defence in the Far North.

The dog teams of the 1940s have been replaced by powerful snowmobiles, but the nature of the job is essentially the same. Equipped with binoculars and rifles, these patrol officers keep a close eye on the shoreline and Arctic Ocean.

They’re ready to alert the Canadian army, stationed several hundred kilometres south, to any attack or surprise invasion.

Officially, the Canadian government is most fearful of a Russian attack. In reality, the government is wary of all the countries (even the United States) that are challenging some of Canada’s territorial rights in the region.

Watch out for the Japanese!

During the Second World War, the Canadian government became seriously concerned about the lack of an active military presence in the Far North. Countries that neglect part of their territory run the risk of losing it. In the 1940s, the Canadian Rangers officially became the “guardians” of Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic, and the eyes and ears of the military.

Canada was not content to have only the Rangers assert its sovereignty in the Far North. In the 1950s, the government made the controversial decision to uproot entire Inuit villages and relocate them further north, often in makeshift camps.

The threat of a Japanese invasion in Alaska led Canada and the United States to work together on building roads and military infrastructure.

Watch out for the Soviets!

At the height of the Cold War, Canada and the United States formed a more official partnership, establishing the North American Aerospace Defense Command, more commonly known as NORAD. Both countries were concerned about their powerful Soviet neighbour and its long-range bombers.

So they built radar lines all along the 69th parallel, including a distant early warning system called the DEW Line. This system, consisting of 63 stations (42 in Canada), monitors the skies over the Arctic to this day.

Watch out for the Chinese and the Americans!

Canada claims that the Northwest Passage, in the Arctic Ocean, lies within its internal waters. With global warming, it will become increasingly difficult for Canada to assert this sovereignty.

The Americans are challenging Canada’s claims. They dream of having an international marine passage that would reduce the travel times of freight ships to Europe and China by 30 percent.

The 5,000 Canadian Rangers who are monitoring the region are playing a more important role than ever. They are better equipped, with the most powerful snowmobiles in the world, and are backed up by NORAD and its long-range radar warning system.

Using a satellite as well

Canada recently completed its Polar Epsilon project, which provides real-time images via the RADARSAT-2 earth observation satellite. In about 10 minutes, the Canadian Forces are alerted to any suspicious activity. Military personnel are travelling more often to the Far North to carry out annual exercises in which the famous Rangers participate as well.

Nanook, Nunalivut and Nunakput are three major military operations that take place every year in Canada’s Far North.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper during a visit in the northern territory of Nunavut, in August 2009. With him are some ministers and several Inuit Rangers.

(Joanna Awa/CBC)

Canadian soldiers on patrol during a military operation in Nunavut, in 2007.

(Dianne Whelan/Canadian Press)Watch

National Defence Minister and Operation Nanook

A great story

Emily Nishikawa is a talented Canadian athlete who lives in Whitehorse, in the Northwest Territories. Here she is competing in Canmore, Alberta, in January 2013.

(Jeff McIntosh/Canadian Press)Downhill skiing: a Scandinavian invention popularized by Canadians

Every year, close to 4.5 million Canadians go downhill skiing, cross-country skiing or snowboarding. The technique of using skis to glide across the snow dates back to the time of the Vikings.

Around the year 1000, the Vikings lived for several decades on Canada’s East coast where they established colonies. They showed the Aboriginal peoples in the region how to travel on long planks of wood.

But skiing didn’t really take off until the mid-19th century when Scandinavian miners arrived in Canada. These direct descendants of the Vikings came to prospect in the northern part of the country during the Gold Rush. They got around on “snow skates” three or four metres long and organized informal downhill skiing competitions, much to the delight of the local population.

In 1879, newspapers in Eastern Canada gave detailed accounts of a Norwegian-born Montrealer, Mr. Birch, who was the first man to ski 230 kilometres from Montreal to Quebec City.

In the early 20th century, the first major ski clubs were founded in Montreal (1904), Toronto (1908) and Ottawa (1910).

During the Second World War, skiing was part of many soldiers’ training. The quality of the equipment had improved and it was much more affordable. After the war, skiing started to become popular among young families who could enjoy the sport without spending a fortune. This popularity spread to the entire middle class in 1955, when several technical improvements were made to skiing equipment, such as stretch pants, boots with buckles and metal skis.

Starting in the 1960s, ski resorts became popular weekend destinations.

Did you know?

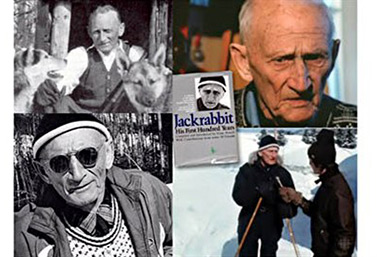

Herman Smith-Johannsen, aka “Jackrabbit”

(Radio-Canada)Two million Canadians go cross-country skiing at least once a week.

This activity started gaining in popularity towards the end of the 1920s. At the time, the Canadian Pacific Railway Company was offering its first winter excursions to small villages in Eastern Canada. Groups of skiers cut trails in the forest that would later form a network

Cross-country skiing owes much of its current popularity to the efforts of one man: Herman “Jackrabbit” Smith-Johannsen (1875–1987).

Nicknamed “the jackrabbit,” this athlete tirelessly promoted skiing in the Lake Placid region in the United States, as well as in the provinces of Quebec and Ontario.

From the 1920s to the 1960s, Herman Smith-Johannsen helped to build ski-jumping ramps and to cut cross-country trails on both sides of the Canadian border. He was finally recognized in the 1970s and 1980s, when the popularity of skiing reached new heights.

Playing cowboys and Indians

A cattle-breeding ranch in southern Alberta

(CBC News)Cowboys were originally farmhands who tended cattle herds.

The Wild West is, of course, strongly associated with U.S. history, but Canada also has its folklore from the western plains. Back in the day, these vast regions were populated by colourful cowboys who rode horses, wore leather hats and carried revolvers.

Today, most cowboys have traded their guns for cellphones and no longer act like outlaws. In the Canadian Prairies, which has a surface area twice the size of France, they can be easily spotted from the highway. Sitting tall on their horses, they tend horses and cattle in vast grazing lands known as ranches.

Vacationing in cowboy country

Rather than observe cowboys on their ranches from a distance, you can meet them by travelling along a unique trail in North America: the Cowboy Trail.

Visitors on the trail can travel from ranch to ranch and, for a few hours or several days, can truly get a sense of what cowboys are all about.

The Cowboy Trail covers 721 kilometres and extends from east to west across the southern portion of Saskatchewan and Alberta. It is particularly picturesque in southern Alberta, where it winds for dozens of kilometres along the foothills of the Canadian Rockies.

It takes eight to nine hours to travel the length of the Cowboy Trail by car and at least four days on horseback.

Reliving the past

There are about 30 ranches along Cowboy Trail that are open to visitors. Many offer working ranch vacations where visitors can learn to ride a horse and lasso a calf, or can join cowboys as they herd cattle to grazing areas. When night falls, they can relax beside a campfire and sleep in a guest room or log cabin.

Western legends

The history of the most famous outlaws comes back to life along this trail, where cowboys took refuge from the law, hit men and bounty hunters. In Saskatchewan, near the city of Moose Jaw, there are huge caves, ravines and steep outcrops for visitors to explore.

Over a century ago, these were the hideouts of bandits like Henry Borne, the biggest cattle rustler of the Wild West and leader of a group of more than 300 cowboys in the United States. It was also here than Harry Longabaugh, better known as the Sundance Kid, worked as a horse breeder before choosing the more lucrative career of train robber!

Finally, in the 1920s, the gangster Al Capone came here to vacation and do a bit of bootlegging as well.

Watch

The Bar U Ranch – National Historic Site – Longview, Alberta

A great story

On the ranch

(Public Library Network of Alberta)A Canadian cowboy and outlaw

In the latter part of the 19th century, the cowboy Sam Kelly was the most dangerous and most-wanted outlaw in Western Canada.

Originally from the province of Nova Scotia, in the East, he made a name for himself by helping two criminals escape from a jailhouse in the U.S. state of Montana. Sam Kelly was apparently in cahoots with the local sheriff, who arranged to send his posse out of town to help the Canadian cowboy do the job. Sam Kelly entered the prison, freed the two prisoners and escaped in broad daylight, with a smirk on his face.

He then teamed up with the legendary American outlaw Frank Jones. Together, they led a dangerous band of criminals. They set up camp in the caves of the Big Muddy Valley, which extends across the Canadian/U.S. border. For several months, they stole, killed and pillaged relentlessly.

The high outcrops and narrow ravines of the Big Muddy Valley, which today cuts across the Cowboy Trail, were ideal hideouts for Sam Kelly and his crew. From the high summits, they were able to spot the authorities from a distance and make a quick getaway.

Kelly finally turned himself in, but was acquitted because of a lack of witnesses.

Discover

Cowboy Association of Eastern Canada

The Cowboy Trail – Government of Alberta

Read

Watch

Horseback riding in Canada

Did you know?

Ranches were an economic driver in Western Canada

In the 1880s, the Parliament of Canada established a new policy on grazing leases (a land rental system that was very profitable for ranchers). As a result, the livestock breeding industry in Western Canada became very strong, even rivalling the logging sector.

Between 1880 and 1950, a number of ranches were established in the West, including the famous Bar U Ranch, in 1882. Nestled at the foot of the Rockies, this ranch is part of a group of vast ranches, including Cochrane, Oxley, Walrond and Quorn, which for years played a pivotal role in the economy of Western Canada.

These ranches were among the best managed in the world, and breeders came from as far afield as Argentina to learn the business. The farms were the size of small countries.

At the height of its activities in the 1920s, the Bar U covered 650 square kilometres and had 30,000 head of cattle.

It enjoyed an international reputation as a breeding centre for cattle and purebred horses, and was in fact the cornerstone of an even more extensive business empire that included smaller ranches, farms, meat-packing plants and flour mills.

Today Bar U is a national historic site open to the public and continues to be a successful cattle-breeding operation.

Tracing Aboriginal history

Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump

(UNESCO/Maureen J. Flynn)It is relatively difficult to reconstitute the history of Canada’s indigenous peoples in the periods prior to the arrival of European settlers 500 years ago, since they did not have writing and left few traces.

There are at least three major museums where visitors can retrace the history of Canada’s Aboriginal peoples and discover the origins of some of their traditions.

In Montreal, the McCord Museum houses close to 16,000 Native artefacts: over 8,500 archaeological objects (stone tools, potsherds) dating back to a period of 8,000 years before the common era up to the 16th century; and over 7,000 historical Aboriginal objects from the early 1800s to 1954, including clothing, accessories, headgear, domestic tools, baskets and hunting weaponry.

A second museum with a comparable collection is the Canadian Museum of History in Ottawa, Canada’s capital city. This is the country’s most popular and most visited museum.

One of the biggest Aboriginal museums

Finally, in Western Canada, right beside the Cowboy Trail and in the shadow of the Rockies, is a museum built into the major Aboriginal archaeological site of Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, which is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Indigenous peoples of the plains used the cliff for over 5,500 years to hunt bison. Hunting in groups, they would drive the bison from their grazing area about three kilometres west of the site, setting fires and waving blankets to guide them through rows of piled-up stones towards the cliff. They would then force the bison over the edge of the cliff, which is 10 to 18 metres high and 300 metres long. Those that fell were killed and processed on the spot, and their hides were tanned in a nearby camp site.

The deposits of bones and stone tools that have accumulated over the centuries at the foot of the cliff are sometimes over 10 metres deep.

The Aboriginals stopped using the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump in the 19th century, after their initial contacts with the Europeans.

An interpretive centre and museum have been built right into the ancient sandstone cliff.

Did you know?

Free-roaming bison have a life expectancy of 18 to 22 years, while those raised in captivity live 35 to 40 years.

(CBC News)Can people still go bison hunting in Canada? No! It is no longer possible to hunt bison in forests or on the plains. The world has significantly changed since the first Europeans arrived in North America. Back then, bison were plentiful; they ruled the grassy plains across virtually the entire continent.

From Mexico to Canada, there were an estimated 60 to 100 million bison.

At the time, bison were vital to the livelihood of Western Canada’s plains people whose economy revolved around hunting these animals that roamed the grasslands in massive herds. The hunters only killed the bison they needed for food and clothing, so the size of the herds remained stable.

However, at the end of the 19th century, after 300 years of hunting by whites, there were only 750 bison left on the continent—just a few small herds living in captivity on a Texas ranch and in a New York zoo!

Efforts were started to rebuild North America’s bison population. The remaining herds were transported to Yellowstone National Park where there were only a few dozen animals remaining, because of poaching.

Today, there are an estimated 350,000 bison in the United States. In Canada, there are only 12,000 wood bison. The largest Canadian herd lives far from cities and hunters’ guns in the Northwest Territories, in the Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary. Bison are also bred on the plains for human consumption. There are currently 250,000 bison in total in Canada.

By the numbers: 900 kilos

That is the average weight of an adult male bison in Canada—100 kilos heavier than a grizzly bear and 400 kilos heavier than a polar bear.

- Bison are the largest land mammals in Canada.

- Some bison can weigh over 1,000 kilograms.

- The head and forequarters are massive.

- Bison can reach a height and length of 2 and 3.6 metres, respectively.

- Both females and males have short, curved horns which they use in fighting to assert their status within the herd.

- Although they are herbivores, bison can attack humans if provoked or when they sense danger.

- They are generally considered as dangerous as bears.

- They run at speeds ranging from 50 to 75 kilometres an hour.

- They can trample and injure people, as has happened in some of Canada’s national parks.

- Free-roaming bison have a life expectancy of 18 to 22 years, while those in captivity live 35 to 40 years.

Forest adventure

A black bear climbing a tree in Yoho National Park, in Western Canada

(Alex Taylor/Parks Canada)Every year in Canada, close to 500 people get lost in the forest, often with fatal results, because of problems related to hypothermia.

If you plan on hiking in the forest, even along marked trails, it is important to check the weather forecast and to take along a GPS device, warm clothing, water, food, a first-aid kit, a fire starter, a flashlight and a knife.

A high proportion of people who get lost in the forest know the area. Hikers and hunters who get lost must stay calm and remember that the biggest dangers are unexpected falls and certain animals.

Bears are the most fearsome animals in Canadian forests. That is why it is important to always stay in a group: most bears will keep their distance if they sense the presence of several people.

Be very careful when walking near a waterfall or into the wind, because a bear might not hear you or pick up your scent.

Keep an eye on your dog!

Dogs often provoke bears, which could lead to an attack. Your dog might run up to you with a bear hot on its trail! That is why it’s important to keep your dog on a leash and at your side at all times.

If you meet a bear . . .

. . . don’t run. The bear can easily outrun you and if you run, you risk provoking it. Bears show their aggressiveness by shaking their head and growling. They can also bare their teeth and claws, snap their jaws, slap the ground with their paws, stare you down and flatten their ears. This is a bear’s way of saying, “Give me some space.” Back away slowly and talk softly, without ever looking the bear in the eye.

Watch

Enjoying the bounty of Canada’s forests with Aboriginal peoples (in French)

Pierre Le Royer, one of Canada’s first coureurs des bois. Photo taken in 1889.

(Album universel)A great story

Our ancestors, the coureurs des bois

From the 19th to the early 21stcentury, Canada was in large part developed thanks to the invincible coureurs des bois who travelled to the heart of the continent.

Without them, Europe would have been unable to engage in efficient, lasting trade with Aboriginal peoples. The intrepid coureurs des bois often acted as the direct representatives of colonial authorities and monarchs. However, in certain instances, the authorities treated them as outlaws, judging them to be too independent. Around 1750, for example, coureurs des bois who wanted to trade furs had to obtain costly official permits.

In 1750, coureurs des bois had to pay 1,000 pounds for a trading permit—the equivalent of $190,000 in today’s currency!

Those who traded without a permit were considered outlaws, and all of the furs had to be sold in New France or to the East India Company.

A tough life

The coureurs des bois travelled long distances transporting heavy bundles of furs. They portaged and endured extreme weather conditions. In addition, their profits declined year after year. Competition was fierce, because many settlers tried their hand at fur trading, even though it was illegal. The fur trade was also hampered by Aboriginal tribes who blocked access to waterways.

In the early 18th century, the lucrative beaver pelt market collapsed following a drop in European demand. From that point on, fur trading became a marginal economic activity, lagging far behind logging and wheat growing.

Read

Surviving in Quebec forests – blog (in French)

See

The fabulous stories of a coureur des bois (in French)

Did you know?

Yukon Quest, a sled dog race from Whitehorse, Yukon, to Fairbanks, Alaska, is considered the toughest race in the world. The challenge involves 1,600 km of ice and snow, and plenty of adrenalin!

(Radio-Canada/Jean-François Bélanger)About dog races

Sled dog races are run by teams of three to eight dogs. The drivers, usually called mushers, stand on the sleds. The team completing the course in the fastest time is the winner.

This sport can also be practised in the summer, with the dogs pulling sleds mounted on wheels.

Sled dog racing is a popular sport not only in North America, but in Europe as well. Along with the major Norwegian competitions, the Femundløpet and Finnmarksløpet, is the Grande Odyssée Savoie-Mont-Blanc—one of the largest sled dog races in the world, held in the French and Swiss Alps since 2005.

Dog sledding expeditions

Dog sledding is becoming an increasingly popular tourist draw in Canada. Éric Forget, owner of Le Chenil du Chien-Loup.

(Radio-Canada/Jean-François Bélanger)About 6,000 years ago, the ancestors of the Inuit arrived in Canada from Asia. Since then, the hiss of dog-drawn sleds on the snow has broken the silence of winter in Canada’s Far North.

Gee, gee . . . haw! OK, hike! Straight ahead!

Spurred on by the sound of your voice, a team of four or five dogs will pull you forward at astonishing speeds, taking you past mountains or along the winding course of a frozen river.

Dog sledding is a unique way to explore Canada’s great outdoors.

You’ll make frequent stops—well-deserved breaks for you, your guide and the dogs. Sheltered from the wind in the forest or beside a beaver dam, you can warm up with a hot beverage.

After a day of travelling through valleys and snow, and after eating a good hot meal, you’ll pitch your tent beside a hearty camp fire. Before going to sleep, you can marvel at the northern lights in the frozen silence of the night.

Not only for tourists

Dog sledding is not just for foreign tourists; it’s also fun for local outdoor enthusiasts looking for a new challenge. Driving a team of dogs is quite a workout!

On the trails of ancient dog sleds

During the gold rushes in the Yukon, around 1896, and in Alaska, starting in 1899, dog sleds rapidly became the main mode of transport, since they could reach places that were inaccessible to teams of horses. They were also a way to rapidly cover long distances across ice and snow.

In the new mining villages, where there were few recreational activities, dog team races were the main attraction. During the Yukon gold rush, the teams were usually made up of mixed breeds, but there were also teams of wolfhounds and hunting dogs.

In 1925, the small town of Nome on the western tip of Alaska was struck by a diphtheria epidemic. The ice and blizzards made it impossible for serum to be transported to the town by plane or boat. Running in relays, dog sled teams were able to cross hundreds of kilometres across ice and snow and reach Nome with the life-saving serum.

Each year, in Alaska, the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog race commemorates this event.

By the numbers: 30 km an hour

A sled pulled by frisky dogs sets off from the starting point at the Internationale des chiens de traîneaux Lanaudière, in Quebec.

(Radio-Canada)This is the average speed of sled dogs over distances of 40 kilometres or less in the snow.

Over longer distances, the average speed is between 15 and 20 kilometres an hour.

Even in poor weather conditions, such as blizzards, sled dogs can maintain an average speed of 10 kilometres an hour for several hours. Some dogs are capable of covering 150 kilometres in 24 hours.

Photo Album