Canada

By Boat

Introduction

Canadian Coast Guard Ship (ArcticNet)

Canada is one of the great maritime nations of the world. Eleven of the country’s 13 provinces and territories border at least one of three oceans: the Pacific, the Arctic and the Atlantic. Canada also has a vast inland sea, Hudson Bay, which lies north of the famous Great Lakes region.

It could be argued that Canada is mostly immersed in water. There are one million islands and three million lakes in the country, a world record. All this water facilitates circulation of 750 to 1,300 merchant ships daily, mostly during the summer months.

From November to April, most waterways are frozen.

In summer, Canada’s economy takes full advantage of numerous natural inland waterways. Some rivers are comparable in size to the Amazon, the Nile or the Mississippi.

The Fraser River, for example, flows for 1,370 kilometres. The Mackenzie, the longest river in Canada, totals 4,241 km in length. As for the St. Lawrence Seaway, it extends more than 3,000 km. All this helps explain why Canada holds 20% of all the fresh water on the planet.

The Great Lakes seen from space.

(Mark Alberts/Mongrel Media)A little geology

The Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River give Canada much of its shape. Seen from space, there is no doubt that the St. Lawrence estuary is the largest in the world.

The river and its estuary are in fact the result of a giant fissure on the Earth’s crust that emerged some 10, 000 years ago, when glaciers started melting.

The largest freshwater reservoir of the world

The Great Lakes were formed at the end of the last ice age, when a wall of ice 10 kilometers high withdrew to the north. It left behind many boulders and giant rocks and large amounts of melted water.

The Great Lakes could cover the 48 continental states of the United States to a depth of about three meters.

Did you know?

Georgian Bay, in the heart of the Great Lakes

(Radio-Canada/Yvon Thériault)Pollution in the Great Lakes

Over the years, the St. Lawrence Seaway and its network of rivers and waterways have attracted paper mills, metallurgical and chemical plants, automobile manufacturers and many manufacturing companies. Gradually, they have greatly polluted some water bodies around the Great Lakes.

Today, toxic heavy metals can be found in the entire food chain in and around the region. These pollutants are particularly harmful to beluga whales in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.

In 1980, an International Joint Commission by the United States and Canada examined water quality in the Great Lakes area and identified 42 sites of concern.

View

The Great Lakes, junkyard of the North. Radio-Canada Archives. (In French only)

A great story

Image of the Champlain Sea, a vast expanse of salt water that disappeared 10,000 years ago, shortly after the last glacial era, in the St. Lawrence Lowlands.

(Wikipedia)Why are there seashells in my garden?

Nearly a billion years ago, the site of the St. Lawrence Valley was occupied by a continental plateau as high as the one in Tibet.

At the end of last ice age, 12,000 years ago, retreating glaciers formed the Champlain Sea. This vast inland of salt water disappeared a little less than 9,000 years ago, giving way to the St. Lawrence River.

That is why some residents of Montreal suburbs often find small seashells when they dig their backyards.

Whale safaris in Canada

A whale in the North Atlantic.

(Environment Canada)Canada’s West Coast and Quebec’s shore are among the few places in the world where it is possible to see whales at the surface of the sea. Marine mammals are attracted by the large food reserves in the huge estuary of the St. Lawrence.

Measuring over 25 meters, the blue whale is the largest animal on our planet. It is a frequent visitor of the waters of the St. Lawrence, where the sea meets the mighty river.

During the warmer months of the year, many ports on the north and south shores of the Estuary and the Gulf of St. Lawrence offer daily excursions aboard powerboats.

In some places, the river is so deep near the coast, that it is often possible to watch whales from the shore.

Other Canadian waters are also rich in whales

For the past 20 years, whale watching has gained popularity in the steep hills of British Columbia’s West Coast. Whales can be seen diving at all times of the year in the North Pacific Ocean.

About 33 species of whales live in Canadian waters, 13 of which have been the subject of large-scale commercial fishing. In 1972, the federal government ordered a halt to all whaling operations based in Canadian ports. A moratorium on whale fishing took effect 1 January 1986. Cameras have since replaced harpoons.

Read

Invented by Canadians

An Indian canoe.

(Radio-Canada)Canoes crossing rivers and forests

For a very long time, the canoe was the main means of transportation of goods and people in Canada. In fact, most of inland Canada was first explored by canoe.

Until the arrival of the steam boat in 1820, this type of boat was the universal method of transportation. It was the “people’s car” for Native Americans and for white people. At the time, everyone knew how a canoe was built and how it should be repaired.

A recipe of the past

The “Canadian canoe” found in stores today looks very much like the original vessel created by Indian traditional methods. The material, however, has changed considerably.

Canoes used to be made from bark or hollowed tree trunks. Birch bark was the material of choice for traditional canoes in Canada. It is smooth, light, hard, durable and waterproof and can be found almost everywhere in the country.

The Canadian canoe features a slim profile, a wide flat bottom and sides that are slightly inclined inwards.

It takes eight to twelve trees to make a canoe, and one to three logs to repair one in the forest.

The birch panels of a typical canoe are sewn together with pine roots. The frame of the boat is usually made of cedar soaked in water, then bent into the shape of the boat. Finally, pine resin or spruce resin, applied with a hot stick, makes the seams waterproof.

The aquatic equivalent of the Ford Model T

Around 1750, French settlers built the first and largest canoe factory in the world. Mass production allowed builders to create a variety of basic models. It was at this moment that very long canoes were made, luxury models designed for affluent traders.

In the nineteenth century, the “top model” was 12 meters long and could carry six to 12 people, plus a load of 2,300 kg.

There was also a small “Canot du Nord”, or canoe of the North. Its wider body could accommodate five or six men and a cargo of 1,360 kg. It was used to navigate lakes, rivers and streams that were difficult to access.

Propelled by paddles, these canoes could cover a distance of seven to nine kilometers in one hour, at a rapid and steady 45 strokes per minute. Some canoes, carrying more people and fewer goods, could travel even faster, up to 140 kilometers in 18 hours.

In 2012, Dominique Liboiron, a French Canadian living in the Prairie province of Saskatchewan made a 5,000 km canoe trip from Saskatchewan all the way down to New Orleans in the U.S.

(canoetoneworleans.com)Did you know?

Each year, people participate in ice canoe races across the St. Laurence River, in Quebec City.

(PC / Clement Allard)Carrying a canoe on your shoulders

A canoe can be easily transported on the shoulders of a single person. Carrying a canoe between two rivers, through forest or grassland, is called portage. Of course, portaging a canoe is easier if two people are at hand.

There is a small town called Portage La Prairie, in the province of Manitoba.

Watch

Canoe believe it? Winter paddling is a growing sport in Quebec – CBC

By the numbers

From 1928 to 1971, Pier 21 was the main maritime gateway for immigrants.

(Ottawa Library)– 21

21 was the name given to a famous pier at the port of Halifax, at the edge of the Atlantic Ocean. Between 1928 and 1971, it was the maritime gateway for immigrants.

It was the Canadian “Ellis Island.

At the time, more than one and a half million immigrants entered Canada through Pier 21. Most came from Europe. The average length of their voyage was six to seven days.

Pier 21 also saw Canadian military troops leave the country to the fight in World War II. It is estimated that this pier played a decisive role in the personal or family history of 20% of all Canadians who are alive today.

Today, Pier 21 is a museum that focuses on the past, present and future of immigration to Canada. It attracts lovers of history and genealogy.

Discover

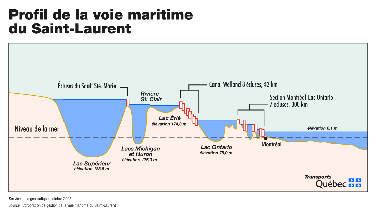

The St. Lawrence Seaway

The St Lawrence Seaway.

(Radio-Canada)The St. Lawrence River is the largest natural maritime pathway in the world. Thousands of giant cargo ships coming to North America from all over the world must sail it.

A river crossing fit for Gulliver

Opened in 1959, the St. Lawrence Seaway has been and still is at the center of North American trade.

It was created for ships that are 220 meters long, 23 meters wide and 35 meters high, with nearly an eight meter draft.

The first section of the Seaway is located in the St. Lawrence River. It is a series of canals and locks, five in Canada and two in the United States. In less than a week, ships can sail from the Atlantic Ocean to all major American and Canadian inland ports near the Great Lakes, almost at the center of the continent.

- About 4,000 ships pass through the St. Lawrence Seaway each year.

- Due to ice, navigation stops in mid-December and starts again in mid-March.

- Nearly 70% of vessels that use the channels are heading to a U.S. port.

- The St. Lawrence Seaway is 3,700 km long.

- About 36 million tonnes of goods go through this route each year. This is significantly less than the record year of 1988, when 66 million tonnes of goods were transported.

- Grains represent 40% of the total cargo.

Although the Seaway was mainly built by Canada, it is administered by Canada and the United States.

The beginnings of the Seaway

Navigation on the St. Lawrence River was a major challenge, at first for Native Americans and later for settlers arriving from Europe.

Until the eighteenth century, ocean vessels could only sail up to Quebec City. At that time, even small boats were not able to go further upstream, to Montreal, for example, because of rapids.

In 1700, the creation of a channel that bypassed the rapids brought the first improvements in transportation on the river. The construction of the Lachine Canal was laborious, expensive and did not end until 1825.

The creation of this canal required the opening of the largest construction site of the British Empire.

When completed, the Lachine Canal measured almost 14 kilometers, had six locks and a depth of only 1.5 meters. Thanks to the canal, Montreal would rapidly become the industrial metropolis of Canada.

We need to build more

In the late eighteenth century, interest about the creation of a deeper waterway on the St. Lawrence to the Great Lakes grew steadily on both sides of the border. Discussions between the U.S. and Canadian governments became animated.

In 1895, the two nations formed a Commission of waterways to explore the idea. Two years later, it declared itself in favor of the project. But little was done by the U.S., so Canada decided to spearhead on its own a series of small projects to widen certain sections of the existing waterway.

Until 1904, work was done on the Lachine and Welland channels, so that they could accommodate boats with a 4.3 meter draft. In 1932, Canada started work on another major section, this time in Ontario. These were the first steps in the development of the Seaway as we know it today.

Tensions between Canadians and Americans

By the early 1950s, U.S. and Canadian companies were exerting constant pressure on their respective governments to persuade them to dig a wider, deeper waterway.

World trade had advance at the speed of lightning during those post-war years and it required the transportation of goods of all kinds to feed the consuming needs of the growing North American population.

At first, the U.S. government did not want to pay for any modernization. Canada must absorb all the cost, it said.

Canada then threatened to develop the Seaway, but only on Canadian territory. If the Americans did not want to pay, they would have to go without a seaway. After hesitating, Washington finally agreed to share the cost with Canada, in 1954.

Labors of Hercules

In September 1954, work started on the new St. Lawrence Seaway. This required the flooding of vast areas, the expropriation of 260 square kilometers of territory and the disappearance of entire villages. Approximately 6,500 people were relocated to new homes, and not fewer than 550 homes were transported and fixed on new foundations.

In April 1959, the St. Lawrence finally became a “highway” between the Atlantic Ocean and the heart of the North American continent.

(Management Corporation Seaway St. Lawrence)

View

Queen Elizabeth officially opens the St. Lawrence Seaway – CBC

Watch

Visit of Queen Elizabeth II to Canada in 1959 as part of the official opening of the Seaway St. Lawrence.

Invented by Canadians

A ship waits for the opening of the locks in St. Catherine’s, Ontario.

(Mark Chambers)Lakers: vessels for a giant inland sea

Throughout the twentieth century, large vessels called lake freighters or lakers have plowed the five Great Lakes (Ontario, Erie, Huron, Michigan, Superior) and the St. Lawrence River, up to the Atlantic Ocean.

Nearly 150 lakers operating

Lakers can carry a million bushels of grain (27,000 tones) in a single trip. Wheat and other feed grains represent 40% of freight carried by Canadian lakers, followed by coal, iron ore and limestone.

These ships transport also iron ore from mines situated in Quebec and in the Labrador region of Canada. They bring the mineral to steel mills in the Great Lakes region, where American cars are made.

Nearly as long as the giant oil tankers of the Pacific Ocean, lakers are fitted with a shell almost as flat as a rowboat.

Among modern lakers constructed after 1970, the largest measure about 300 meters and are commonly called footers. They are too large to navigate rivers and streams, including the St. Lawrence Seaway, because of locks.

Boats built for the job

The long and flattened silhouette of these vessels allow them to carry bulk goods along a series of locks that are one-third narrower than the Panama Canal.

Lakers can remain in service as long as 50 years, largely due to the low salinity of the Great Lakes, which causes less corrosion than ocean water. In addition, the low water temperature provides excellent engine cooling. Several small lakers, dating from the early twentieth century, are still sailing.

The laker Richelieu on the St. Lawrence Seaway.

(Paul Island Cooledge/1000 Image)By the numbers

The Maid of the Mist can get very close to Niagara Falls. The first boat of this kind was commissioned in 1846.

(Canadian Press)– 2 million

This is the number of liters of water falling every second over the famous Niagara Falls, the most powerful falls of the North American continent. Every two seconds, they pour the equivalent of water contained in an Olympic swimming pool. That is 30 Olympic swimming pools per minute or 1800 pools per hour.

To enjoy this water to the point of almost touching it you can board the Maid of the Mist.

This ship, whose name evokes Ogiara, a character from Indian mythology, has been transporting passengers in the vortex that lies directly behind the falls since 1846.

Watch

Niagara Falls on the Maid of the Mist

A great story

Niagara Falls as seen by tourists from the city of Niagara Falls, on the Canadian side of the border.

(CBC)The day Niagara Falls stopped

On March 29, 1848, Niagara Falls mysteriously stopped flowing. The usual flow of water turned into a trickle. People flocked to observe the phenomena. Some saw it as a sign of the impending end of the world. The bravest made repeated crossings on the riverbed, leaping from rock to rock. They discovered a multitude of objects at the bottom of the dried up river: old rusty bayonets, rifles, tomahawks and other artifacts dating from the Canada-US war of 1812.

Others soon discover that upstream of the river water was blocked by the formation of an ice wall several meters high. Everything was sealed at the convergence of the Niagara River and Lake Erie, which prevented the water from going down the river.

About 48 hours later, on the night of March 31st, the ice gave way, and the river began to flow once again into the famous waterfalls.

Maritime tragedies

A screen of mist rising over Lake Superior, one of the five Canadian Great Lakes.

(Canadian Press)Despite modern technology (GPS, radar, etc.) and other conventional navigational aids located on the shores of Canada, the St. Lawrence River and its estuary remain one of the most dangerous waterways in the world.

Sandbars are numerous, and visibility is often limited, especially in winter, when ice can easily encircle boats and pierce their hulls.

In many places, commercial vessels over 100 feet (30 metres) must be guided by certified pilots. These security specialists are trained to navigate the changing waters, where the tides can exceed six meters high and strong currents swirl frequently in more than one direction.

Danger on the Great Lakes

Like a vast inland sea, the Great Lakes can also be dangerous for ships. They are the tomb of hundreds and hundreds of boats, mostly sailing ships that sank between 1750 and 1870, in storms or following fires and collisions.

The oceans that take our lives

Sable Island is home to about 250 wild ponies, protected from humans. They gallop on this crescent-shaped island that is 42 km long, but never larger than 1.3 km.

(CBC)In the Atlantic Ocean, 300 kilometers south of Halifax, capital of Nova Scotia, is the dreaded Sable Island. This area is nicknamed the “Graveyard of the Atlantic” because of its quicksand, formed by wind and currents. More than 350

Sable Island is also the home of wild horses. They landed there a little unwillingly, following a shipwreck or two more than 100 years ago. How do these animals and plants survive the waves, wind and isolation? Storms are frequent and violent.

Canada has had more than its share of shipwrecks and tragedies, both inland and along its shores.

The largest accidental explosion in history

What remained of downtown Halifax in the hours following the tragedy of 1917.

(Nova Scotia Archives & Records Management / Canadian Press)

The Norwegian ship Imo washed up on shore after the explosion of 1917. It had collided with the French vessel Mont Blanc.

(Nova Scotia Archives & Records Management / Canadian Press)Despite its small population of 400,000 people, Halifax is the largest coastal city in Canada after Vancouver. The bucolic capital of Nova Scotia, on the Atlantic coast, has one of the largest fishing ports in the world and the largest Canadian naval base.

For decades, Halifax was unnoticed from the rest of the world, until the sinking of the Titanic, in 1912. However, the city’s «15 minutes of fame» occurred five years later.

In Dec. 6 1917, Halifax Harbor was the scene of the most violent accidental explosion in human history.

On a very foggy morning, a Norwegian ship collided with a French vessel loaded with explosives. About 2,000 people died and 9,000 were injured.

World War I was still in full swing, and many great vessels gathered at the Port of Halifax before starting their long voyage to Europe. Convoys of ships carrying American and Canadian military equipment of all kinds left Halifax on a daily basis.

In a hurry to leave

On the morning of December 6, 1917, a Belgian relief ship called Imo was anchored in the harbor. Its captain was upset that an inspection the previous evening had forced him to postpone his departure for Europe.

Farther offshore, the French steamer Mont Blanc waited for official permission to enter the port. Its captain, Aimé De Medec, was worried, and for good reason. His boat was loaded with thousands of tons of acid, TNT, gun cotton and benzene.

Because of its ammunition cargo, the Mont Blanc was a true floating bomb. It was especially vulnerable because German submarines sometimes wandered off near the port’s entrance

At 7.30 a.m., the Mont Blanc was finally starting its slow entry into the port, when the Belgian ship Imo weighed anchor. Fog had forced it to take wrong side of the channel. Unknowingly, it headed towards the Mont Blanc. When both vessels saw each other, it was too late. Despite a series of frantic shrill whistles, the collision was inevitable.

A man sacrifices his life to save 700

On the shores of Halifax, thousands of spectators gathered to witness the accident. Factory workers, longshoremen, mothers and children rushed to places that would allow them to better see what was happening. They had no idea of the impending danger.

Among the victims, was telegrapher Vince Coleman. From the window of his small office in downtown Halifax, he saw the two ships collide and ignite. Unlike others, knowing what these ships could hold, he considered the situation very dangerous. He had only one or two minutes to act.

Rather than flee, Coleman remained at his post. By telegraph, he alerted a train which was heading directly to the port of Halifax, carrying 700 passengers. It was 9.05 a.m.

On the other side of the hill, the train driver picked up the message and stopped his locomotive.

At 9.06, the worst man-made explosion before the atomic bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki devastated Halifax. The blast was heard up to 420 kilometres away.

To this day, the Halifax Explosion remains the worst man-made disaster that has ever occurred in Canadian territory.

Read

Tragedy of December 6 in the port of Halifax. Canadian War Museum.

History Canada: Dec. 6, 1917: WWI strikes Halifax

Watch

The Halifax Explosion – Documentary

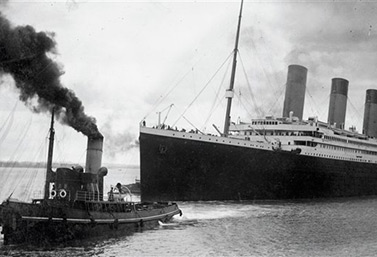

How the Titanic nosed down

The Titanic sailed from Southampton on April 10, 1912.

(AFP / Southampton City Council)In 1912, newspapers reported that the RMS Titanic, a transatlantic British vessel owned by the White Star Line, was truly invincible. The Titanic was also the most luxurious and largest liner ever built.

Its success was short-lived however. On April 15, 1912, it hit an iceberg off the coast of Canada and sank 650 km southeast of Newfoundland.

Between 1,490 and 1,520 people died in the wreck, which makes this event one of the greatest maritime disasters in peacetime. It was also very publicized at the time, especially because it caused the death of several well-known millionaires.

This tragedy highlighted the shortcomings in evacuation procedures and the insufficient number of lifeboats on all transatlantic boats at that time.

The lifeboats on the Titanic could carry 1,178 people, but there were 2,200 people on board. Most lifeboats left the Titanic half empty. Only 2 of the 20 boats were full.

The tragedy of the Titanic, minute by minute

- At 23.40, the Titanic hits an iceberg off the coast of Newfoundland as it progresses at over 40 km/h. It has already traveled more than 2,700 kilometers on her journey. The shock slightly vibrates the ship metal plates. Rivets are torn and an opening erupts along a few meters into the hull, below the waterline.

- At 0:15, the Titanic sends its first distress call.

- At 0:25, the captain gives the order to begin the evacuation of women and children in the lifeboats.

- At 0:45, the first boat carrying 28 passengers leaves the Titanic. It could have accommodated 65.

- At 1:40, the ship sends the latest in a long series of flares in the sky.

- At 2:05, the last two lifeboats are put to sea.

- At 2:17, the Titanic sends its ultimate radio SOS, as the water reaches the radio booth.

- At 2:17, the orchestra stops playing. Shortly after, one of the four boat chimney collapses.

- At 2:18, the lights of Titanic flash, then turn off.

- At 2:20, the ship breaks in two. The front of the ship sinks, but the rear portion floats for a few moments.

- At 2:22, the rear part of the Titanic is swallowed. The water temperature is 2 ° C.

Read

The story of the Titanic. Government of Nova Scotia.

Canada history: APRIL 15, 1912, Titanic disappears off Newfoundland – RCI

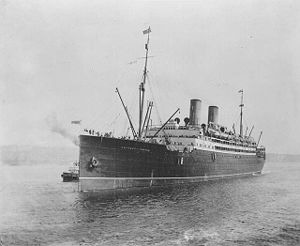

The Empress of Ireland

A shipwreck that took only 14 minutes

The Empress of Ireland

(Archives)The Empress of Ireland was a transatlantic vessel belonging to the Canadian Pacific Railway company, better known for its passenger trains. At the time, the company operated the world’s largest network of transportation and communication. Since January 1906, the Empress had travelled regularly between Quebec, Canada and Liverpool, England.

The Empress of Ireland and its twin, the Empress of Britain, were the largest, most comfortable and fastest vessels of the Canadian fleet in service on the Atlantic Ocean.

The Empress Class liners were of medium size, 168 meters by 20 meters, with nothing of the luxury that could be found on other liners that competed in the New York-Europe route. However, it provided a comfortable journey to people travelling between the UK and Canada at a much reduced cost.

The last moments of the Empress of Ireland

On May 29th, 1914 at 16.30, the Empress of Ireland left the port of Quebec. Nearly nine hours later, it would sink into the St. Lawrence River, a few kilometers from town of Rimouski. This would be the largest shipwreck in the history of Canada.

The ship was in its 192nd voyage across the Atlantic. It was the first time it was managed by Captain Henry Kendalla.

On the night of May 29th 1914 at 1.55, the ship was progressing rapidly into the mist, when it hit a Norwegian coal ship on the starboard side. The Empress of Ireland flipped quickly to the side, making rescue maneuvers impossible. One single lifeboat was released from the vessel. It sank in only 14 minutes.

Due to the swiftness of the sinking, the inability to use the lifeboats and the temperature of the water in the St. Lawrence River (0C to 4C throughout the year), only 465 of 1,477 people aboard survived.

This wreck made fewer victims then the Titanic (1,513 dead out of 2,208) and the Lusitania (1,198 out of 1,257). However, the proportion of deceased individuals was greater; only 12 people survived the tragedy.

Since 2009, the site of the sinking of the Empress of Ireland is designated a National Historical Site of Canada.

Discover

History: 29 May, 1914 : Canada’s worst maritime disaster – RCI

The Edmund Fitzgerald

The giant ship engulfed by the Great Lakes

The SS Edmund Fitzgerald on the St. Mary River in May 1975, six months before the sinking that killed 29 people on board, during a devastating storm.

(United States Army Corps of Engineers)The SS Edmund Fitzgerald was an American cargo vessel active in the Great Lakes region between Canada and the United States. It carried mostly Canadian iron ore to facilities of the U.S. auto industry. At the time of its inauguration, June 8th, 1958, it was the largest ship to sail the Great Lakes.

The Edmund Fitzgerald was a 222 meter-long giant iron and steel monster that was considered virtually indestructible. It was commanded by a very experienced captain. However, it suddenly sank during a storm on an autumn evening, in Lake Superior, killing the crew of 29 people.

This tragedy is still told from father to son and affects many Canadians.

One of English Canada’s greatest songs, The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald, immortalized the sinking. It was composed by Gordon Lightfoot, one of Canada’s most famous singers.

A tragic and mysterious end

On November 10, 1975, the SS Edmund Fitzgerald was en route to the U.S. city of Detroit, Michigan. It had on board a cargo of just over 26,000 tons of iron ore. A second giant freighter, the Arthur M. Anderson, followed a few kilometers behind.

Both vessels had started the crossing of Lake Superior when a fierce winter storm erupted. To this day, the storm is considered one of the most important meteorological phenomena of the twentieth century in North America. The two ships soon faced waves more than 7 meters high and winds of 125km /h. To avoid the storm, both vessels changed their path, seeking shelter near the Canadian coast.

- At 19:10, the radio operator of the Edmund Fitzgerald sent a final message to the Coast Guard: “We are holding our own.”

- At 19:20, the Arthur M. Anderson could no longer see the Edmund Fitzgerald on its radar. It tried to contact the ship, but received no response.

- At 20:32, sailors of the Arthur Anderson informed the U.S. Coast Guard of their concerns. Accompanied by another ship, they went in search of survivors.

The investigation stalled, then failed

The wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald was spotted two weeks later, broken into two main sections. It was embedded in the mud under 160 meters of water.

Several theories have been proposed to explain the accident: rogue waves, shoaling. The most likely hypothesis is that a partly closed hatch gradually let water in as the giant waves pounded the vessel, until its hull broke. The exact cause of the sinking has never been determined.

Listen

Hear Gordon Lightfoot’s song and watch images of the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

Watch

The end of the Edmund Fitzgerald

Adventure sailing on the Great Lakes of Canada

Loading cargo on a Great Lakes Laker

The Ocean Ranger

Platform destroyed by storm

On the night of February 15, 1982, during a storm, the Ocean Ranger oil rig sank beneath the waves. Eighty-four men perished in the tragedy.

(CBC Digital Archives)At the time of the tragedy, the Ocean Ranger was the largest semi-submersible oil platform in the world drilling offshore. Property of Mobil Oil of Canada, it was located in the Grand Banks, 267 km east of St. John’s, the capital of Newfoundland.

On the night of February 15, 1982, a terrible storm arose. Winds of 145 km/h blew amid 18 meter-high waves. All 84 members of the crew would perish beneath the waves.

A catastrophic chain of reaction

When the storm hit, seawater was projected into the ballast control room through a small broken portlight. This caused a power outage. With the ballasts no longer functioning, the platform lost its stability in the raging sea and tipped over in a matter of minutes.

This tragedy was caused by a series of small events not serious in themselves. Without appropriate intervention, their combined effects quickly reached catastrophic proportions.

Following the tragedy, there have been major changes to regulations and procedures for crew training and safety at sea everywhere on the planet.

View

Navigation in ice

Kaeble V.C. is the second of nine vessels being currently built in Halifax for the Canadian Coast Guard.

(CBC)At least six months per year, the Canadian Coast Guard and its icebreakers hurry along the Canadian coast and guide ships trying to advance in frozen waters.

In winter, severe weather conditions plague Canada’s three oceans (the Atlantic, the Pacific and the Arctic) and pose serious challenges to ice-fighting vessels.

In early winter, the Atlantic Ocean is particularly turbulent. Ice that is two meters thick and waves that are six meters high are very common on the north-east coast of Canada, from Newfoundland to the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

The bad side of the St. Lawrence River

Navigation in the St. Lawrence creates special dangers when large ice sheets consolidate and stand in the way of ships.

Canada has the longest coastline in the world (about 244,000 kilometers), but it is along a few thousand kilometers of its eastern coastline eastern coast that the Canadian Coast Guard is the most active.

The beautiful Canadian icebreakers

Canadian icebreaker CCGS Louis S. St-Laurent (in the foreground), joins U.S. Coast Guard ship Healy.

(Kelly Hansen)Three countries are known for their icebreakers: Norway, Russia and Canada.

While Norway’s fleet is the most modern, Russia’s icebreakers are the most powerful.

Canada operates about one-fifth of all icebreakers in the world: 14 are owned by the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) and two by mining or oil companies. CCG icebreakers are classified as follows: heavy (2), medium (5) and light (7).

The most powerful Canadian icebreaker is the Louis S. St-Laurent. With a capacity of 14,000 tones, it is slightly smaller than the four most powerful Russian nuclear icebreakers in service.

No icebreaker operating in Canada is able to penetrate Arctic waters during the harsh winter which lasts from November to May.

Icebreakers tailored to our needs

Canadian icebreakers are tailored to specific needs. They ease transportation on lakes, river mouths and the sea, they keep the St. Lawrence Seaway channels open and they promote the supply of goods in the Arctic.

Global warming in the Far North and the future of icebreakers in Canada

Since the 1990s, growing concern about the rapid melting of the polar ice cap and debates surrounding Arctic sovereignty have drawn attention to the fact that this region of Canada lacks adequate means of transport.

Icebreakers are at the heart of the new development strategy in Canada’s North. Over the next years, the Canadian Coast Guard will renew its fleet. Smaller or older vessels will be replaced by models that are more powerful and have greater range.

Watch

CCGS Louis S. St-Laurent is the largest and most effective icebreaker of the Canadian Coast Guard.

Did you know?

The Canadian icebreaker Amundsen – Government of Canada

The CCGS Amundsen, Canada’s best known icebreaker

Since its inauguration, the CCGS Amundsen has played a major role in the revitalization of Arctic Sciences in Canada. Because of its research facilities and scientific equipment, the Amundsen has become the mobile platform of Canadian researchers and their international collaborators.

The CCGS Amundsen icebreaker is the first research vessel that can conduct winter expeditions in the Arctic.

Invented by Canadians

CCGH Sipu Muin is a heavy and powerful hovercraft that performs icebreaking and search and rescue missions in The St. Lawrence River, in areas with difficult access for icebreakers.

(Canadian Coast Guard)The hovercraft ice breaker

Since the 1970s, Canada has been a pioneer in the use of hovercrafts that act as icebreakers on rivers.

Designed by Canadians, they operate by creating a cushion of high-pressure air between the hull of the vessel and the surface below. They gather enough speed to get on top of the ice and push forward a wave of pressure similar to that produced by conventional boats when moving quickly on the water.

Ice cover is rigid. This wave of pressure introduced under the ice surface makes the ice break.

By maintaining a good speed, the pilot of a hovercraft icebreaker is able to maintain a wave under the ice on a distance of several kilometers.

Given the vulnerability of their cushions, or skirts, hovercraft icebreakers can only be used on certain types of frozen surfaces.

They are mainly used during the spring months for ice breakup. They are also very good at preventing flooding and reducing the possibility of ice jams.

A great story

The Amundsen makes its way in the Saguenay River, Quebec, at a temperature of – 30 C.

(Jacques Boissinot / Canadian Press)Canada’s icebreakers, in service for over 100 years

Between 1876 and 1899, Canada built three small ferry icebreakers. They were put into service in the area between mainland Canada and one of its new provinces, Prince Edward Island.

In 1900, the first true Canadian icebreakers came out of the shipyards, the Champlain and the Montcalm. With names evoking French Canadian heritage, they were first used in the province of Quebec. Their mission was to break the ice walls and ice jams which, at the time, caused floods every year in the narrowest passages of the St. Lawrence.

Icebreakers were used for the first time in the Canadian Arctic, in the 1920s. Their task was to supply Aboriginals and remote communities with goods and services during the short summer season. Canada also used these vessels to document and make credible its claims of sovereignty over the Northwest Passage.

Over the next decade, more powerful icebreakers would be needed to open the northern port of Churchill, in order to ship grain to Europe.

Discover

Canadian icebreaker on an Arctic research expedition. Laval University.

The Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage

(Wikipedia)To bypass the Suez and Panama Canals

Across the globe many have dreamed of a navigable corridor that would cross the Arctic. Due to melting ice, the passage of the Northwest could become, in a relatively near future, a more economical route for the transportation of goods than the Panama Canal, for example.

Currently, giant cargo ships from East Asia have difficulty delivering their goods to the North America’s East Coast. Goods are first unload on the West Coast and then transported east by rail or truck. Another option is to travel even greater distances, crossing the Indian and Atlantic oceans to reach the East Coast.

The Northwest Passage would subtract up to 7,000 km on most trips, without having to transfer goods from one means of transport to another.

For the moment, the Northwest Passage is still impractical.

A distant dream begins

Researchers from the Department of Transport of Canada believe that, despite the melting ice, the conditions are still too unpredictable to allow regular commercial activity along the Northwest Passage.

Scientists from Environment Canada are of the same opinion. The complexities of ocean currents, the presence of large areas of ice that are attached to the mainland and the variability of sea-ice conditions from year to year make the Northwest Passage unattractive in the short-term. There are still very few port facilities in the Canadian Arctic and very few emergency services in case of a tragic event.

Cruises are a little more fun

Between 1906 and 2008, about a hundred trips were made in the North, most of them for military surveillance or mineral exploration. In 2017, in a single year, 23, mostly recreational boats, made the crossing, which is attracting a growing number of countries. Merchant ships transiting between Europe and Asia would save 7,000 kilometres with this route. That said, the cruise tourism sector is getting ready to invest in the region.

In fact, Canadian cruise ships have been increasingly active in the North. Using former Russian icebreakers or ships with reinforced hulls, cruise companies want to exploit the tourism potential of the legendary Northwest Passage.

Ferry across Canada

A ferry on British Columbia’s West Coast, not far from Vancouver.

(Darryl Dyck / Canadian Press)The largest ferry companies in the world are SeaLink (Europe), Danish State Rail, Washington State Ferries (USA), and the British Columbia Ferry Corporation (Canada).

Ferry operations could be profitable in a country like Canada, where seven million people, more than 20% of the population, lives in coastal areas.

Canadians, ferry experts

Over the past 35 years, bridges in Canada have often taken over the duties of ferries. However, two major ferry services still operate in salt water in the country.

The BC Ferry Crown Corporation in British Columbia offers trips along the Pacific. It has 35 ferries with a capacity of 27,000 seats that can accommodate a total of 22 million passengers annually, and serves 47 routes along the coast. It operates some of the busiest ferry ports in the world.

The company also owns four large dual propulsion ferries. They can carry 1,500 passengers and 360 cars each, spread over three decks. The term “dual propulsion” refers to the fact that propellers are attached to the stern and the bow of the boat, thus avoiding the need to rotate the ship into position at every docking.

At the other end of Canada, on the Atlantic coast

The old ferry Smallwood Marine Atlantic travelled from Newfoundland to Nova Scotia for 21 years.

(CBC News)Crown Corporation Marine Atlantic S.C.C. has the most diverse fleet, operating 18 vessels on maritime routes between Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New-Brunswick and the U.S. state of Maine.

Some of its fastest ferries are only 30 meters long. Other ferries are 148 metres long and can carry the equivalent of 39 freight train cars. There are also giant ferries that accommodate up to 1,100 passengers and their vehicles (automobiles, trucks and tractor trailers).

Others commute between 100 small ports in Newfoundland and Labrador, some of which have no other connection with the outside world.

Invented by Canadians

The modern ferry

The largest ferries of our time use a rolling system, which allows loading and unloading vehicles in a much shorter time, by the rear and bow doors.

Although Scandinavians claim to be the inventors of these ferries, the very first ferry with a rolling deck was the Canadian Pacific’s Motor Princess, launched in 1923 in Esquimalt, British Columbia.

This boat ended its long career with the British Columbia Ferry Corporation in the 1970s, under the name Pender Queen.

A great story

The Blue Nose, the world’s fastest schooner

Stamp collectors consider this stamp published in 1929 one of Canada’s finest.

(WR MacAskill)After World War I, Canadians found to their surprise that they had the fastest yacht in the world, the Blue Nose.

In 1920, after a season of cod fishing on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, the Nova Scotia schooner became famous when she won a race off-season between fishermen from the Maritimes and those of New England, in the United States.

For the next 17 years, no other boat could beat the Blue Nose

Afterwards, the famous yacht appeared in various international meetings. She represented Canada at The Chicago World’s Fair, in 1933. In 1935, she was in England for King George V Silver Jubilee.

The Blue Nose was so popular that in 1929 the Canadian government issued a stamp in her honor. It became a classic. Reissued in 1982 and 1999, the stamp shows the Blue Nose in full sail.

Fishing schooners became obsolete during World War II. In 1942, the Blue Nose was converted to a freighter in the Caribbean. In 1946, she struck a coral reef and sank near the coast of Haiti.

All Canadians know the Blue Nose. Since 1937, they can see it on all 10 cent coins.

We can also see the Blue Nose in all licence plates in Nova Scotia.

Today, we can admire a perfect replica of the famous yacht, the Blue Nose II. Every summer, it visits several ports in the country and revives the pride of Canadians who for 17 years owned the fastest sailboat in the world.

Read

BLUENOSE II SCHOONER – NOVA SCOTIA’S FAMOUS TALL SHIP – Nova Scotia’s website

Photo Album

Watch

The majestic Canadian Great Lakes.

Watch

Halifax Harbor.