Allen Rozon lives by his blades.

And the Abitibi native hopes to teach others to do the same.

Rozon is a full-time bladesmith who moved to Montreal about a month ago after travelling the world to learn his craft.

He has set up shop at Les Forges de Montreal, a non-profit smithy located in an old pumping station near the Lachine Canal in the old industrial heart of Montreal.

“A lot of people try teaching themselves,” Rozon said, taking a smoke break after helping to teach what he described as one of the most challenging blade-making workshops of his career. “And I’m a big fan of getting a really good teacher and developing at least a base before you go off and develop bad habits and make them part of your daily work.”

(click to listen to the interview with Allen Rozon)

ListenReviving an ancient craft

The place to do it in Quebec is Les Forges de Montreal, Rozon said over the din of hammers as students put finishing touches on their work.

“Les Forges de Montreal is essentially a facility whose focus is preservation of blacksmithing and bladesmithing techniques from around the world,” Rozon said.

Rozon has partnered in this mission with Les Forges de Montreal founder and head blacksmith Mathieu Collette.

“He’s an actual fully-apprenticed blacksmith who went to France to get his apprenticeship completed, he spent four years doing that,” Rozon said. “He came here, established this place and I am the latest piece in that puzzle.”

Rozon, his face covered in black soot from hours spent in the smithy, said has been learning the art of blade-making for 15 years but it’s only in the last five years that he has been able to devote himself to the art full-time.

The draw of red-hot iron

It all began with Rozon looking for an artistic outlet. He tried out painting and sculpting at first until he discovered blacksmithing and fell in love with the craft.

“I had a corporate job and what I would do is I would work and all my vacation time would be dedicated to this stuff and it if weren’t for that, I would quit the job and go for an extended travel and just find a new job when I came back, when I run out of money,” Rozon said.

Working for an advertising agency, Rozon said he yearned for something “real.”

“I was the smoke and mirrors guy, I was the strategic mind behind some of the ideas that made you buy stuff you don’t need and didn’t last,” Rozon said.

Fascination with blades

He wanted to be involved with something more tangible and lasting, Rozon said.

“In the corporate world, none of the work I did had any legacy to it, so I’d work on something unexciting and the next year, even less than that, it would be an idea that evaporated, lost in the noise,” Rozon said. “Making a knife, if I do it properly, will actually last longer than I ever will.”

Rozon said he makes all kinds of knives – from performance culinary knives, hunting knives, to pocket knives – with most of his creations heavily influenced by the Japanese style where he learned the craft.

“There is something about blades, it’s a geometry, it requires a really fine eye, it requires a tremendous amount of patience,” Rozon said. “A blacksmith can make a knife, but when a blacksmith makes a knife, you can tell that it’s a blacksmith that made the knife. The difference between a blacksmith making a knife and a bladesmith making a knife is the fit and finish, it’s the quality of the piece, it’s the time spent, it’s the thought put into the materials you’re using.”

Unbroken bladesmithing tradition

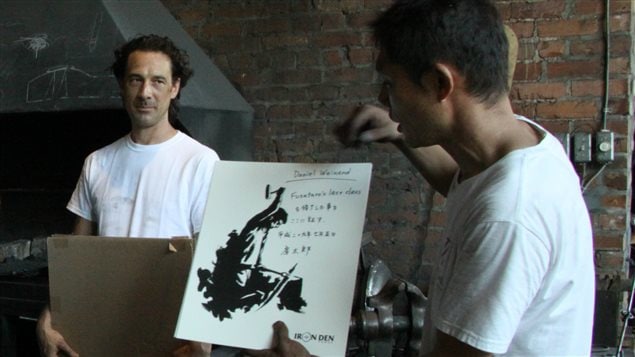

In about 2010, Rozon partnered with master Japanese swordsmith, Taro Asano, who goes by his swordsmithing name Fusataro.

Fusataro, 41, who’s been making traditional Japanese, swords, daggers and knives for 20 years, is one of rare masters who leave Japan to teach courses all over the world.

Japanese swordsmithing is the only bladesmisthing tradition that is unbroken to this day, Rozon said.

“For instance, he [Fusataro] learned from his master and his master learned from his master, and they can go down 25 generations,” Rozon said.

Together, Rozon and Fusataro decided to experiment with various forms of workshops to pass on this tradition.

“Half the experiment was to allow people to learn from a guy like him that’s unique the world over,” Rozon said.

The other motivation was to show how difficult it was to make a good blade, he said.

“Most people walk in thinking that they are going to make a full-length blade and they soon realize the difficulties in actually performing the work,” Rozon said.

It takes at least 10 years of hard work for a student to understand and master all of the steps involved in making a traditional Japanese sword, Fusataro said.

Getting into the right mindset is the most difficult thing in learning the art of blade-making, he said.

“If you’re greedy or have too much ego, you cannot make a blade,” Fusataro said. “You have to be pure or innocent in front of the steel or fire.”

Last course for foreseeable future

In fact the 10-day intensive course , which ran from June 26 to July 5, at Les Forges de Montreal was so hard for both students and instructors that this is the last time they will be offering the blade-making workshop, Rozon said.

But for Ivan Savchev, a Montreal blacksmith who now teaches an introductory blacksmithing course at Les Forges des Montreal, this was an opportunity he could not to miss despite the $6,000 price tag for the workshop.

“It was a lot of work, it was gruelling but I think it’s really fun, it was a really steep learning curve,” Savchev said, holding a piece of unfinished blade that he had forged from a special tamahagane steel provided by Fusataro to each workshop participant. “Essentially, I decided to start as if I knew nothing because that is how you must almost do it.”

(click to listen to the interview with Ivan Savchev)

ListenSavchev had to learn how to work with charcoal instead of the usual mineral coal used by blacksmiths in North America and Europe, he also had to learn to work with tamahagane, a porous, almost sponge-like material that’s turned into blade steel by a laborious process of repeated heating, folding, and welding.

“This started as two kilograms of tamahagane and it now weighs about 250 grams,” Savchev said displaying the Japanese-style knife blade he made. “That’s actually not as crazy as it sounds because you have something like seven out of eight loss ratio. You need eight kilograms of tamahagane to make a one kilogram katana blade.”

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.