Diamonds – the darker side of prosperity

SOMBA K’E/YELLOKNIFE, Northwest Territories – While prosperity brought by the diamond industry in the Northwest Territories has lifted thousands of families out of poverty, it has left some even worse off, struggling with crippling debt and substance abuse, says Arlene Haché, former executive director of the Centre for Northern Families in Yellowknife.

SOMBA K’E/YELLOKNIFE, Northwest Territories – While prosperity brought by the diamond industry in the Northwest Territories has lifted thousands of families out of poverty, it has left some even worse off, struggling with crippling debt and substance abuse, says Arlene Haché, former executive director of the Centre for Northern Families in Yellowknife.

Haché said many people were simply not prepared to deal with the sudden prosperity brought by well-paying jobs when the diamond exploration and mining boom started in the Northwest Territories in 1991, after geologists Chuck Fipke and Stewart Blusson discovered diamonds in the tundra, in the Lac de Gras area, about 310 kilometres northeast of the territorial capital Yellowknife.

|

Links to our series on diamond mining in the Northwest Territories: Canada – a diamond mining superpower Diamonds fuel the Northwest Territories’ economy Social ills keep many on the sidelines of NWT’s diamond boom |

“When you go from poverty to lots of money, you really want to live like other people have lived for a long time: so you want cars, you want houses and you want what everyone else has,” Haché said, speaking from her office in a downtown Yellowknife house, converted into women’s shelter. “And in fact people were so excited to get jobs en masse in communities, that in some communities people who sell cars would set up shop right in the community. It was quite interesting seeing communities all drive the same sort of trucks.”

However, even short employment disruptions such as temporary mine closures have thrown many families in crisis, because they hadn’t planned for days when they might lose their job, Haché said. Now, many are forced to look for help at the centre.

“For example we have a family with ten children, they bought a house, they got $50,000 from our government to buy that house, they bought vehicles, they bought furniture and all of that is gone in a flash,” Haché said. “Except now they are hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt that they didn’t have before.”

Many people didn’t know how to manage debt that they had taken on, because they thought that their jobs would last them forever, Haché said.

“Now, we’re seeing the downside of that, we’re seeing families who are losing everything and just wanting to move back to their small communities and just ignore all the debt they’ve incurred and turn a blind eye to that, because they just don’t know how to cope with it, how to manage it,” Haché said. “Except now they have people harassing them to pay their bills and to come up with money that they just don’t have.”

Sudden prosperity fuels old problems

The sudden prosperity brought by well-paying diamond mining jobs has accentuated some of social problems that existed long before the diamond mines arrived, said Roy Erasmus Jr, president and CEO of Det’on Cho Corporation, the economic development arm of the Yellowknives Dene First Nation.

Substance abuse and gambling have increased in aboriginal communities because of the easy access to cash, he said.

“We have a lot of people that come from shift work that have a lot of cash in their pockets and that’s supposed to be a good thing,” Erasmus said. “But when you have people who haven’t been used to having a lot of cash and handling cash, and managing cash, all of a sudden having a whole pocketful of cash, things can get a little bit out of hand sometimes.”

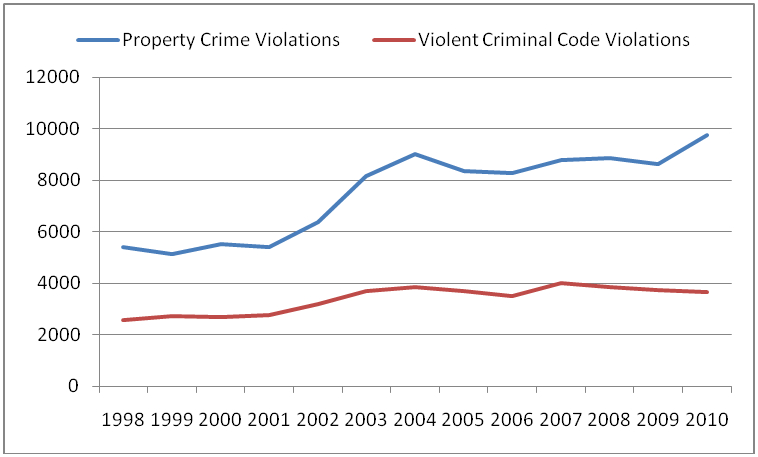

Crime statistics compiled by the territorial government between 1998, the year the first diamond mine started operations, and 2010 support many of these observations.

Between 1998 and 2010, there has been a 43-per-cent increase in the number of violent crimes reported in the territory, according to government statistics. There has also been a 65-per-cent increase in impaired driving incidents in the same period. There has been a 155-per-cent increase in the incidents of cannabis possession violations and an almost four fold increase in the number of cocaine possession violations.

Officials at all three diamond mining companies in the Northwest Territories – BHP Billiton, Diavik Diamond Mine and De Beers – said they each have special programs and trained social workers to help employees deal with financial and social problems. The mining companies have also invested millions on various social and educational programs in aboriginal communities – everything from building community centres to encouraging reading.

Shift work hard on mining families

Another factor that has been negatively affecting many northern families is the shift work at the mines, Erasmus said. Most miners work in two-week shifts: they’re flown to the isolated mine camps for two weeks and then spend two weeks with their families.

Another factor that has been negatively affecting many northern families is the shift work at the mines, Erasmus said. Most miners work in two-week shifts: they’re flown to the isolated mine camps for two weeks and then spend two weeks with their families.

“If you have a family member or a spouse that is working up at the mine, you’re essentially a single parent for the time when your spouse is away,” Erasmus said.

The children feel the impact as well, Erasmus said.

“When mommy or daddy comes home, whether good or bad the kids are impacted,” Erasmus said. “They stay up late when mom or dad comes home because their happy to see their parents, their routine gets a little bit disrupted.”

Franky Nitsiza said he credits his work at BHP Billiton’s Ekati mine with providing better opportunities for his family and his two children. But he said it’s a difficult balancing act.

“There are a lot of sacrifices,” Nitsiza said, “you have to be balanced, you have to make money to support your family, make a living for your kids and have a family life.”

Nitsiza said his two children, 6 and 2, miss him a lot when he leaves for his shift.

“It’s harder for me too when I leave, right? I don’t want them to see me leave in the morning, it takes a couple of days to get used to,” Nitsiza said.

And it’s family time he cannot make up no matter what he does when he comes back for his two-week stay at home, Nitsiza said.

“Loss is a loss, right?” he said. “It’s world living I guess – to sacrifice, to make money and make better living for your kids and family.”

Nitsiza said working at the mine has also meant that he had to give up on some of the traditional activities.

“I don’t trap anymore, trapping takes two months out of the community, out on the land, but now two weeks at home is just too short to trap,” Nitsiza said. “So what I do is, I go for three days caribou hunting or a little ice fishing, but not too often.”

Nitsiza said he hopes all these sacrifices will pay off in the long run by providing him with stable income and a pension.