Applying lessons learned to future Arctic fishery

While the possibility of fishing in the central Arctic Ocean – the world’s last untapped fishing area – excites many people in the fishing industry, marine conservation groups want robust rules set up before anyone is allowed to drop their nets into the sea, says Josh Laughren, executive director of Oceana Canada.

“We are concerned about how we look at exploiting that resource, which hasn’t been exploited before,” Laughren said. “Before anything goes ahead we want to make sure that the right rules are in place, the right information is in place so that it’s managed well and carefully.”

As the warming Arctic set another heat record in the first six months of the 2016 and the ice continued to decline to its lowest average level ever since satellite ice monitoring began in late 1970s, the issue of the Arctic fishery continues to preoccupy the fishing industry, environmental groups and Arctic nations.

Interim measures

Delegations from Canada, China, Denmark (representing the Faroe Islands and Greenland), the European Union, Iceland, Japan, South Korea, Norway, Russia and the United States met in Iqaluit, the capital of Canada’s Arctic territory of Nunavut from July 6 to 8 for the third round of talks on the future of the fishery in the central Arctic Ocean.

The meeting in Iqaluit followed previous talks that took place late last year and in April 2016 in Washington, D.C.

It also sought to build on a declaration signed last summer in Oslo, when Canada, Denmark/Greenland, Norway, Russia and the United States promised that their fishing vessels will stay out of a 2.84-million-square-kilometre (1.1 million-square-mile) zone in the central Arctic Ocean, an area bigger than the Mediterranean Sea, until there has been more scientific research done in the region to gauge fish stocks and the general health of the marine environment.

At the close-door Iqaluit meeting, all delegations reaffirmed their commitment to take interim measures to prevent unregulated commercial high seas fishing in the central Arctic Ocean, said the chairman’s statement.

Sustainable fishery

Unlike some other environmental groups that want to see a total ban on the Arctic fisheries, Laughren says his organization is very supportive of sustainable fishing.

“As a matter of fact, in our view, we really need fish in order to feed a growing and hungry world,” Laughren said. “It’s a great source of protein; exploiting fish involves low carbon emissions, low fresh water inputs; it’s a really healthy source that more than a billion people a day rely on.”

But when the commercial fishery moves up into the Arctic, a new area where enforcement is difficult, the science is poor, where irreparable damage can be done very quickly, the bar for a fishery management system has to be set very high before any fishing occurs, Laughren said.

‘Wild West situation’

(Oceans North-Pew Charitable Trusts)

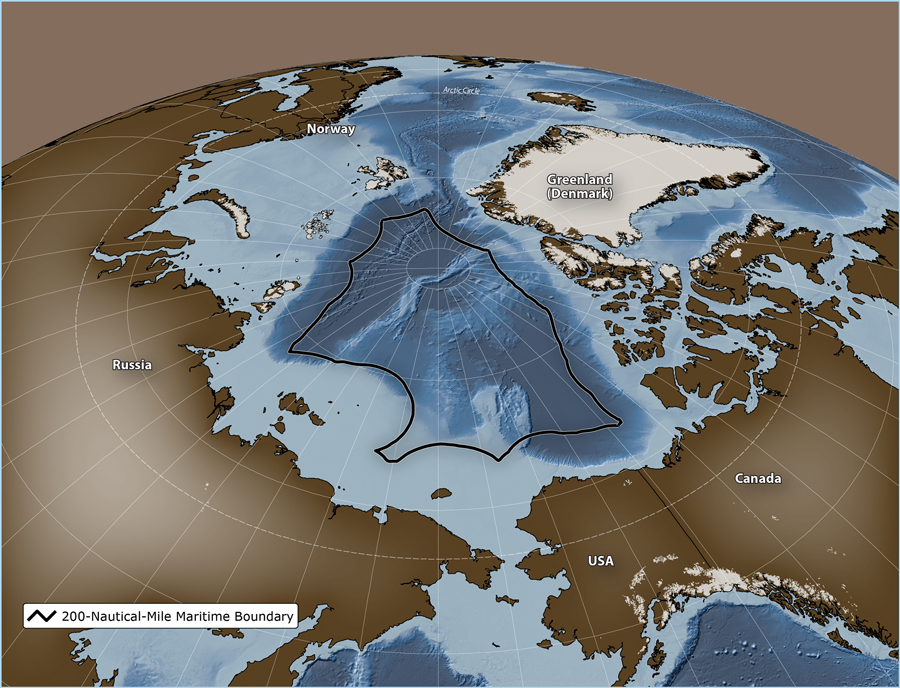

Under international law, fishing in the coastal areas off the Arctic Ocean – up to 200 nautical miles – off the coasts of Arctic states has to follow the rules and regulations of these respective nations.

“As soon as you go outside that, into what we call ‘the high seas,’ then you’re into a Wild West situation,” Laughren said. “And you have to make sure that there is some kind of an agreement where people follow the same rules, or else you really get a race to the bottom and people just fish it out.”

‘A mixed bag’

That’s why nations have set up regional fisheries management organizations, known under the acronym RFMO, he said.

“They have these in many places around the world, including off the Grand Banks of Canada, for example, and their history is a mixed bag,” Laughren said. “Like in a lot of fishing, there is a strong history of overfishing in these fish management organizations.”

But there are also a lot of lessons learned, he said.

“Everyone knows what a good fisheries management organization looks like and not surprisingly it’s the kind of things that you need to manage fisheries within a country,” Laughren said. “There is got to be transparency around both the information and the decision-making, there is got to be good science and then you have to follow the science.”

The fishing industry also has to take into account the ecosystem in which they’re operating, he said.

“You can’t just take the last fish possible, you have to leave some fish in the water for other species,” Laughren said. “You’ve got to have good enforcement and monitoring in place. And you’ve got to protect habitat, protect things that actually create the productivity of the fishery.”

Proper monitoring

One of the ways to ensure proper monitoring and enforcement is to have observers on board fishing trawlers “to make sure they are fishing where they are supposed to be fishing and catching what they are supposed to be catching and no more,” he said.

The various signatories to the future Arctic fisheries agreement can also set up catch documentation schemes to track the fish from the ocean to the market, Laughren said.

Oceana has also been working on developing another tool, Global Fishing Watch, a vessel monitoring system that tracks the location of ships of certain size through transponders connected to orbital satellites, he said.

Laughren said he would prefer to see a binding agreement, as suggested by the United States and others, instead of a non-binding agreement that will following Arctic fishery rules voluntary.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Is a fishing boom in the Arctic a sure thing?, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: EU drops seal-protection complaint against Finland, Yle News

Greenland: The donut hole at the centre of the Arctic Ocean, Blog by Mia Bennett

Norway: Climate change will lead to ecosystem clash, Barents Observer

Sweden: Record numbers for Swedish wild salmon, Radio Sweden

Russia: Oryong 501 sinking highlights Arctic fishing, shipping issues, Blog by Mia Bennett

United States: Ice retreat threatening Bering Sea pollock, Alaska Public Radio Network