German scientists sound alarm on Arctic trash

The amount of trash littering the bottom of the Arctic Ocean continues to dramatically increase despite the region’s relative remoteness from major urban centres, according to new research published by German marine scientists.

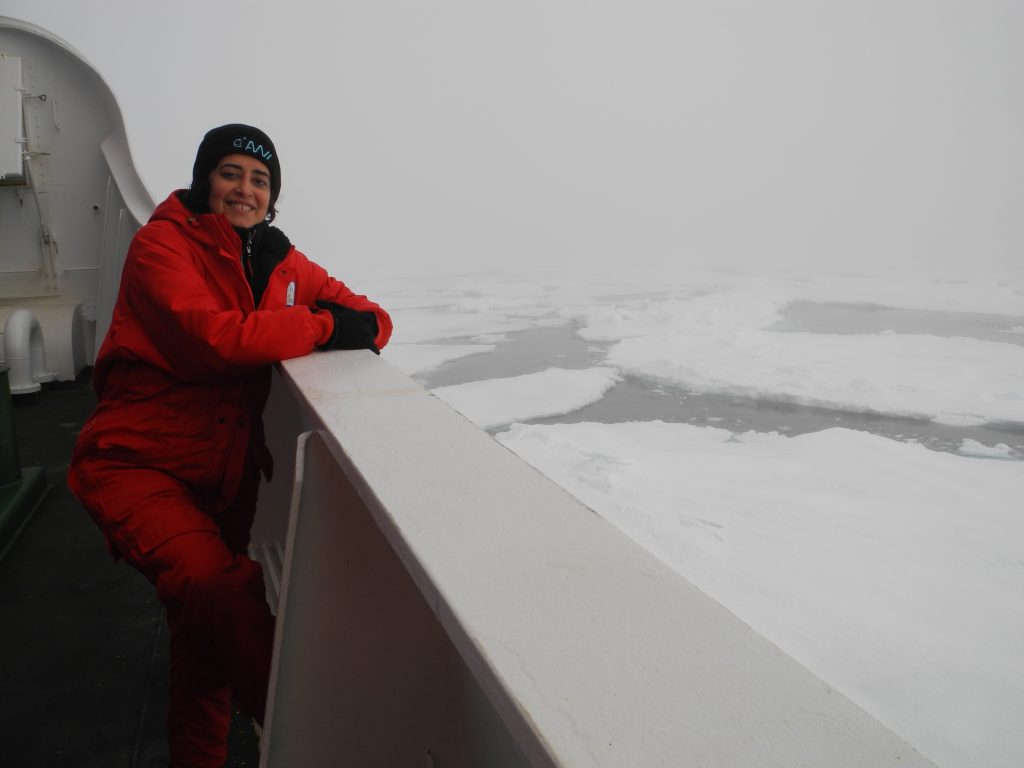

These pieces of plastic, fishing nets, broken glass found on bottom of the Arctic Ocean, thousands of kilometres away from the nearest metropolitan centres, pose a serious threat to the region’s fragile system, said Mine Tekman, a marine scientist with the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven, in northern Germany.

Since 2002, researchers at AWI have observed and documented the amount of litter at two stations off the western coast of Svalbard.

These stations are part of the AWI’s “Hausgarten,” a deep-sea observatory network, which comprises 21 stations in the Fram Strait, between Greenland and Svalbard.

The results of the long-term study have now been published in the scientific journal Deep-Sea Research Part I.

“We studied the amounts [of litter] between 2002 and 2014 and we found a high increase between those years,” Tekman, who is the lead author of the study, said in a phone interview with Eye on the Arctic. “Especially in the northern station more close to the ice – we call it the marginal ice zone – it’s 23 times higher if you compare 2014 to 2002.”

‘Butterfly effect’

That level of contamination is similar to one of the highest litter densities ever reported from the deep seafloor off the coast of Portugal and in the Mediterranean Sea, Tekman said.

“It’s like ‘butterfly effect,’ we throw some garbage from somewhere and it ends up in the Arctic,” Tekman said.

The researchers observed the ocean floor at a depth of 2,500 metres using a towed camera system, Tekman said.

“Each year we deploy some equipment, cameras wired to the ship, and then we take pictures along the same track,” Tekman said. “And then we analyse all those images for litter.”

Since the start of their measurements, the researchers have spotted 89 pieces of litter in a total of 7,058 photographs, according to AWI.

The scientists then rely on studies in the other areas of the world oceans to extrapolate the litter density to a larger area. Their calculations show that between 2002 and 2014 there was an average of 3,485 pieces of litter per square kilometre.

Pieces of plastic and glass are the most frequently observed pieces of litter observed by the researchers. While plastic can drift with ocean currents for thousands of kilometres, glass usually sinks almost straight down to the ocean floor, which points to local sources, such as increased shipping as the most likely source, Tekman said.

“Up until 2013, it was not prohibited to dump glass pieces into the sea,” Tekman said. “So most probably the glass items we saw were dumped before 2013.”

Ocean currents and human factor

Tekman said there are three possible sources for the litter on the bottom of the Arctic Ocean. The first one is the North Atlantic current, which, according to models, can transport trash dumped in Northern Europe all the way to the Arctic.

The second source is increased shipping in the area due to receding ice cover, she said.

“There are people on those ships and even though they don’t want to dump anything into the ocean, it’s almost impossible to avoid to accidentally losing litter items,” Tekman said.

The third possible source of increased litter pollution is sea ice itself, she said.

“If something gets trapped in the ice and then ice melts, this goes to the sea floor as well,” Tekman said.

Fragile ecosystem impact

The impact of this plastic pollution in the Arctic system is not very well understood, she said.

“In general, all these additives added to the plastic items they tend to leach in the sea water and so the animals get these chemicals into their tissues,” Tekman said.

Then there is the issue with microplastics, tiny pieces of plastic fragmented from larger pieces.

Furthermore, scientists don’t know how the larger pieces of plastics and litter affect other ocean organisms, Tekman said.

“When it comes to the Arctic and when it comes to the Arctic deep seas, since those ecosystems are really fragile, the increasing amount of litter simply to say is really threatening to these species,” Tekman said.

In addition, it appears that the litter could stay on the bottom of the ocean for an indefinite amount of time, she said.

The scientists were able to observe the piece of plastic on two separate expeditions in 2014 and 2015 virtually unchanged, Tekman said.

“We saw exactly the same piece of plastic attached or entangled with the exact same sponge and it looks exactly the same,” she said.

Tekman said she hoped their research will raise public awareness of the problem of plastic litter in the ocean without sounding too alarmist.

“There is this misunderstanding in the public that the sea floor and the seas are full of garbage everywhere,” Tekman said. “That’s not the thing, it’s not that horrible. But the horrible thing is we know that there are a lot of plastics floating in the ocean and they are getting fragmented into micrcoplastics.”

Missing plastic puzzle

Then there is the issue of the missing plastic in the ocean, she said.

Researchers still don’t understand where 99 per cent of the marine plastic litter ends up.

“One research suggest that there is between five and 13 million tons of plastic entering into the ocean and another researcher found out that the amount of floating plastic is 250,000 tons,” Tekman said. “There is a huge gap between these two numbers. This plastic should go somewhere.”

One theory is that most of that plastic ends up on the ocean floor, while some of it gets broken down into microplastics, she said.

“And we don’t know what this microplastic accumulation would cause in the future,” Tekman said.

The picture is further complicated by the presence in the water of microfibers released into the oceans from all the synthetic materials we use, she said. Research shows around 1,900 pieces of microfibers are released into the wastewater every time we wash our synthetic clothes, she said.

“There is no way to filter or clean the waste water from these fibres, so there is a huge amount of synthetic materials going into the oceans,” Tekman said. “It’s not visible and many people ignore it, but we should be thinking about that and we should maybe start changing our habits.”

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Arctic sea ice nears its minimum extent for 2016, Radio Canada International

Finland: Puzzling migration fluke brings thousands of Siberian birds to Finland, Yle News

Greenland: New model predicts flow of Greenland’s glaciers, Alaska Dispatch News

Norway: Record heat sends shockwave through Arctic, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Ancient virus found in Arctic permafrost, Alaska Dispatch News

Sweden: Sweden’s climate minister worried about Trump’s stance on global warming, Radio Sweden

United States: Alaska: Barrow’s record-warm October continues pattern associated with low sea ice, Alaska Dispatch News