A new digital atlas documents thousands of Yup’ik places in Alaska

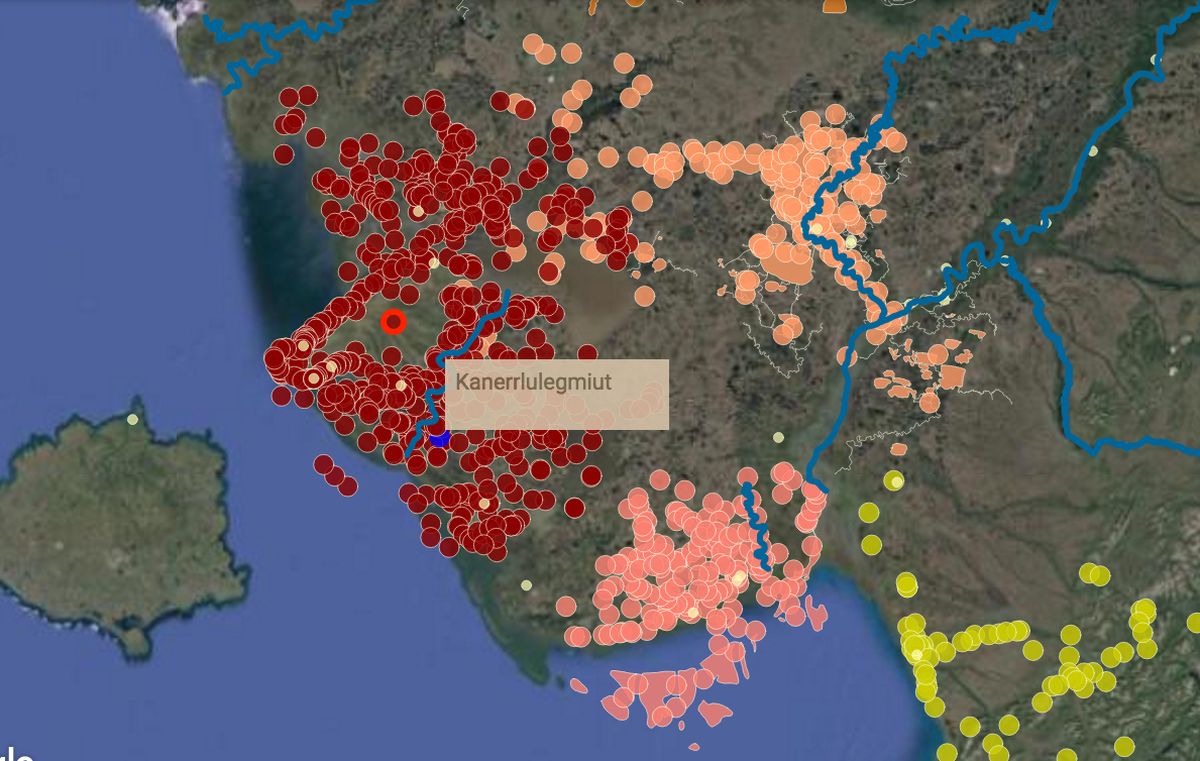

BETHEL – A project to preserve Yup’ik language and culture already has put more than 4,000 Southwest Alaska place names on a digital map: fish camps and ancient settlements, sloughs and ponds, even sandbars and underwater channels. Embedded sound files guide pronunciation to spots previously unknown in the bigger world.

Now the effort is moving to a new level. A three-day workshop in Bethel last week* drew teachers, a museum leader, curriculum specialists, technicians and those already involved in preserving the culture to explore how to add more features to the Yup’ik Environmental Knowledge Project.

Stories, photos old and new, and audio interviews could be inserted into the digital atlas, as well as additional features like descriptions of significant buildings, trails and travel routes. How the land is changing could be documented too. The workshop allowed a small group to practice adding to the digital map and to explore what resources are available.

The goal is to help Yup’ik people share their knowledge however they see fit, said Peter Pulsifer, a research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado in Boulder, who is helping to lead the project.

Collective effort

The work, which took off in 2012, is under the broader umbrella of the center’s Exchange for Local Observations and Knowledge in the Arctic. It is funded by the National Science Foundation to help collect, preserve and use the knowledge of locals.

For the work in Southwest Alaska, the exchange has an experienced partner, Calista Education and Culture, a nonprofit organization. The two groups put on the recent workshop.

Anthropologist Ann Fienup-Riordan, who is leading the Yup’ik Environmental Knowledge Project, is part of a trio who have created a number of Yup’ik books through Calista Education and Culture. She and others travel the region collecting traditional names and stories.

Already the online Yup’ik atlas is rich with thousands of colored dots marking sites. Two interns last summer recorded how to say them, Fienup-Riordan said.

“Elicarnarqaput kinguqliput makut atritnek,” a brochure says, quoting Ray Waska in Emmonak. “We must teach our young people their names.”

“Telling our own story”

Some stories from Fienup-Riordan’s recent work investigating the bow-and-arrow wars already are attached to the map.

“It’s not just a wilderness. It’s a populated place,” said Andrew Boyscout, a pastor from Chevak at the workshop. He has been working on a Chevak-area mapping and history project since 2000 that resulted in wall maps and books for classrooms. He came to the workshop to see how Chevak’s work fits into the regional project.

At the workshop, participants practiced inserting photographs and sound files into the digital marker for their communities.

Eva Malvich, who heads the museum at the Yupiit Piciryarait Culture Center in Bethel, noted places in Bethel where wild grasses can be gathered and used for basket making.

“This is our way of telling our own story, as Yup’ik people,” said Malvich, who is from Mekoryuk on Nunivak Island.

Boyscout said the work in Chevak was important in documenting where people used to go, old sod houses and ancient grave sites, as well as the fish camps still used. The maps already done have been provided to search and rescue groups, he said.

During the workshop, he marked where Chevak residents used to work together to hunt emperor geese before they became off-limits. After years of conservation, federal wildlife officials may open up hunts for them again.

Malvich asked whether any issues had arisen from disclosing the locations of hunting sites or old graves. No, said Boyscout. Chevak is open and wants to share information, he said.

Elders’ knowledge

Elders were asked at the start whether they wanted the public to have access to the digital map, Fienup-Riordan said. Across the board, they said yes. But some information might need to be protected, she said.

Three teachers at the workshop flew down from the Yupiit School District, one each from the Kuskokwim River villages of Akiak, Akiachak and Tuluksak, to learn about the technology and goals. One highlighted the Kuskokwim 300 sled dog race with pictures to show the significance of that event. Another connected the sound of a moose calling to a spot where moose appear.

If the school district decided to take on the project, students could interview elders, take pictures and upload images and audio files that, once vetted, could be connected to the map.

“We want to turn it over to the kids,” said Barron Sample, a teacher at the Akiachak school. “It’s their history, their identify. Most of us are from outside.”

Students could add material to the project and also use what is there to learn about their region.

“It’s full circle,” Pulsifer said.

Students could write their findings for the map in English and maybe in Yup’ik too. The work could be graded and incorporated into the curriculum, teachers said.

Gathering previous work

Jenine Heakin of Eek taught Yuuyaraq – Yup’ik curriculum – for more than 10 years. Now she is looking to help the Lower Kuskokwim School District use the digital map project. At the workshop, she experimented with showing travel routes on the map and also attached a photo of a handmade Native doll, an art that Eek is known for.

Fienup-Riordan suggested that the group consider three broad categories to layer over the names already on the map. One could cover subsistence and food gathering. Another could be on community and family histories. A third could be on elders and their stories.

One woman in Quinhagak already photographs wild greens from when they first pop up in the spring to harvest time, Malvich said. That could be a point on the map.

The museum was given boxes of old photographs rescued from a dumpster after The Tundra Drums closed its office in Bethel, Malvich said. The photos could be used for the mapping project, she said.

“It’s basically every village in the region,” she said.

She also has records from the early 1960s collected by a Federal Aviation Administration surveyor who saved everything, including old documents signed by long-gone elders.

“I always say the museum is a sleeping giant. It is what we do with it,” Malvich said.

Those archives, if digitized and organized through the online atlas, could be valuable for students doing historical research, Fienup-Riordan said.

The group next plans a teleconference in April to continue its work.

*This story was first published on March 3, 2017, on Alaska Dispatch News.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Canadian teacher wins $1M for her work with Arctic Inuit community, Radio Canada International

Finland: Nordic Sámi Convention agreement reached after more than a decade, Yle News

Norway: Sami National Day celebrates 100 year anniversary, Radio Sweden

Sweden: Sami Blood: A coming-of-age tale set in Sweden’s dark past, Radio Sweden

United States: ‘I Am Inuit’ goes from Instagram to museum in Anchorage, Alaska, Alaska Public Radio Network