`Enough of this postcolonial sh#%’ – An interview with Greenlandic author Niviaq Korneliussen

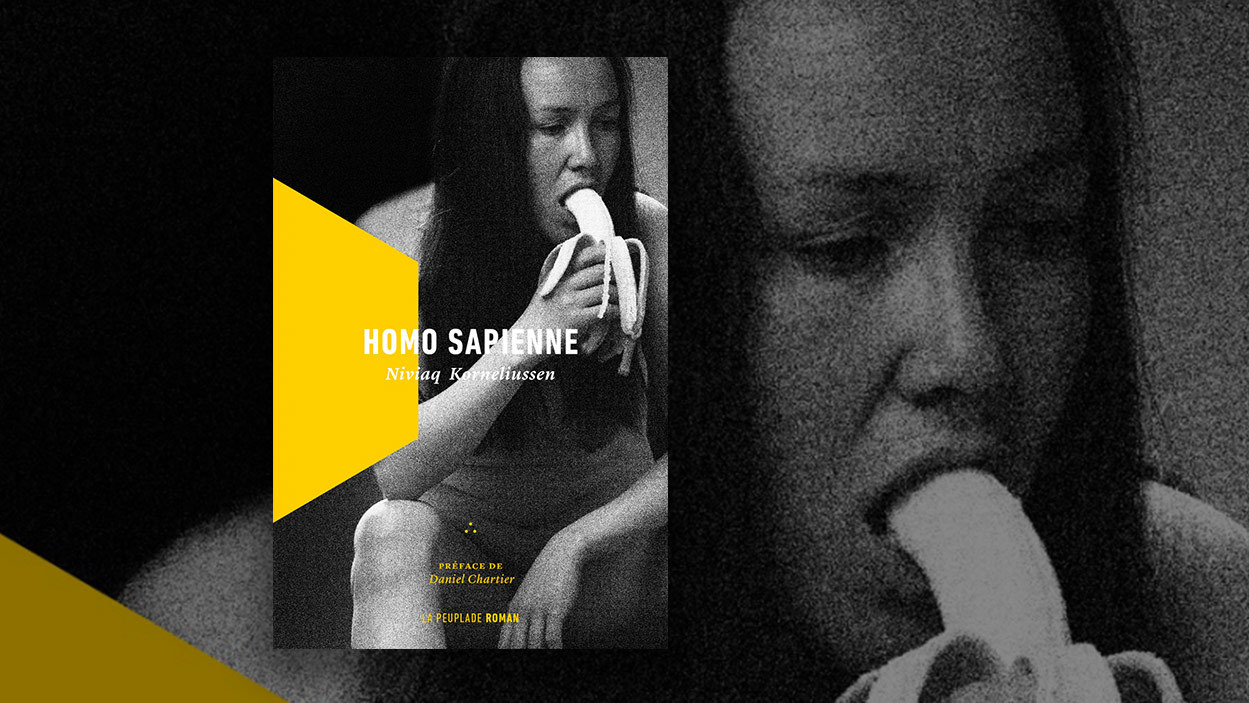

Greenland’s Niviaq Korneliussen is single-handedly redefining readers’ notions of northern literature with her first novel, Homo Sapienne.

In her book, five young characters make their way towards adulthood; navigating personal and social issues, relationships and sexual discovery.

Korneliussen puts traditional northern themes aside in her novel in favour of exploring an urban landscape where technology is omnipresent. From alcohol-infused parties, to moments of deep solitude, the young author dissects her characters’ intimate relationships and fears, excavating the universal human need to to connect.

Niviaq Korneliussen in her own words:

The buzz around Homo Sapienne has spurred international attention. It was translated for the French Canadian and German markets in 2017 and new translations are in the works in Icelandic, Swedish, Finnish, Norwegian, and even English. In Greenland alone, a country with 56,000 people, 3000 copies have been sold since 2014, an amazing feat for any artist, and even more so for a then 23-year old author.

To find out more, Eye on the Arctic’s Jean-François Villeneuve sat down with Niviaq Korneliussen to talk about her novel, Greenland and the importance of exploring themes like defiance and shame in her work.

Q: What’s the driving force behind your writing?

A: It’s my way of getting away. I grew up in Nanortalik a very small town in south Greenland, with 1500 people. As soon as I learned to write, it was my way of creating something that didn’t really exist in our society. It’s my way of communicating with other people, my way of expressing myself.

Q: You characters move easily between different languages. Throughout your novel, communication, or lack of communication, is a recurring theme. Is this a feature of modern Greenland?

A: When I started writing this book, it was very important for me to write a novel that people could relate to when it comes to communication and miscommunication. The five characters are communicating. They’re talking. They write to each other. They use text-messaging and Facebook. At the same time, they can’t really, really understand each other.

In Greenland, we use a lot of different languages. Greenlandic is number one, but you have to translate everything into Danish, because we’re a mixed population. But now, people are more and more interested in writing in English, because we’re trying to get away from the post-colonial period.

I find it very interesting because these characters are surrounded by people all the time. They’re partying, they’re text-messaging, they’re in love or hating someone else, but at the same time, they’re very lonely. They’re alone. I was very interested in this question of belonging, of being at home.

Q: Back home in Greenland, were people angry with the way you depicted your country? Were they telling you ‘You shouldn’t talk about these things,’ especially about gender identity and sexual orientation?

A: Well, not about the queer theme. Nobody ever told me you shouldn’t have done that. We’re actually very open, very sexually fluid and it’s getting better with gender roles. Our rights are exactly the same as straight people’s rights.

But there’s the chapter about Arnaq called the “Walk of Shame”. She’s an alcoholic who’s been abused by her father and she’s blaming everyone else for her problems.

In Greenland, some people think it’s very sad that I’ve written this book. They think I wrote it just to become popular in Denmark, because there’s a lot of stereotypes about Greenlanders there. Then, because I wrote about these things, the people in Denmark were like ‘So this is true, you’re alcoholic and you’re child molesters and everything else.’

Our society isn’t as simple as it seems.

People from the older generation also criticized my use of language. But, mostly, people find it very liberating because they think it’s necessary to talk about these things. We have a lot of social issues and problems in our country and I think a society has to be able to be criticized by its own people.

Greenland: already published

Denmark: already published

France/French Canada: already published

USA/English Canada: retitled Last Night in Nuuk, to be published in fall 2018

UK: retitled Crimson, to be published in May 2018

Germany: retitled Nuuk #OhneFilter, already published

Norway: to be published in fall 2018

Sweden: to be published in 2019

Source : milik publishing

Q: Despite being set in Greenland’s capital Nuuk, your story could have had taken place in Montreal, even New York…

A: That was very important for me to show. When I studied in Denmark, very intelligent people would ask me ‘How come you speak Danish? How come you know English? How can you do that when you’re, like, stupid? How can you study psychology when you’re a Greenlander? Do you have Internet? Do you live in very small houses in the middle of nowhere?’

It’s even worse in other countries, where they think Greenland is just an island with ice and we live in igloos and our pets are polar bears, stuff like that. Of course, we live in a very small society. It was important to me to show that we do live a modern life. We’re just a bit isolated.

Q: What’s your relationship with post-colonial Greenland and the legacy of Greenland’s colonial past in society today?

A: People in Greenland are trying to get back to their roots. It’s a very natural thing to do when you’ve been colonized.

It’s necessary for me as well, but at the same time, there’s a lot of hatred towards strangers and a lot of ignorance as well. That’s a huge problem, because we’re such a small society and we need everybody to be a part of it and to be able to cooperate somehow.

There’s also an independence movement in Greenland now and I find it very harsh. It’s dividing people into many different boxes. Who’s a Greenlander? Do you have to speak the language?

Niviaq Korneliussen on meeting Inuit students in Canada:

But the thing I’ve noticed when I’ve met with Inuit students in Montreal is that I felt like I was privileged somehow. They’ve been colonized very badly in comparison to us. They’re in danger. Their language is in danger. And their culture is very much in danger as well. I feel privileged that my colonizers weren’t that bad.

Q: You don’t really talk about parents in your book. Is that a kind of metaphor for Greenland?

A: Yes. And maybe you also noticed that nature isn’t part of this novel as well. That’s the very traditional way of storytelling, but everything has been said already. I don’t have to repeat everything that every Greenlander has said. I thought it was important to write something that’s very focused on these particular characters and their relationships to other people who are closest to them.

Niviaq Korneliussen on the traditional storytelling:

Q: Your story is made up of converging circles, like a spiral. Is this a metaphor for Greenlandic society?

A: Like yes I said in the book, “enough of that postcolonial piece of shit.” I have opinions about politics and the social issues we have in Greenland. I wanted to put in words how our society is most of the time. That you just go in circles and you can’t really go anywhere because you’re living on an island and it’s the same problems over and over again. For example, we were colonized by Denmark, and then in the 50s and 60s, the Danes moved everyone to bigger cities.

Greenlanders have criticized that so much. It’s the worst thing that could ever happen to Greenlanders, but now they’re doing the same. They’re moving everyone else from the small cities and villages to the big centres. A lot of villages are just closing and there’s no life in the small cities. In many ways, it’s a big circle that just goes around and around and you don’t really solve any problems, you just do the problem another way.

Q: Do you think Greenland, like your characters, needs to evolve to be able to go forward?

A: Oh yes, definitely. I don’t want to only criticize my people. There’s a lot of wonderful things going on. There’s a lot of young people who really want to make a change in our society. Fortunately, culture means a lot to us.

Q: You translated your book yourself from Greenlandic into Danish. Is there any symbolism in that?

A: I rewrote it in Danish. I really wanted everyone to be able to read my book, because there’s some Greenlanders who don’t speak Greenlandic, who only speak Danish.

The two languages are of course very, very different. It’s not similar at all.

It was pretty hard to rewrite, because I have a lot of poetry in the Greenlandic version. Some texts were completely changed in order to have the same power. But I think it was worth it, to make it more real. I don’t mind the fact that it was translated from Danish to French, because I still feel the Danish is mine.

Niviaq Korneliussen on rewriting her book in Danish:

Q : Was it important for you to use Danish to be able to share your work with a wider audience?

A: I feet that language is just a way to communicate. Of course, my Greenlandic, my mother tongue, is very important to me. I felt like I had a duty to show how Greenland was. And that was in Danish, because there’s a lot of people in Denmark who could learn a little bit from this book.

(The above interview has been edited and condensed.)

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Passing of celebrated Inuit carver Barnabus Arnasungaaq marks end of era, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Finlandia book prize shortlist: Climate change, fiction from the North and a political memoir, Yle News

Greenland: Canadian artist explores Greenland’s past, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Norwegian «slow TV» follows reindeer herd to the coast of the Barents Sea, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Karelian art on show in Russia, Yle News

Sweden: Sami Blood: A coming-of-age tale set in Sweden’s dark past, Radio Sweden

United States: National recognition for 2 Alaska artists, Alaska Public Media