Indigenous man in Northern Canada waiting for territorial government to waive name change fees

The Northwest Territories (N.W.T.) government is delaying waiving fees for Indigenous people that want to legally change their names back to their traditional names — after having told the CBC it would be changing the policy back in June.

Currently, the territorial government charges Indigenous people hundreds of dollars if they want to reclaim their traditional names, which may have been altered in the past through colonization and the residential school system.

It’s been more than three years since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission made a call to action for all levels of government to allow residential school survivors and their families to reclaim names changed by the residential school system, and to waive fees for five years.

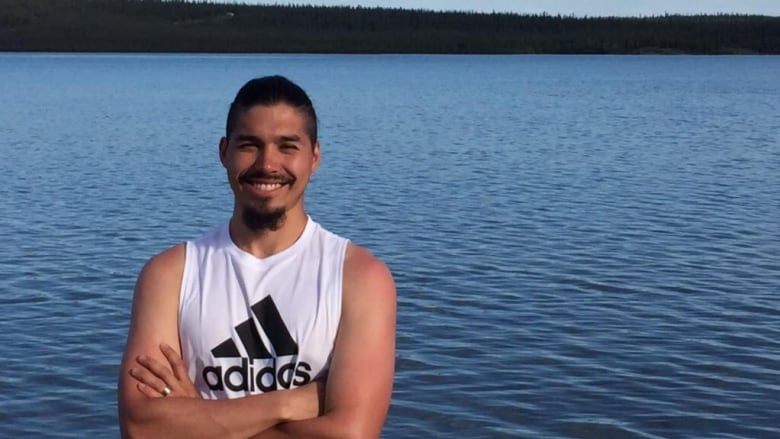

“I don’t know why they’re dragging this on,” said Denenize Basil of Lutsel K’e, central N.W.T., who legally changed his first name from Jacob years ago. He says Denenize means both “among the Dene,” and “how Dene lived in the old days” in Chipewyan.

CBC interviewed Basil about his name change in June. At the time, he said he also wanted to reclaim his last name, Dzën, after his late grandfather’s Chipewyan name meaning muskrat. But upon learning about the government’s imminent policy change he said he’d wait until it’s free.

“I’ve kind of been waiting for the government to make their choice, so I don’t have that financial barrier in the way,” he said.

The N.W.T.’s Health Department told CBC the policy change would be announced the week of National Indigenous Peoples Day (June 21). In August, it said the announcement would be in mid-September. Monday, a spokesperson said the change will happen “in the near future.”

“It’s kind of disappointing that it’s taking this long to have what’s ours. Hopefully it happens soon enough,” said the 24-year-old Basil.

“We can’t wait forever.”

Currently costs more than $300

As of this summer, the only province or territory to have acted on the TRC’s call to action is Ontario (southern Canada), which introduced its policy in January 2017. Since then, less than 10 people in the province have had their fees waived to reclaim their Indigenous name, according to Harry Malhi, a spokesperson with Ontario’s Health Department.

Ontario’s model allows anyone to reclaim an Indigenous name free of charge if the individual is a:

- Residential school survivor, seeking to reclaim a name changed through the system

- Spouse of a residential school survivor

- Direct descendant of a residential school survivor, or a spouse of a direct descendant

- Indigenous person seeking to change their name to a single name

Ontario is waiving fees until Jan. 11, 2022.

In the N.W.T., an average adult can pay more than $300 for a name change on major supporting I.D.s and documents.

Currently, it costs $134 for a territorial resident to legally change their name. It’s an additional $31 to change the name on a driver’s licence, $33 to amend a birth certificate, and $33 to amend a marriage certificate, according to the government website.

There are no fees to change a name on a territorial health card.

To change a name on a passport, the federal government requires the full renewal fee of $120 for a 5-year passport, or $160 for a 10-year passport.

Umesh Sutendra, spokesperson for the territory’s Health Department, said Monday that it takes time for legislation to go through administrative processes and that the territory is working on the process to waive fees for residential school survivors and their families.

“It’ll mean so much to our people,” said Basil, adding he’s happy about the positive change, acknowledging that the territorial government is starting to recognize Indigenous language and culture.

Taking back Indigenous names a ‘birthright’

Basil said it’s Indigenous people’s right to take back their traditional names.

“Our ancestors, they were born like that — so why can’t we be born with those names?” he said. “That’s our right. It’s our birthright.”

Basil said neither he, nor his mother attended residential school, but his grandmother did. He noted the five-year limit may be a short time frame and “a bit unfair,” especially for the next generation who may want to change their names.

Basil said he hopes with less barriers, more Indigenous people will start to reclaim their names.

“I think that’ll empower us and strengthen us,” he said. “The Chipewyan names are a part of us … In ways, it helped me find myself.”

Once the name change fee is waived, Basil is hoping his family members will follow after him.

“Sometimes I daydream, maybe if I’m the first one to change it, maybe my other family members will come back and change it too.”

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: New, Inuit-specific child care initiative will ‘right a wrong,’ says leader of Canada’s Inuit, CBC News

Finland: Sámi school preserves reindeer herders’ heritage with help of internet, Cryopolitics Blog

Sweden: Report sheds light on Swedish minority’s historic mistreatment, Radio Sweden

United States: Alaskan Inuit dialect added to Facebook’s Translate app, CBC News