Theoretical physicist helping scientists understand how glaciers flow

While glaciers have been retreating or melting since the early 20th century, little is understood about how exactly large ice masses flow when in contact with bedrock.

A new theoretical model of ice friction, recently published in The Journal of Chemical Physics, is aiming to address that knowledge gap.

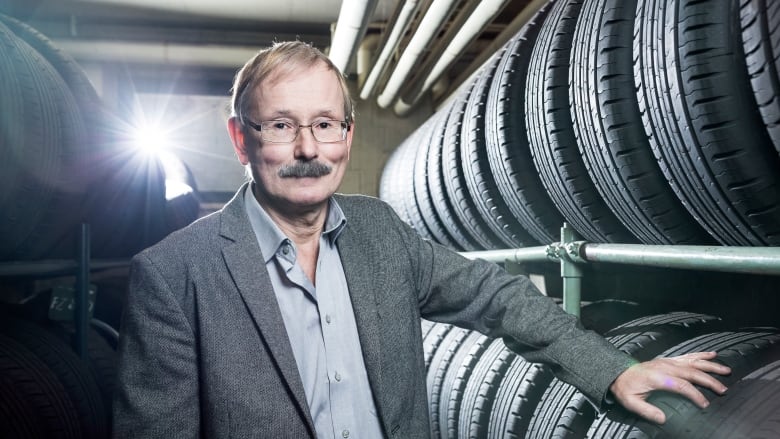

The model was developed by theoretical physicist Bo Persson with the Jülich Research Centre in Germany. He usually studies rubber friction and adhesion, and looked at previous studies of rubber surfaces and the leakage of rubber seals to develop the ice friction model.

“I could take knowledge I have gained during maybe 10 or 15 years of studies of other friction and quickly apply it to the glacier friction problem,” he said.

Persson explained that fast glacier flow is largely due to basal motion, or movement between the ice and the bedrock, along with complex sliding processes usually in the presence of water.

The most significant contribution his model makes, Persson said, is that it accurately describes the formation of cavities between the ice and the bedrock and how water can fill these cavities and become pressurized.

He said there is also flow within the ice mass itself. In areas where pressure is high, he said, ice can melt, while water can freeze in other regions where pressure is low.

“It flows almost like a viscous liquid, like honey.”

Projecting sea-level rise

Gwenn Flowers, a glaciologist and a professor of earth sciences at Simon Fraser University, said it’s well-known that water filled cavities play an important role in reducing friction at the bed allowing glaciers to flow fast.

Studying the basal motion of glaciers can be difficult however she said, requiring remote methods and laborious techniques as the bedrock is covered by tens of thousands of metres of ice.

“Having theoretical developments and numerical or computer models to help us understand how bed friction works is really important.”

Understanding how glaciers flow, Flowers said, is valuable for making accurate sea-level rise projections.

“A really big and important component [to sea level rise] is the fast flow of ice off the continental ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica into the ocean,” she said. “It’s this basal friction in part that dictates how fast this ice is going to be exported from the continent into the ocean.”

Flowers noted that while many people may not see glaciers on a daily basis, there are a lot of communities whose water comes from glaciers. The Greenland and Antarctica ice sheets, she said, store the equivalent of about 70 metres of sea level.

“That’s a lot of potential sea level rise and very small changes at the better these ice sheets could make the difference between meters of sea level rise in the next couple of centuries.”

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Dramatic changes to Yukon glaciers a warning for the planet, researchers say, CBC News

Finland: Northern nations pledge to reduce black coal emissions during Arctic biodiversity talks in Finland, Yle News

Norway: Climate change is driving micro-algae blooms into High Arctic and may affect food chains, says study, Eye on the Arctic

Russia: Russian researchers applaud construction of Arctic station, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Glacier in central Sweden “collapsing” as climate warms, Radio Sweden

United States: When the ice melts, what will happen to Arctic tourism?, Cryopolitics Blog