Russia scores scientific point in quest for extended Arctic continental shelf

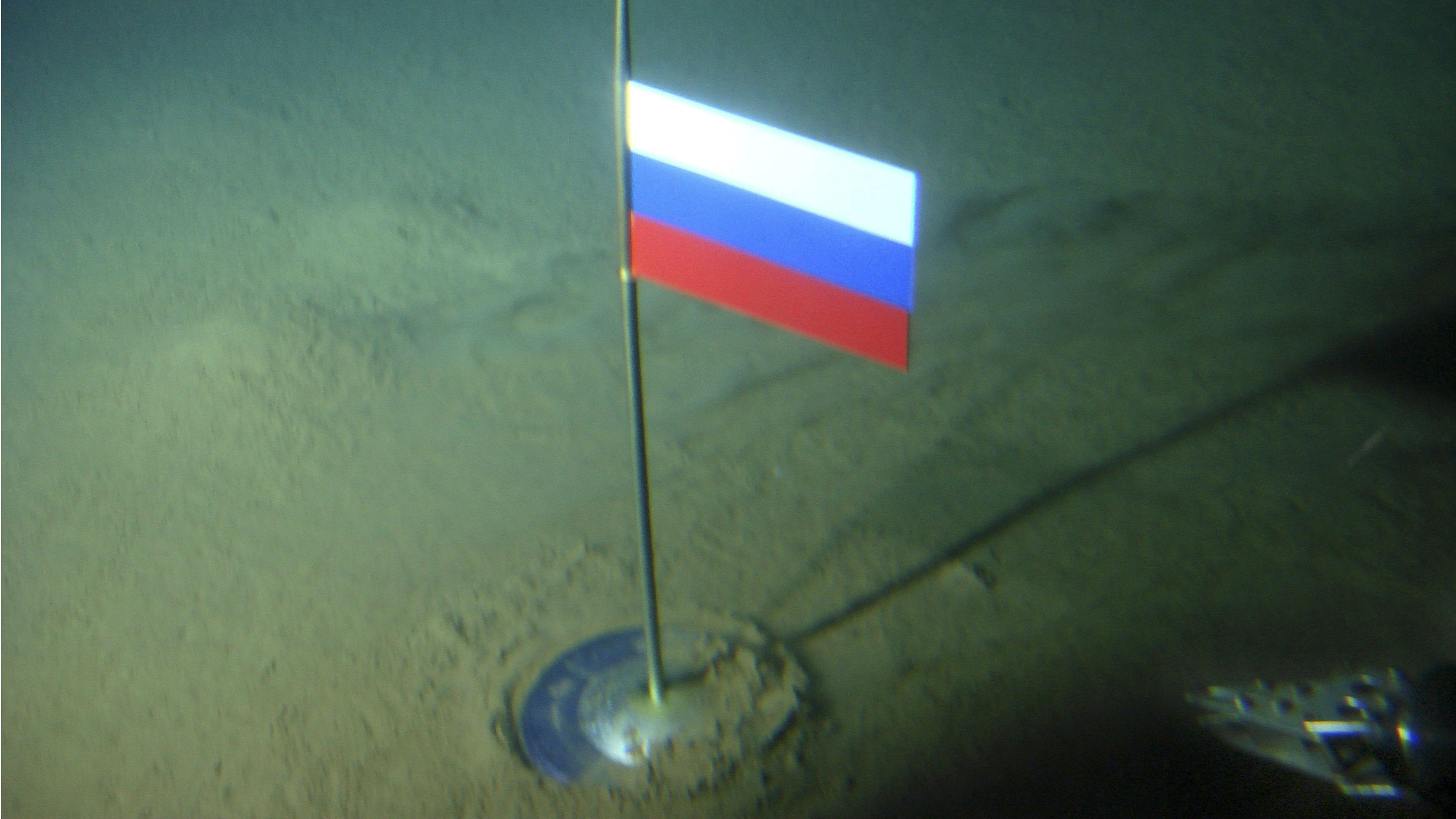

Russia has scored an important scientific point in its quest to declare vast swaths of the Arctic as part of its extended continental shelf in the rapidly melting northern ocean, according to Russian officials.

The United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf has declared that the outer limits of the Russian continental shelf submission are geologically similar to “the structure of the continuation of the shelf and the continent of the Russian Federation,” according to Yevgeny Kisselyov, head of the state agency in charge of natural resources exploitation, quoted by TASS news agency.

That’s one of the key scientific requirements for any country to able to claim an area of the world’s oceans as part of its extended continental shelf under the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

The Russian claim would include about 1.2 million square kilometres of the Arctic Ocean floor extending from the Russian Arctic coastline towards the North Pole.

However, experts warn that despite political spinning and media hype about the race for the Arctic riches, the scientific and diplomatic process of delineating the extended continental shelf in the Arctic Ocean will take years if not decades to settle.

A science-based process

Michael Byers, Canada Research Chair in Global Politics and International Law at the University of British Columbia, says it’s important to understand that the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf does not define borders.

It merely rules on the scientific validity of geological data presented to it in support of claims to extend the outer limits of a coastal state’s continental shelf, says Byers, who has written two books on international disputes and law in the Arctic – International Law and the Arctic and Who Owns the Arctic?

“It doesn’t give Russia that area of seabed or at least not all of it,” Byers says.

Russia was the first Arctic coastal state to submit its claim in 2001. In 2015, it submitted a revised claim after the UN commission found that its original claim lacked some data.

Denmark submitted its claims to the northeastern and northern continental shelf zones of Greenland in November 2013 and in December 2014 respectively.

Canada is expected to file its claim for the Arctic continental shelf this year.

Neither Russia nor Denmark with whom Canada’s claim will likely overlap have presented legal claims as to where the maritime boundary between the two countries should be drawn.

“This is a decades-long process and all the countries involved know that they will eventually be negotiating maritime boundaries in the Central Arctic Ocean to resolve the overlaps,” says Byers.

Extending outer limits of continental shelf

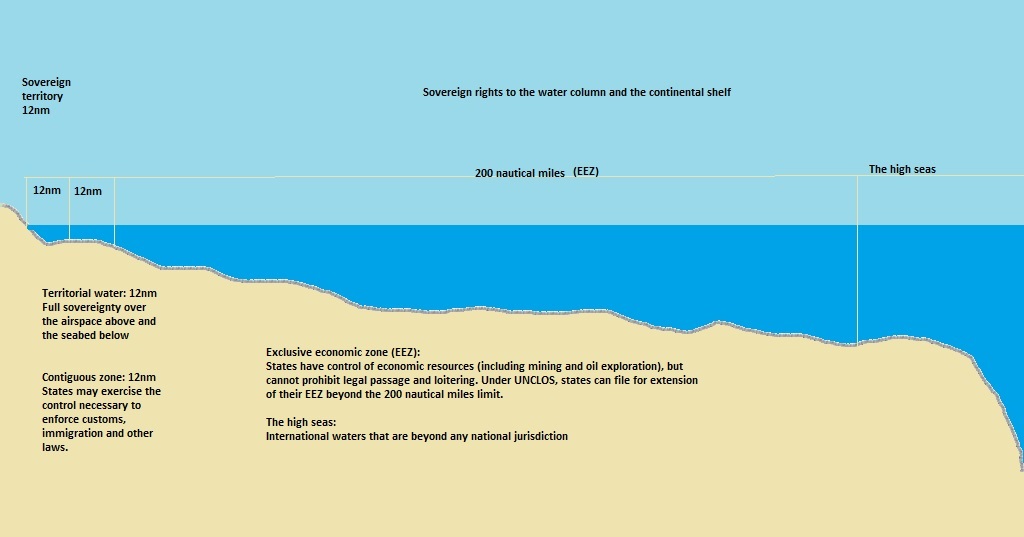

Under the UNCLOS, which Canada ratified in 2003, all coastal states have a continental shelf extending 200 nautical miles (370 km) from coastal baselines.

That 200 nautical mile area of the continental shelf forms the coastal state’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), where it has special rights regarding the exploration and use of marine resources on and under the seabed.

Coastal states can also extend the outer limits of their claim by 150 nautical miles (278 km) beyond 200 nautical miles if the shelf is a natural prolongation of their landmass.

However, in certain circumstances a coastal state can claim even further than 350 nautical miles.

For example, if a coastal state can prove that a submarine elevation is part of its continental landmass and if that elevation extends beyond 350 nautical miles from its coastal baselines, that coastal state could delineate an outer limit of its continental shelf past 350 nautical miles.

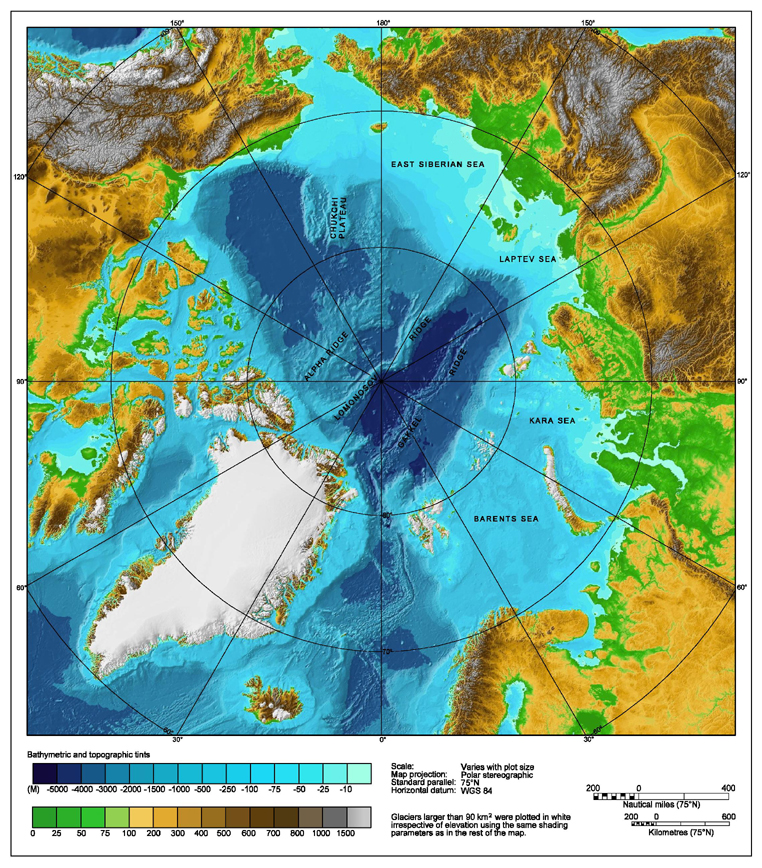

Canadian scientists claim that Lomonosov and Alpha-Mendeleyev Ridges, underwater mountain ranges stretching under the Arctic Ocean from Canada to Russia, are submarine elevations, thus giving them the right to claim the seabed under the North Pole.

Both Russia and Denmark are making the exact same argument.

In 2009, Norway became the first country to get its Arctic continental shelf submission in respect of areas in the Arctic Ocean, the Barents Sea and the Norwegian Sea approved by the UN commission.

In 2013, Canada submitted a partial claim for the continental shelf in the Atlantic Ocean.

The United States has not yet ratified UNCLOS and cannot make a claim unless they do so.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Canada to file submission for its continental shelf limits in Arctic Ocean in 2019, Radio Canada International

Finland: Norway will not give away mountain peak, The Independent Barents Observer

Greenland: Canada and Denmark set up joint task force to resolve Arctic boundary issues, Radio Canada International

Norway: Norway and EU clash over rights to resource-rich waters around Svalbard, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Russia wants Arctic delimitation deal with Denmark, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Norway and Sweden in quarrel over cross-border reindeer grazing, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: U.S. to collect Arctic data for modern navigational charts, Alaska Dispatch News