Blog – Climate change education is not just about science

Tackling climate change requires radical transformations across society – from individual households to national governments, from the language we use to the behaviours we adopt. Perhaps most important of all however is how we prepare future generations for what is to come: Not just how to adapt to inevitable changes, but how to actively change the course we’re currently on. In order to do so, we need to fundamentally challenge what constitutes knowledge and to inspire positive action.

As a scholar of Arctic geopolitics, the climate is a topic that features heavily in my research – whether I like it or not. The region has become a symbol of the crisis, known to be heating up at more than twice the average global rate.

Starving polar bears and melting glaciers have become mainstream illustrations for media coverage of climate emergency. Despite this, there seems to be a discrepancy between general knowledge of these issues and actual understanding of what they mean for our collective practices.

Environmental belonging

In my own research, I have asked both how political decision-makers and how youth in Arctic countries relate to and identify with the region. In both cases, the environment came up time and time again. For some, an Arctic identity was described as closeness to nature, as environmental consciousness, or a particular responsibility in the face of destructive commercial interests. In all cases, how we relate to the environment influences how we engage with it.

However, even for many living in the three Arctic states I studied – Canada, Norway, and Iceland – the High North can often seem far away. Walking the streets of Oslo, thawing permafrost and diminishing sea-ice cover might not be what determines your daily choices. And if you live even further from the region, statistics and scientific reports can feel distant from everyday life – no matter how alarming the headline.

Embodied learning

Bringing these topics into the classroom, educating about climate change is something I and many academics do. But as Matthew Hoffman recently wrote, coolly explained from a lectern “they weren’t getting it”. At least some students didn’t seem to, until I one day exclaimed that “I am terrified”, sending my notes flying as I threw my arms out. I didn’t expect the spike in attention, as students’ body language responded to the shift from numbers to emotions, and from scientific to embodied knowledge.

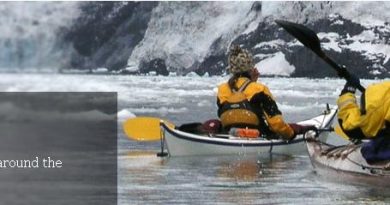

In the past, I have gone with students to North Norway, participated in a field-course in North-Western Russia, and a few months ago, I took part in the Students on Ice expedition to the Greenlandic and Canadian Arctic. On these trips, walking the tundra or trudging through snow, I have witnessed what can happen when you bring together my two past research subjects, political decision-makers and youth, outside the four walls of formal institutions: Whether student or staff, experiences can take you from factual knowledge to actual understanding.

This summer, around 130 students from 18 different countries took part in the aforementioned expedition run by Students on Ice: a foundation that brings students between 14 and 24 years of age on a two-week expedition to the Polar regions by ship. Of these, approximately 50% were Indigenous, and all eight circumpolar states were represented. I was there as an educator and social scientist, offering insights on Arctic geopolitics and governance – as were a number of other scientists, educators, Inuit Elders, artists, musicians, journalists, industry leaders and more.

However, this was a classroom unlike those I usually teach in – there were no whiteboards or desks in sight. Instead, we variably sat on the floor, around a gigantic circumpolar map; on the land after having gone onshore by zodiac; or balancing on ancient boulders as we moved through educational material. Students traced the Arctic Circle with the tip of their slippers; they smelled, tasted, and felt the changing flora; they drank glacial water; and they fished their own specimens for dissection (and dinner). But most importantly, they learned neither about nor on the land, but with it.

Reflecting on the last three weeks of #SOIArctic2019 (@StudentsOnIce) on my flight back to the UK, it will take a while to digest all the impressions and experiences, and to readjust to life post-expedition (!). But here are some of my thoughts (and photos) so far… [thread 👇] pic.twitter.com/sQWDqZF1H9

— Dr Ingrid A. Medby (@IngridAgnete) August 9, 2019

Indigenous knowledge

Prior to this particular trip, education staff were provided with three pieces of reading: An article by Peter Higgins on experiential learning, an article by Cash Richard Ahenakew on Indigenous education, and a commentary about climate disaster discourse. By moving teaching and learning outside of classrooms and lecture halls, these three topics converge in experiences that engage all the senses.

That is, not only should the educational experience happen through engagement with the land and ocean, but science also needs to be brought into conversation with Indigenous knowledge; not in a conversation whereby Indigenous knowledge is “included” in otherwise scientific projects, or whereby separate classes introduce students to the concept. As debates around decolonising curricula has highlighted across academic disciplines, diversity can all too often become a tokenistic inclusion rather than structural change. Instead, Arctic scientific expertise needs to be discussed alongside the expertise of Indigenous peoples, as equal and complementary knowledge systems. And indeed, from the outset of the Students on Ice expedition this summer, our movement through Inuit Nunaat (the Inuit homelands of Russia, Alaska, Canada and Greenland) was acknowledged and a topic running through all discussions.

Educating for change

While it may not fit traditional institutional “learning outcomes”, what education should strive to achieve is to instil hope and inspiration for action – even without the threat of a poor grade. Importantly however, you don’t need to travel to the Arctic itself to make this happen. As I have returned to research and teaching in the United Kingdom, the climate crisis necessitates everyone to take action – but to do so in a spirit of hope, and with a willingness to un-learn in the name of new and different knowledges.

Although there is much to be gained from overseas “fieldtrips”, there is also much to be learnt from engagement with our immediate surroundings – whether in the north or south. Images of polar bears serve as powerful reminders, but climate change is as relevant far beyond their habitats; as is the need to rethink how we teach and learn in the present moment.

In order to prepare future generations for what is to come, it is clear that we can no longer rely on just textbooks and slideshows. And more broadly, if we want to fully understand what climate breakdown means, we cannot rely on science to give us all the answers – or to prompt us into collective action. Instead, this is a time in which to radically question how we come to “know” the world around us.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Canada’s new Arctic policy doesn’t stick the landing, Blog by Heather Exner-Pirot

Finland: Climate change spurs growth of exotic fruit in Finland, Yle News

Greenland: Greenlanders stay chill as the world reacts to heatwave, CBC News

Norway: Arctic fox’s rapid journey from Svalbard to Northern Canada stuns researchers, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: A hot summer across the Arctic, Russian meteorological institute says, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Local councils more interested in climate change preparedness, Radio Sweden

United States: How should we measure Arctic identity?, Blog by Mathieu Landriault