New York Times article on Inuit draws backlash for reliance on stereotypes

When Francine Compton saw many Inuit frustrated by a recent article in the New York Times, she didn’t want to read it.

“I choose what I expose myself to, in terms of racism and stereotypes,” Compton said.

But as a director of the Native American Journalists Association (NAJA), she had to read the story, titled “Drawn from Poverty: Art was Supposed to Save Canada’s Inuit. It Hasn’t.”

The article, written by the Times’ Canada bureau chief Catherine Porter, drew criticism from Inuit and the wider public for playing into stereotypes of Indigenous people.

The story listed many stereotypes of Indigenous people, Compton said, including addressing poverty, suicide, plight, and addiction.

In a statement sent to Unreserved, The Times defended its story, saying the issues in the stories “came up repeatedly in the lives of the people we interviewed and profiled.”

NAJA stressed the need for an audit of how the article was published, said Compton, who is also an executive producer of national news at the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network.

The Times agreed to meet with NAJA to discuss the article.

How a game of bingo might help the Times

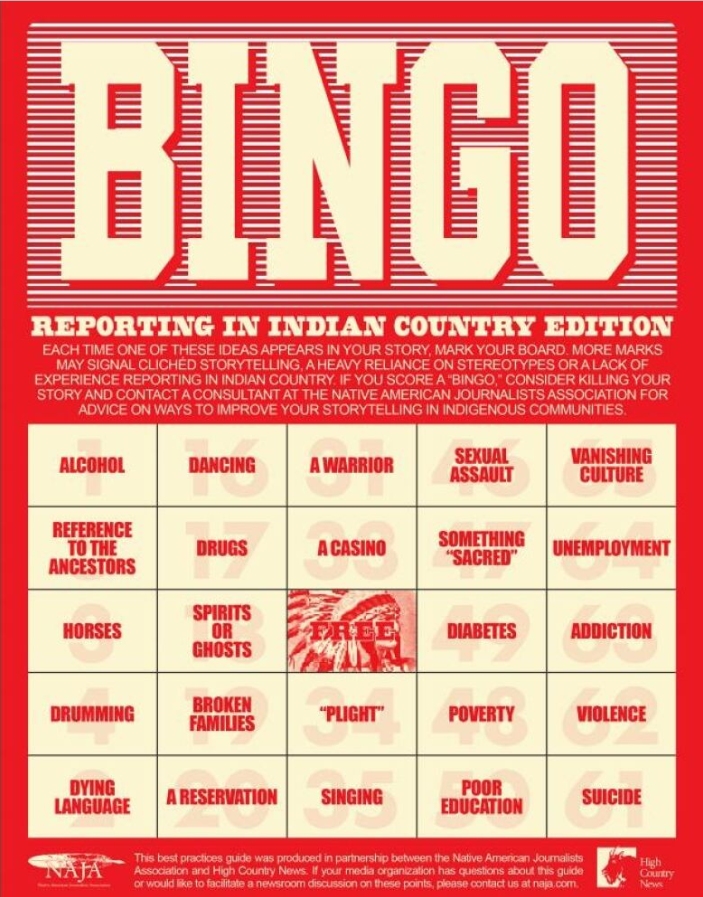

NAJA has created a unique bingo card to help journalists avoid reproducing recurring tropes of Indigenous people.

The bingo card is called “Bingo: Reporting in Indian Country Edition.” Each square represents a stereotype often used in the media, including poor education, unemployment, references to the ancestors, or a casino, among others.

The card suggests reading the story and marking stereotypes as they come up. The more squares you hit, the more likely the story has a heavy reliance on stereotypes, NAJA said. If you score a bingo, NAJA suggests killing the story and consulting with them on next steps.

Compton said she played a round of bingo using the Times’ article and found many stereotypes. It only took two paragraphs for her to score bingo. Compton said she even found some stereotypes that weren’t on the card.

“That [Times’ article] really bothered me as an Indigenous person in Canada because of their global audience and how the article portrayed Indigenous life in Canada as, well, poverty porn,” said Compton.

Compton said NAJA met with the New York Times on Nov. 11 to discuss the article.

“It was interesting to see the difference in perspectives,” she said. “[There were] just straight up differences in the way we read it and in the way they read it.”

This situation taught Compton a lot about where media is today on Indigenous reporting. She has one simple suggestion for newsrooms looking to improve their Indigenous coverage.

“Hire an Indigenous journalist,” Compton said.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Canadian Indigenous broadcaster launches French-language national news program, CBC News

Finland: BBC lists Sami journalist Sara Wesslin among world’s 100 most influential women, The Independent Barents Observer

Norway: Arctic-based news site Independent Barents Observer launches Chinese-language section, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Moscow-based media pretends to bring “objective” environmental journalism to Barents region, The Independent Barents Observer

Addressing the fact that there is poverty, abuse, alcoholism and other negative societal factors on reserve is hardly stereotyping. It is stating a fact and a very sad one at that. Instead of railing against a factual article in the NY Times, the author might devote more of her time to helping improve the deplorable conditions that do exist on many – especially rural – reserves because denying them hasn’t done a whit of good.

Ms. Ridley beat me to it. It is, among other things, our collective ignorance of too many of the “negative societal factors” in Aboriginal communities that has led to our moral and legislative ignoring of the needs of these often-marginalized Canadians.

I’m not suggesting that there are no media presentations of Aboriginal life that stereotype their subjects — indeed, there are far too many. The worst are those that romanticize a “lifestyle” without acknowledging the daily abuses all too common in these communities.