Blog – Summer 2020: When the unprecedented becomes the precedent

It’s raining. I’m delighted. A strange response from a Scot who has fled the damp British climate. I write this in a rural region of Germany, close to the river Rhine, famed for its fruit and veg and wine.

The famous river is at its lowest since September, although we’ve just come out of spring. The ground is already as dry as it might be at the end of a hot summer. The local papers are full of gardening tips for species of trees and plants that would be better suited to a more southern climate. Walking through our local forests, there are large swathes of dry, dead conifers. The bark beetles have had a feast on trees weakened by two summers of drought.

The rainwater butts out the back are long empty. My garden is crying out for water. And this is only the start of the fruit and veg growing season.

Unprecedented, unpredictable

It’s not only the coronavirus that has brought us a strange, new normal. Climate change has brought the reality of drought to places where this seemed unthinkable. We have seen record hours of sunshine, bright blue skies – and it feels like a deceptive kind of idyll. Corona is lurking in the background. The deadly virus that has brought the lifestyle we take for granted into question. Looming even larger is the steadily creeping heat that is changing our planet. Corona, climate change – in both cases, as we move into the second half of 2020, the “unpredictable” is now the “normal”. Expect the unexpected. Unprecedented seems to be becoming the precedent. We are entering unknown territory. It’s weird. It’s scary. Like a science fiction scenario Ray Bradbury might have come up with.

Siberia sizzling

Leaving the long-awaited rain to do its stuff, it’s time to retreat indoors and catch up on what’s happening in the Iceblogger’s beloved Arctic. The “icy north” is hotting up faster than ever. “Red alert for northern Siberia as heat shocks threaten life on tundra”, writes Atle Staalesen in the Barents Observer on May 25.

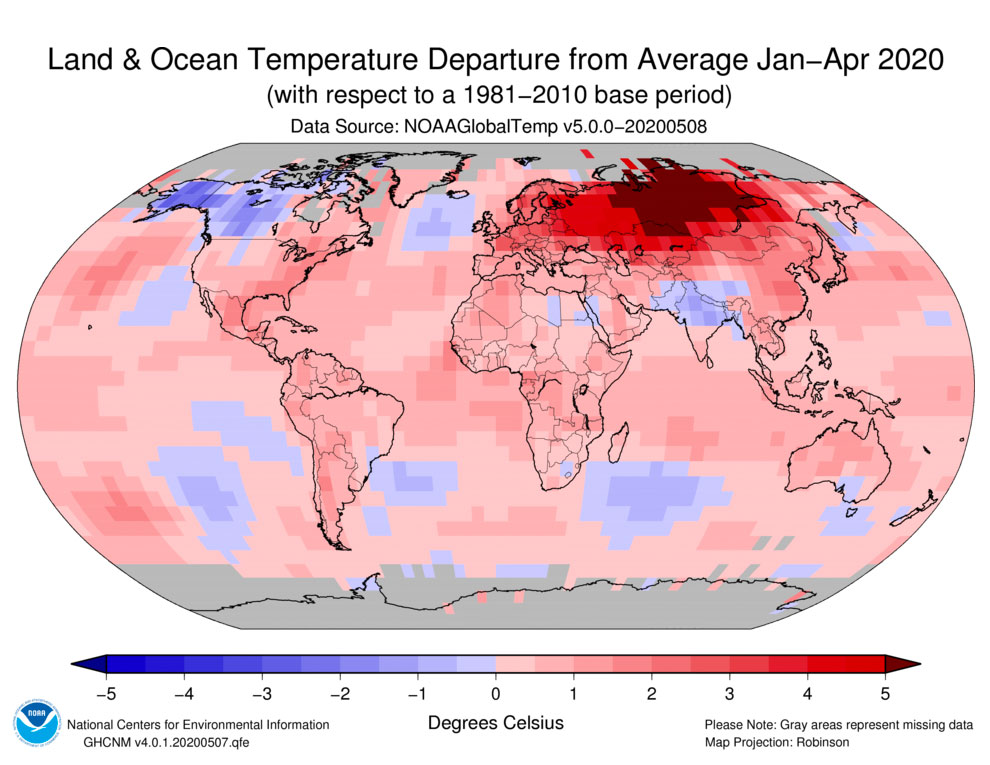

The U.S National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has published new temperature maps showing unprecedented warming across this vast region of the Russian Arctic. They show deviation from normal temperatures of more than five degrees Celsius over major parts of Siberia (relating to a base period of 1981-2010).

The area is among the regions of the world which are warming fastest. These record-beating temperatures have been prevailing for months. The trend has been going on for many years, Staalesen writes, pointing out that the same maps are made available by Russia’s Meteorological Service, Roshydromet. He quotes its latest climate report saying average winter temperatures along the Northern Sea Route, the waters along the country’s Arctic coast, have increased by a staggering five degrees since the 1990s. (Thanks to the Barents Observer for drawing attention to these maps and data on the Russian-language website).

Temperature maps from Roshydromet show another heat wave in mid-May, with parts of northern Siberia, including remote Arctic peninsulas showing an average temperature on the 23rd May as much as 16 degrees Celsius higher than normal.

According to Roshydromet, 2019 was the second warmest year in the Arctic since measurements started in 1936.

No relying on precedents

One result of the warm spring in Siberia has been that the ice on the region’s major rivers has broken up much earlier than usual. I came across an interesting eye-witness account by anthropologist Florian Stammer in Arctic Anthropology on May 19 :

This year this is happening earlier than usual all over the Russian Arctic, he goes on, from 10 days earlier to as much as a whole month earlier in some places :

“In Salekhard where I’m now the ice on the River Ob’ started moving already on 12 May, which is according to local news almost three weeks earlier than usual.”

Winter roads closed all year for cargo trucks

In Dudinka, the capital of Russia’s most northern Arctic region Taimyr, the ice on the Yenisey started moving on the 16 May. In 1936 it was an entire month later.”

He notes that the temperature in Novosibirsk, where the Ob starts, was already above 20°C at the end of April, and the locals report a mild winter.

“These Arctic Rivers are crucial in winter as ice-roads, and the thinner their ice is, and the earlier they break up, the less cargo you can bring on these ice-roads to all the settlements along. In the main reindeer herding headquarters of Yamal, Yar-Sale, the winter road was closed for cargo trucks officially all year. This was unheard of”, says Stammler.

He sums up the consequences for those who live in these northern regions :

“Such conditions mean that you have much higher prices for food in such places, and shortages of some stuff. For example petrol was not delivered by winter road to Yar Sale in 2020, so its price went up in the village so much that even some reindeer herders started bringing tons of petrol by snowmobile from the gas town of Nadym, almost 200 km south of Yar Sale (…) More importantly, for the herders in Yamal this also means they have to be crossing the Yuribei River in the middle of the Peninsula early enough over the ice, because once it melts, it will be too big for the herds to cross on water.

So, he concludes, a difference in the ice-melting times has big influences on Arctic mobility.

Siberia, Alaska smouldering underground

Scientists warn of zombie fires in the Arctic was the headline of a story on phys.org on May 27. I won ‘t comment here on why a story appears to be carried more widely or reach a wider audience if the fires are described as “zombie” rather than, say a “holdover” fire, or a fire which is still smouldering underground and could re-ignite on the surface.

Mark Parrington, a senior scientist and wildfire expert at the European Union’s Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Service, appears to have coined the term :

It is worrying to think that there are fires left over from 2019 which are still smouldering away underground and can re-ignite on the surface. Last summer, the northern hemisphere saw fires across wide areas of Siberia and Alaska which were unprecedented (that word again) in scale and duration.

“We may see a cumulative effect of last year’s fire season in the Arctic which will feed into the upcoming season, and could lead to large-scale and long-term fires across the same region once again,” Parrington said.

Europe has seen the kind of record temperatures and dryness already this year which increase the risk of wildfires.

Summer sea ice, a thing of the past ?

As far as the Arctic sea ice is concerned, the outlook is equally dim as we continue into the summer of what may well be the hottest year we have known. Since researchers began keeping satellite records in 1979, summer Arctic ice has lost 40 per cent of its area and up to 70 per cent of its volume.

Scientists have now worked out that the Arctic Ocean is likely to be ice-free at least some of the time every summer by as early as 2050.

The study, Arctic Sea Ice in CMIP6, published in Geophysical Research Letters analyzed recent results from 40 different climate models.

In an article published by Radio Canada International, Levon Sevunts notes that the ice still disappeared even in some simulations where CO2 emissions were rapidly reduced.

“The key point is that we have now reached a point that whether we are very aggressive in cutting our emissions or whether we go business as usual, we will be seeing years without any ice in the Arctic Ocean in the summer,” said study co-author Bruno Tremblay, associate professor in the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at McGill University, in an interview with Radio Canada International.

What we can influence is how often this will happen.

“If we do severe cuts to our CO2 emissions, it will be an occurrence that happens once in a while but it will still occur.”

The ice-free season is also expected to get substantially longer, he added.

Tremblay says the last time the Earth experienced conditions like these was about 6,000 years ago:

“And what we’re going to see at the end of the century, you’re going to have to go back even further back, like hundreds of thousands of years, millions of years back when you saw conditions that warm.”

Greenland: more melt to come

The Greenland ice sheet could also be heading for another record melt this year. In an article for E&E News published on Scientific American on June 3, Chelsea Harvey describes the southern part of ice sheet melting at its highest rate this season, with temperatures nearly 20 degrees Fahrenheit higher than usual in some areas.

The melt season started on May 13 – nearly two weeks earlier on average over the last few decades, Harvey writes.

She quotes Jason Box, ice expert with the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland who stresses the lack of snow as an important factor increasing the possibility of an above-average melt year. Snow has begun to disappear fast along the margins of the ice sheet, exposing bare rock and ice. When the snow, which normally helps reflect sunlight away from the earth, melts, more heat is able to get through, warming the surface and causing faster melting. The exposure of bare ice is happening earlier than usual this year, says Box.

“So, all else equal, we can expect more melt this year”.

A recent study published in The Cryosphere concluded that last summer’s extreme melting in Greenland was caused not only by warm temperatures, but by exceptional atmospheric circulation patterns. Because climate models that project the future melting of the Greenland ice sheet do not currently account for these atmospheric patterns, they may be underestimating future melting by about half, according to lead author Marco Tedesco from Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

Tedesco and co-author Xavier Fettweis, from the University of Liège, found that the record-setting ice loss was linked to high-pressure conditions that prevailed over Greenland for unusually long periods of time in 2019.

In a nutshell, they found that the high pressure conditions stopped clouds forming in southern Greenland. Clear skies let in more sunlight to melt the surface of the ice sheet. And fewer clouds also meant much less snow to add to the mass of the ice sheet. The lack of snowfall also left dark, bare ice exposed in some places, which absorbed more heat and exacerbated melting and runoff.

It seems this was not just a one-off event. The scientists say the conditions which led to the massive melt are probably connected to changes in the jet stream, which has become wavier – because of climate change.

So these “exceptional” atmospheric patterns could well become more common over Greenland.

Since current global climate models aren’t able to factor that in, Tedesco says they could well be underestimating the mass loss caused by climate change by as much as half.

Unprecedented – and human-made

“The human fingerprint on the climate is now unmistakable and will become increasingly evident over the coming decades”, the UK Met Office confirmed with a set of figures exclusively compiled for The Guardian to mark the 30th anniversary of its Hadley Centre for climate science and services.

Peter Stott, a professor and expert on climate attribution science at the centre told the Guardian global temperatures were now above any level in the Met Office measurements since 1850, or indirectly calculated through tree rings going back thousands of years. “Carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere are also higher than anything seen in million-year-old ice cores. We are seeing an unprecedented climate,” Stott said. “The human fingerprint is everywhere.”

The State of the Climate report published in March by the WMO and the UN comes to similar conclusions.

A recent decadal forecast by the UK’s Met Office indicates that a new annual global temperature record is likely in the next five years. Global temperature 2020-2024 is expected to be between 1.06°C and 1.62°C above 1850–1900, said WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas at the same event.

So where do we go from here?

At that launch event (in March, the provisional statement was issued in December 2019) Mr. Guterres said the year 2020 would be “pivotal for climate action if the world is to control ever worsening impacts and indicators of climate change before it is too late”.

Unfortunately, that key year is already half over. And apart from the brief respite somewhat tragically conferred on us by the corona pandemic, there are few indications that a long-term turnaround at the necessary speed is in the offing.

Alas. Patricia Espinosa heads up the UN Climate Secretariat, the UNFCCC, based in my current home-city, Bonn, Germany’s UN city. In a recent interview for our Bonn newspaper, the Generalanzeiger, she had to concede:

“With the current pledges submitted, we will not reach either of these goals.” (My translation from the German.) Climate change, she says, is moving faster than we are. That probably doesn’t surprise many of us.

The annual UN climate extravaganza should have been held in Glasgow, my old home town, this November. It has been postponed until the same time next year. So does that postponement represent a risk to climate progress or could it be a blessing in disguise?

Think how many emissions have been saved. Our governments – in theory – have time to reconsider priorities, against the background of the lockdown. The corona crisis, we are hearing from some source or other every day could be a chance to abandon the “old normal” and opt for a greener economy.

So will countries bring much more to the table when Scotland hosts that meeting one year on? Or will the need to recover from this crisis be just an excuse to carry on with business as usual – and maybe a little more to compensate?

In an interview with the Scots paper The Herald, Ms Espinosa said: “If done right, the recovery from the Covid-19 crisis can steer us to a more inclusive and sustainable climate path.”

In her interview with the Bonn Generalanzeiger, she expanded the connection:

The virus is not just an accident, she said, human influence was decisive.

That makes so much sense. A win-win situation for all? I for one have really been enjoying the clean air lockdown has brought us, free from fumes from air and road traffic. That must be so much more the case in the polluted megacities of China and India. We could keep that.

CO2 at an all-time high in the atmosphere

Alas, air pollution in China is already getting back to pre-lockdown levels. And the other major player, the USA, is heading back into full emissions mode.

Another sobering reality is that CO2 in the atmosphere is at an all-time high in spite of all the shutdowns. Surprise, surprise. More than two and a half centuries of increasing emissions can’t disappear overnight – not even if we stopped emitting now, completely.

Aaron Kiely is a climate campaigner at Friends of the Earth in the UK. Interviewed by The Herald about the postponement of the climate talks, he commented:

Unfortunately there are some key international leaders who aren’t prepared to do that – either to combat corona or climate change.

Germany pushing for alternative energies

But there are others. The government here in Germany has come up with a package to help the economy recover which includes, for instance, support for alternative energies. They resisted pressure from the auto giants to subsidise petrol and diesel cars. At local level, our council is improving the infrastructure for cyclists and symbolically closing one road between villages to all but bicycle traffic.

I’ll take those as signs of hope. The rain has stopped. I’ll go out and check up on my lockdown-inspired vegetable seedlings – and see if those rainwater butts are half-empty – or half-full.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Ice-free Arctic summers likely by 2050, even with climate action: study, Radio Canada International

Estonia: Politician calls for stronger EU engagement in Arctic, The Independent Barents Observer

Finland: Davos: Finnish PM stresses importance of Arctic Council for region’s stability amidst climate change, Yle News

Greenland: Climate change master’s degree being planned for Ilulissat, Greenland, Eye on the Arctic

Iceland: Iceland, Estonia talk Arctic at Tallinn meeting, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Norway’s Supreme Court to decide landmark climate case against Arctic oil in November, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Clean-up of major diesel spill in Russian Arctic won’t be completed until next winter, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: New report criticises Sweden’s climate policies, Radio Sweden

United States: Trump, Greenland & the black carbon debate: Arctic stories to watch for in 2020 with Cryopolitics’ Mia Bennett, Eye on the Arctic