November ranks 2nd hottest on record for the Arctic and globe

November 2020 ranked second hottest on record, overtaking November 2019 for the No. 2 spot, according to scientists at the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

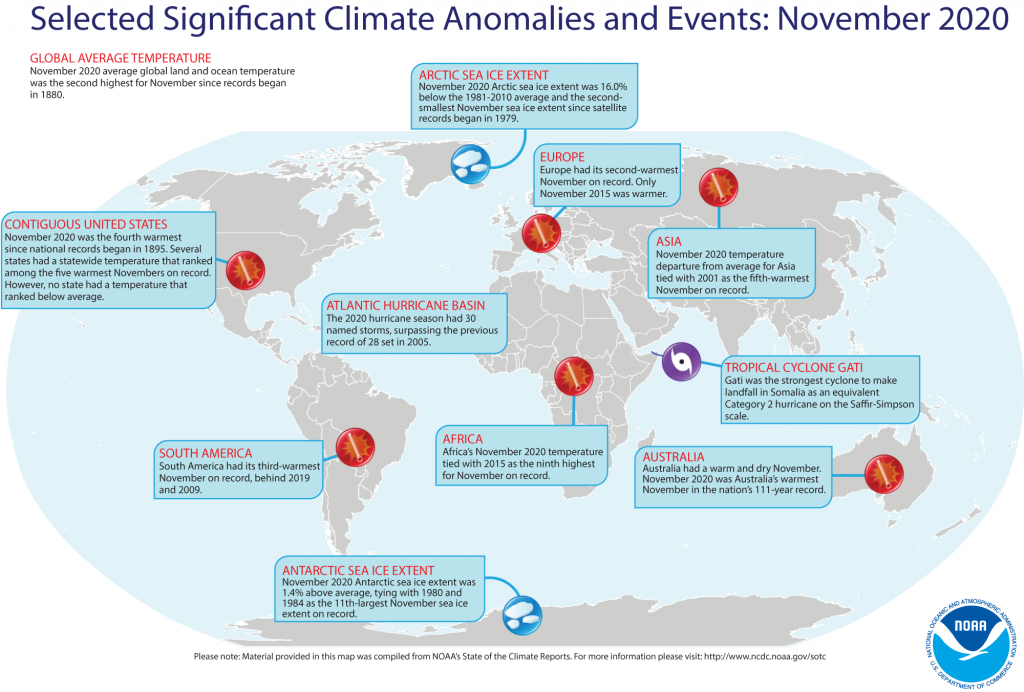

The average global land and ocean surface temperature for November 2020 was 0.97 C above the 20th-century average, according to scientists at NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information.

The Northern Hemisphere had its warmest November on record, with the Southern Hemisphere seeing its ninth warmest.

The most notable temperature departures were felt across parts of North America, northern Europe, northern Russia, Australia, central and southern South America, the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea.

Exceptional warmth also caused Arctic sea ice coverage to melt to its second-lowest November coverage on record, according to the scientists at the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) in Boulder, Colorado.

As was the case for October, air temperatures averaged for November were well above average over much of the Arctic Ocean, notably over open water areas.

“The month of November was again very warm in the Arctic,” said Walt Meier, a senior research scientist at the NSIDC.

“One of the things that we saw was a really slow freeze-up in the sea ice, it was record-low October into November.”

A ‘most extreme’ year

While scientists have witnessed this kind of slow freeze-up happening in recent years, this year it was the “most extreme,” Meier said.

Sea ice extent increased through November as part of the annual cycle of autumn and winter growth.

But the November average extent of 8.99 million square kilometers was 1.71 million square kilometers below the 1981 to 2010 average and just 330,000 square kilometers above the record low of November 2016, according to the NSIDC data.

“That’s because summers are so warm and the springs are so warm the ice goes away sooner – and the ice is more reflective of the sun’s energy than the ocean, much more so – so we have more ocean exposed for a longer period, which means the oceans are absorbing more of the sun’s energy and warming up more, and that heat prevents the ice from forming,” Meier said.

“So, even as we get into October and November, the sun has set and the atmosphere is cooling but you can’t grow ice because the ocean still has that heat.”

The delayed onset of freeze-up also amplifies the temperatures in the Arctic because this warm ocean layer keeps feeding heat into the atmosphere, Meier said.

“So we’ve seen near record-high or record-high temperatures in the Arctic in November,” he added.

Variation throughout the Arctic

However, the ice extent loss is not uniform across the Arctic, Meier said.

“Where we’ve seen the largest losses in terms of our long-term trends, it’s more on the Pacific side, north of Alaska, Canada, as well as on the Eastern Siberian side, like the East Siberian Sea, that has typically opened up very early,” Meier said.

“This year it was actually a little bit different – that side: the Chukchi Sea, the Beaufort Sea was more normal, at least into the spring and early summer. Where we saw the really early melt-back this year was in the Laptev Sea, which is further west than is normal.”

Scientists also saw the sea ice pull back a lot on the Atlantic side. In the Barents Sea ice-free conditions reached either record or near-record latitudes of up to 87 degrees north, Meier said.

In mid-August, German research icebreaker the Polarstern was able to cruise up to the North Pole with pretty minimal resistance, Meier said.

“What they experienced was kind of a broken-up ice floe with patches of open water that was a couple of metres thick, maybe half of its [normal] thickness and they could just cruise right through,” Meier said.

Ice-free Arctic summers in our lifetime

The thick multiyear ice is increasingly being replaced by seasonal ice that gets to about two metres thick at most, he said.

“You know, it’s not a matter of if we’re going to have sea ice-free conditions in the Arctic Ocean, it’s a matter of when, and it’s coming a lot sooner than we expected,” Meier said.

“We were looking at something that maybe was going to happen by the end of this century – so maybe that my grandchildren might live to see – but now it’s happening so fast and changes are coming so fast, that we’re looking at this in perhaps 20 years.”

Meier, 50, said he now expects to see these changes within his lifetime.

Scientists have a lot of unanswered questions about the downstream effects of these rapid changes in terms of their effect on mid-latitude weather patterns, he said.

“We still need better data on the interaction with the ocean both in terms of how much is the ocean causing the ice loss and then how much of the ice loss may affect the ocean and the ocean currents,” Meier said. “Those are big questions that may have big ramifications.”

That in turn raises further questions about how the Indigenous and northern communities that are already being affected by these changes are going to adapt to further changes and what needs to happen for them to adapt, Meier said.

There are also huge unanswered questions about how these changes will affect the Arctic’s ecosystems, its fauna and flora, he said.

“It’a a big interconnected system and I think as a grand question and one of the things that is still out there is how this interconnected system all fits together, and how it’s going to respond as a whole to the changes to the ice cover and the Arctic warming in general,” Meier said.

Related stories around the North:

Canada: 2020 shaping up to be among warmest years on record says WMO, Eye on the Arctic

Greenland: Rise in sea level from ice melt in Greenland and Antarctica match worst-case scenario: study, CBC News

Russia: Northern climate change will cost country €99 billion says Russia’s Minister of the Arctic, Eye on the Arctic

Sweden: Reducing emissions could create up to 3,000 new jobs in Arctic Sweden says mining group, Eye on the Arctic

United States: Indigenous wildfire knowledge to be key part of new Arctic Council project, Eye on the Arctic