“We still have a lot of healing to do with our fellow Canadians” – National Day for Truth and Reconciliation observed September 30

On September 30, Canada marks the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation for the first time. Something Inuit leaders say is an important step to educating the country on the experiences of Indigenous Canadians.

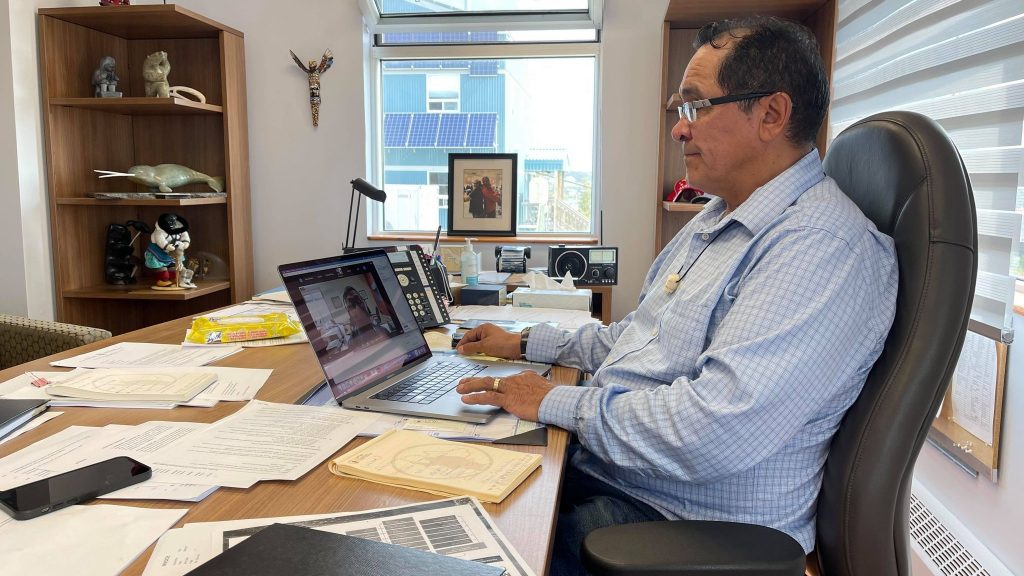

“This day that is given to Aboriginal people of this country is very much appreciated but it does not solve all our problems and the upheaval that Inuit had to go through because somebody else decided to come to our part of the world and take over our lives,” Pita Aatami, the president of Makivik Corporation, the Inuit land claims organization in Quebec, said in a phone interview.

“We still have a lot of healing to do with our fellow Canadians.”

The creation of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation was one of the recommendations in the Truth and Reconciliation Report.

Rebecca Kudloo, the president of Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada, says the holiday is an important step in honouring residential school survivors as well as an opportunity to advance the national reconciliation project.

“This journey of healing requires all Canadians to work together and recognize the history of injustice against Inuit, but also acknowledge the achievements and contributions of our people,” Kudloo said in emailed comment.

Kudloo says reconciliation is not just a political project but something for non-Indigenous Canadians to contribute to.

Participating in Inuit Day and National Indigenous Peoples Day, listening to Inuit elders’ histories and worldview, learning about Inuit culture and being open to learning from it, and creating safe environments for all Indigenous people, are all things non-Indigenous Canadians can do in their everyday lives, she says.

– Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action

Learning about about the status of Inuit women today, as well as Pauktuutit’s history, are also important, she says, because of unique pressures colonization has placed on women.

“Inuit women are some of the most vulnerable populations, who not only face the ramifications of colonization but also face other challenges like gender violence and inequality; therefore, the journey of reconciliation at times might feel harder for them,” Kudloo said.

Hard work still needed

Aatami said despite an increasing focus on reconciliation in Canada in recent years, still too few non-Indigenous people are aware that the residential school system is not just a legacy of the past, but something that continues to impact Indigenous communities and families today.

The National Day for Truth and Reconciliation can help contribute to that understanding, but it’s important that the symbolism of the day doesn’t replace that hard work still needed for Indigenous autonomy and self-determination, he said.

“We’ve come along way, but the mentality of a lot of non-Aboriginals in Canada is still that Aboriginals should cater to the non-native society, instead of [the non-Indigenous] trying to understand and respect Aboriginal people’s societies themselves. And without that, they’ll be no healing.

“My message when I speak to government is always the same, Inuit don’t want any more than their fellow Canadians, we just want equity.”

Honouring survivors

The history of residential schools in Canada dates back to the 1800s.

Inuit and First Nations children were sent to the federally funded, primarily church-run schools, far from their communities and their cultures, and often against the wishes of their families.

The goal was to assimilate the children into European culture. Physical and sexual abuse was rampant in many of the institutions, and many students were beaten for speaking their Indigenous languages.

Over 130 of the institutions were located across Canada and more than 150,000 Inuit, Métis and First Nations children are estimated to have been in the residential school system.

The last residential school in Canada was closed in 1998.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission was set up as part of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, a class action settlement set up to help former students. The commission ran from 2008 to 2015 and its final report included 94 calls to action. Call to Action 80 was the creation of a National Day for Truth and Reconciliation to honour survivors and reflect how the residential schools system impacted communities, families and Indigenous societies.

The bill to create the federal holiday received royal assent in June after the discovery of 215 unmarked graves in Kamloops, British Columbia (B.C.) in May on the site of a former residential school. This was followed by the discovery of hundreds of other unmarked graves across Canada, followed, including 751 in Saskatchewan, and 160 in B.C.’s Southern Gulf Islands.

The day is now an annual statutory holiday for federal employees and workers in federally regulated workplaces.

Some provinces and territories however are also giving their provincial or territorial public sector employees the day off, including the Northwest Territories and British Columbia. Provinces like Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia have made the day a provincial statutory holiday, while others like Ontario and Quebec have not.

Aatami said the decision is a lost opportunity for Quebec.

“It’s sad that the Government of Quebec doesn’t want to acknowledge the day for Aboriginal people and reconciliation,” he said, adding that he wrote to Quebec Premier François Legault last week to express his misgivings about the decision and urging him to reconsider, and is waiting for a response.

“Quebec should do the right thing,” Aatami said.

The National Day for Truth and Reconciliation also coincides with Orange Shirt Day, founded in 2013 to spotlight the legacy of residential schools. Orange shirt Day was initiated by Phyllis Webstad, a residential school survivor from the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation in British Columbia.

The day takes its name from when Webstad first arrived at residential school and had her new orange shirt taken away from her. September 30 was chosen because it was the day children were taken to residential schools.

Write to Eilís at eilis.quinn@cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: COVID-19 delays delivery of apology to Inuit residential school survivors in Atlantic Canada, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Sami Parliament in Finland agrees more time needed for Truth and Reconciliation Commission preparation, Eye on the Arctic

Greenland: Danish PM apologizes to Greenlanders taken to Denmark as children in 1950s, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Can cross-border cooperation help decolonize Sami-language education, Eye on the Arctic

Sweden: Sami in Sweden start work on structure of Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Eye on the Arctic

United States: Alaska reckons with missing data on murdered Indigenous women, Alaska Public Media