Arctic Security: Will Canada’s federal budget deliver for NORAD?

The North American Aerospace Defence Command (NORAD) has provided continental defence of North America for over sixty years, but urgently requires modernization.

Meanwhile Russia and China have spent more than 15 years investing massive resources in weapons technology and Arctic infrastructure, while Canada lags and its military is starved of resources.

With the Russian invasion of Ukraine putting unprecedented focus on Canada’s ability to defend the North, will the April 7 budget have what’s needed to turn things around?

CFB GOOSE BAY, Newfoundland and Labrador — It’s mid-March and 5 Wing Goose Bay in Atlantic Canada buzzes with activity. The North American Aerospace Defence Command (NORAD), the Canada-U.S. integrated military command responsible for the continent’s air defence and maritime warning, is in the midst of Operation Noble Defender.

Besides 5 Wing Goose Bay in Labrador, locations across North America were involved including Thule Air Base in Greenland; Canadian Forces Station Alert, Nunavut; Yellowknife, Northwest Territories and Whitehorse, in Yukon.

Noble Defender is a series of operations that takes place on average three to four times a year to demonstrate NORAD’s ability to respond to aircraft and cruise missile threats to North America.

March was chosen for 2022’s first iteration to exhibit to which point the command is able to operate in even the harshest Arctic conditions and in Goose Bay, they’ve been put to the test — over the weekend, winter storms have dumped up to 65 cm of snow in parts of Labrador but despite that, and the raging winds, 5 Wing has been able to keep the runways open.

“Our crews have been working very hard to keep our airfield open, operating and ready to receive our aircraft,” Lieutenant-Colonel Guy Parisien, the Wing Commander of 5 Wing Goose Bay, said.

“When you’re trying to confirm your ability to project your forces out, if you can do it during the most challenging conditions, then in ideal circumstances, you should be able to do it as well. That’s exactly why we’ve chosen this Noble Defender to take place at this time of year when we have typically challenging weather conditions, to prove our continued ability to project this.”

This year’s operation simulated threats approaching NORAD’s air defence identification zones across the continent, ranging from cruise missiles to American B-52 strategic bombers playing the role of threat aircraft.

Planning on this year’s operation started over eight months ago and is not in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But the war in Europe has taken discussions about NORAD’s long-neglected modernization off the back burner and pushed them back into the headlines.

On break from Noble Defender in March, Major-General Eric Kenny, Commander of the Canadian NORAD region, sought to reassure Canadians its military was ready and able to face threats it may be confronted with.

But he stressed that as other countries invest in new weapons technologies, NORAD needs to keep pace.

“I have extremely professional forces who are dedicated to the mission, who understand the security and defence needs of the Arctic and are ready to do the mission if called upon,” Kenny told Eye on the Arctic.

“Having said that, there’s a need to continuously look at where we have our infrastructure, what our capabilities are, and a modernization component that, without it, would have us fall behind our adversaries’ capabilities.”

But according to some defence experts, Canada has already fallen behind and questions remain about whether the political class has the will to do what’s needed to catch up.

“The Canadian military has been doing miracles on nothing, so it doesn’t incentivize a politician to say, ‘let’s give you more money,’” Andrea Charron, an Arctic security expert and director of the Centre for Defence and Security Studies at the University of Manitoba.

“But what the war in Ukraine has done is sharpening minds to realize that there are states that will use deadly force, that Russia is actually quite close to us in the Arctic, and if they can do unspeakable things in Ukraine, maybe what NORAD has been saying, that Russia is a proximate, persistent threat, maybe we should pay attention to that.”

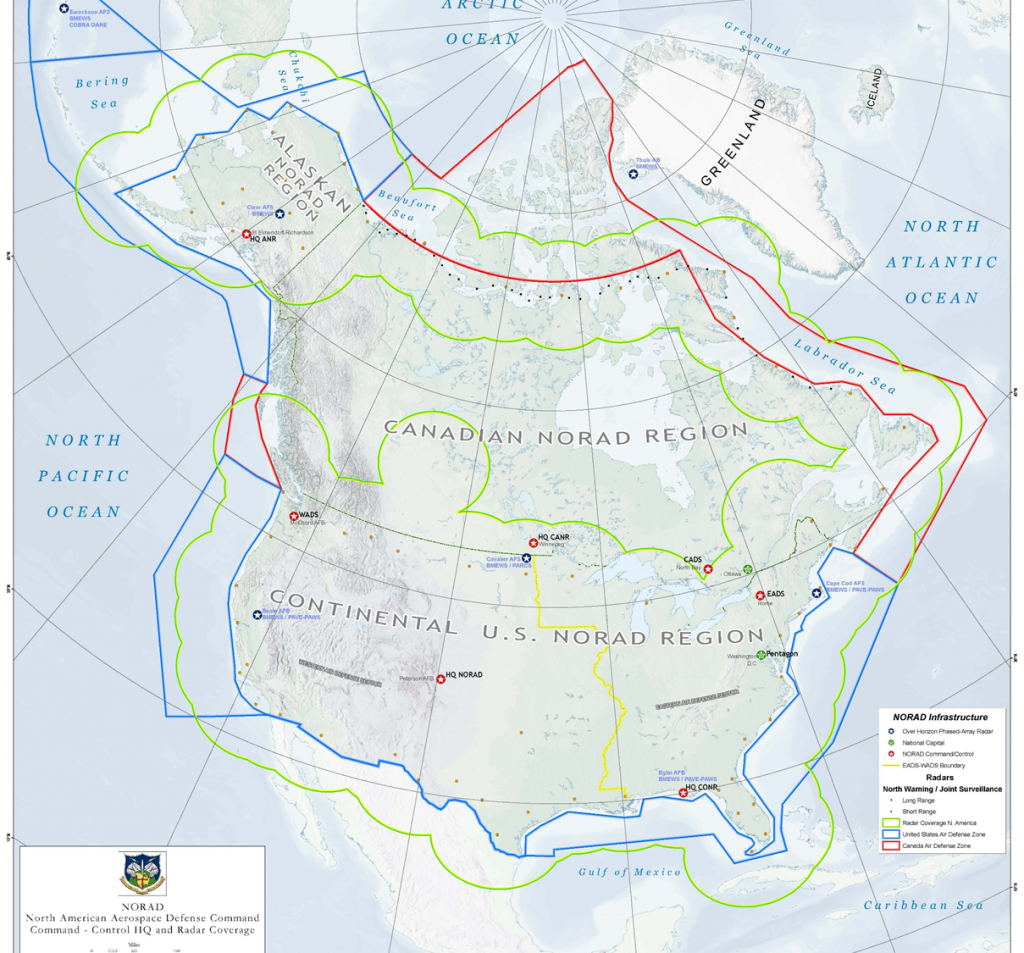

Set up in 1958 during the Cold War, NORAD’s mandate was to provide aerospace warning and control against Soviet aerial threats to North America. Maritime warning was added to its mandate in 2006.

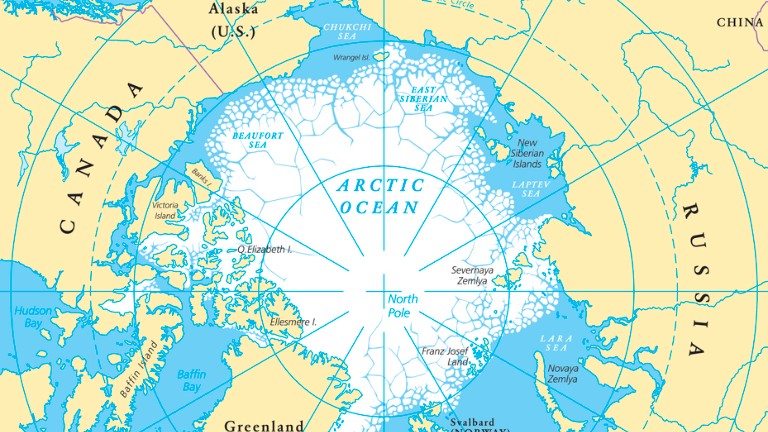

Currently, a chain of unmanned long and short-range radar station sites called the North Warning System stretches across the Arctic.

The sites are controlled and monitored remotely by NORAD from 22 Wing at Canadian Forces Base North Bay where the Canadian Air Defence Sector keeps track of everything entering Canadian air space.

However, experts have long sounded the alarm over the inability of the system, built between 1986 and 1992, to keep up with new weapons technologies.

“Canada has been part of deterrence system going back to the Cold War that involved the North American defence apparatus like NORAD, then we had NATO, and then our involvement in peacekeeping, all which were part of presenting a deterrent posture,” Sean Maloney, a military historian and nuclear weapons expert at the Royal Military College of Canada, said.

“But that posture has to be maintained to be credible to both our potential enemies and our allies. Flying around too long in a bunch of old junk isn’t credible.”

“One of the reasons we got what we did during the Cold War was to be part of this large credible deterrent posture. But we’re watching that fail now,” – Sean Maloney, Royal Military College of Canada

Meanwhile, Russia and China, in addition to massive commitments in the Arctic in everything from industry to infrastructure, also continue to make investments in defence and weapons technologies.

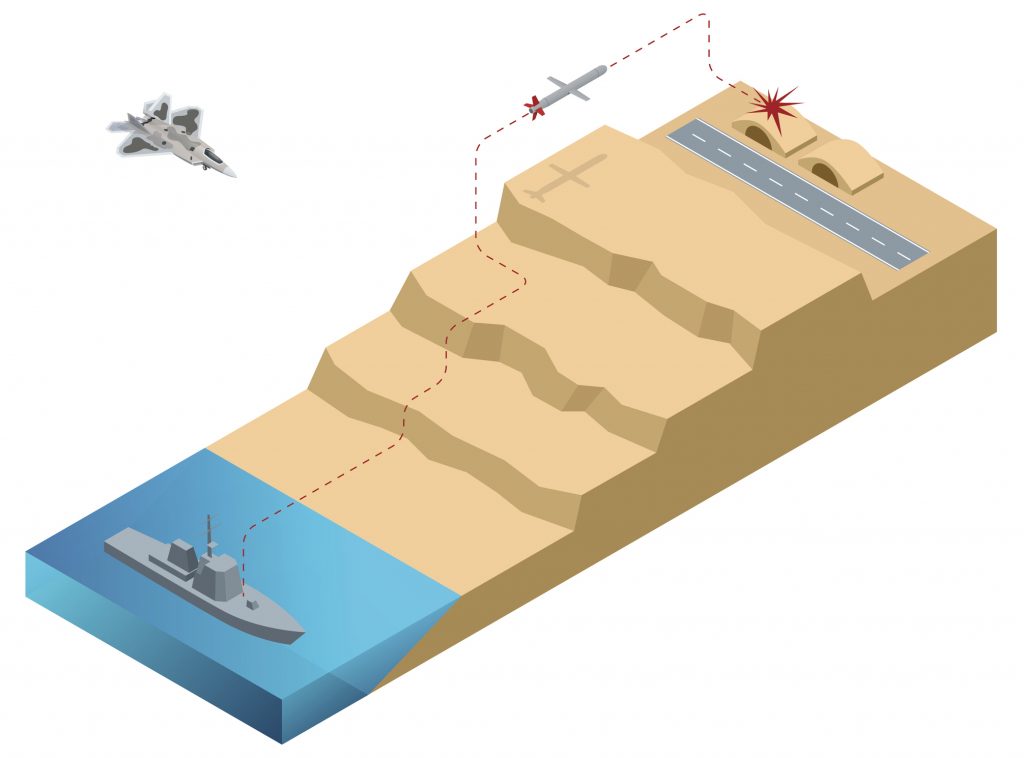

Long-range cruise missiles and hypersonic weapons developed by Russia and China are the two most pressing threats that present defence problems for NORAD.

Long-range cruise missiles fly close to the ground on a pre-programmed route and have what’s known as terrain mapping, something that vastly increases their accuracy and precision and makes them difficult to detect.

“For ground-based radar, the types we have right now in the Arctic, they pretty well, can’t see long-range cruise missiles,” said James Fergusson, a NORAD expert and deputy director of the Centre for Defence and Security Studies at the University of Manitoba.

“In the past, Russian bombers carrying cruise missiles would have had to approach, or come right into the northern Arctic territories, and we’d have time to intercept them with fighter jets before they released their cruise missiles.

“But now, with long-range cruise missiles, they can be released much earlier and higher up from the Arctic Ocean.”

Russia’s development of hypersonic weapons is another major concern.

Hypersonic weapons travel at least five times the speed of sound and can neither be detected or defended against in time.

“Hypersonics are designed primarily to defeat ballistic missile defenses,” Fergusson said. “They have sensor capabilities on them, so if something is approaching to intercept them, they can move out of the way.”

The Russian government announced it was putting the technology into production in 2018, but Canada still has no plan in place should the country ever be directly threatened by the weapons.

“Hypersonic weapons are extremely difficult to detect and counter, as such, we’re working closely with the U.S. Department of Defence in research and development work to address these challenges,” Canada’s Department of Defence said in emailed comment, pointing to Canada and the U.S.’s joint statement on NORAD modernization in 2021.

“We fully recognize that one of the most fundamental challenges facing North American security and defence is the rapid pace at which both threats and solutions continue to evolve. Strong, collaborative research and development and new approaches to leveraging Canadian and U.S. strengths in innovation are critical to enabling the objectives set out above in the years to come,” – Canada’s Department of Defence

But the Kerry-Lynne Findlay from Canada’s Opposition Conservative Party and the Shadow Minister for National Defence, says it’s unacceptable that the current Liberal government has not made more robust defence investments to keep pace with the changing geopolitical environment.

“The capabilities we do have are aged, they aren’t good enough,” Findlay said, adding that Canada’s Arctic sovereignty has to be more than a buzzword.

“We have to assert it. We have to declare it. We have to defend it. And we have to show it in terms of intelligence, capability and investments that we are a reliable partner.”

Decision superiority in the age of great power competition

“Moving forward, we need to continuously look at our ability to have domain awareness, which gives us information security information dominance and, ultimately decision superiority in a globally integrated manner, whereby what we do here within North America is linked to what’s going on within Europe, and what’s going on in the Middle East,” Major-General Kenny said.

“We no longer live in a world where we have regional conflicts that don’t impact others around the world. With great power competition that we’re seeing play out right now, it’s more important than ever that we’re integrated in this approach with our obviously closest ally NATO, as we move forward,” – Major-General Eric Kenny

What Canada’s doing right

Charron says Canada’s investment in over-the horizon radar, that can look over the curvature of the earth, is an example of where the country is doing things right.

But she says the kinds of massive investments needed for things like AI to interpret data and the kind of cloud computing needed to better share information with allies and partners remain a hard sell politically and that an increasingly partisan culture is preventing the kinds of national conversations Canadians need to have.

“We need the resources to spend on things that the public isn’t necessarily going to see and that politicians can’t point to,” Charron said.

“You spend a lot on deterrence in the hopes you never need it. We haven’t been good at having open, honest discussions with the Canadian public, but we really are at a stage in the global strategic environment where we need to be resilient,” – Andrea Charron, University of Manitoba

Looking towards the federal budget

In August of 2021, Canada’s then-minister of National Defence Harjit Sajjan, and the Secretary of Defence of the United States, Lloyd James Austin III, issued a joint statement on pursuing the modernization of NORAD “in the coming years” to better detect, deter and respond to threats or aggression against North America.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Canadian government has made a series of defence announcements, including launching negotiations to replace the country’s aging CF-18 fighter jets with the F-35, and promising significant defence spending in the April 7 budget that will include NORAD modernization and strengthening Canada’s presence in the Arctic.

And last month, Canada’s Defence Minister Anita Anand said that options she’d presented to cabinet ahead of the April 7 budget included boosting the country’s defence spending to more than two per cent of the GDP.

The NATO guideline is two per cent and Canada currently spends 1.39 per cent.

Fergusson says he hopes to see serious ongoing funding to support the kinds of technologies that need to come online for NORAD to keep pace with the world’s evolving threat environment, as well as account for the kinds of system redundancies needed to keep it secure.

“We think too much in Canada that NORAD modernization is just about the North Warning System and new fighter jets, but it’s much more and much bigger than that,” – James Fergusson, University of Manitoba

Maloney says he’d also like to see increased infrastructure investments across the North in everything from icebreakers to surveillance to make the Canadian Arctic more resilient to even things like grey zone threats.

“It’s a question of Canadian sovereignty because anything from scientific exploration to environmental operations by other countries in the Arctic proximate to Canadian territory can be a threat if it gives them information we don’t have ourselves and aren’t capable of getting ourselves because we don’t have the resources.”

Danger not of attack, but of becoming a weak link

Defence experts highlight that Canada is under no immediate military threat and that it’s important to not be alarmist when discussing the country’s security issues.

But after years of under-investment in the country’s military, sober discussion is needed to prevent Canada from becoming a vulnerability for its partners, they say.

“The first priority of all governments is to defend Canada first, North America second and then help in the rest of the world,” Charron said.

“Before we used to send the Canadian Armed Forces into the world thinking ‘this is how you protect North America.’ But Canada needs to make sure we are actually doing things to protect North America here, because we are becoming a weak link with our allies and neighbours.”

Write to Eilís Quinn at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Cet article est également disponible en français sur Regard sur l’Arctique

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Canada’s northern premiers use Arctic security concerns to press Trudeau for infrastructure investments, CBC News

Finland: Finland and Sweden to “strengthen interaction with NATO”, Radio Sweden

Greenland: Greenland, Denmark and the Faroe Islands sign terms of reference for committee on foreign affairs and defence, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Nordic countries halt all regional cooperation with Russia, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Ukrainian president warns Norway against Russian Arctic militarization, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Sweden takes part in Arctic military manoeuvres with NATO countries, Radio Sweden

United States: Radar returns to the Arctic, thrusting communities into geopolitical crosshairs, Blog by Mia Bennett