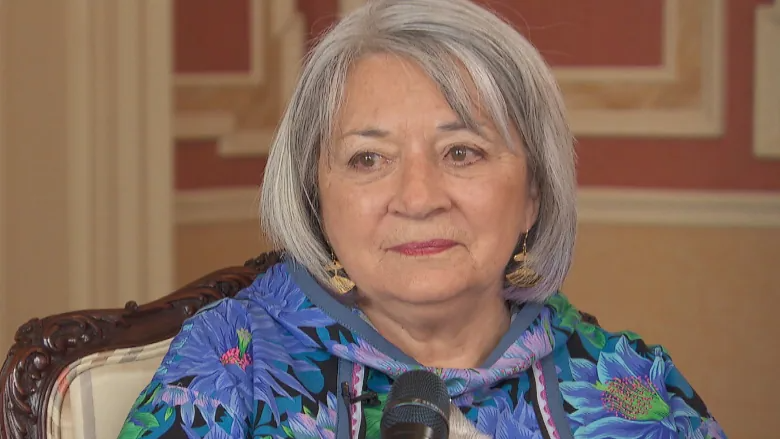

Indigenous communities ‘expecting more’ from Pope’s visit, says Canada’s Gov. Gen.

Pope expected to reiterate apology in July, but First Nations groups hope for compensation, action

WARNING: This story contains distressing details.

Indigenous communities are “expecting more” from Pope Francis when he visits Canada in July, says Gov. Gen. Mary Simon — but she said she’s uncertain if he’ll deliver.

The Pope apologized for ‘deplorable abuses’ at residential schools when Indigenous delegations visited Rome in April, but the pontiff faced criticism for denouncing the conduct of some members of the Catholic Church, rather than taking responsibility for the role of the wider institution.

There is also concern in the First Nations community that the qualified apology did not address the issue of compensation, document disclosure or the extradition and prosecution of those known to have participated in abuse.

The pontiff will visit Canada in July, and is expected to reiterate the apology on Indigenous land.

“I suspect that it’s going to be similar to what he said at the Vatican, but people are expecting more — that he will include the Church as an institution,” Simon told The Current’s Matt Galloway in an interview in Rideau Hall.

“I don’t know if that will happen or not … I’m just talking about some of the expectations that I’ve heard from some of the Indigenous leaders,” she said.

Simon was appointed Canada’s Governor General last July — the first Indigenous person to hold the position — after a decades-long career as an Inuk leader and an advocate for Indigenous rights.

In the 1970s and 1980s, she negotiated landmark agreements that saw provincial and federal governments recognize Indigenous rights. She served as ambassador for circumpolar affairs in the late 1990s, concurrently holding the position of Canada’s ambassador to Denmark from 1999 to 2001.

As Governor General, Simon said part of her role is to increase awareness of what happened to Indigenous peoples, and “to find that conversation that allows people to understand why reconciliation is needed.”

“This whole era of colonization and residential schools was not known by a lot of Canadians,” she said. “In fact, I’ve talked to many Canadians that didn’t know that there was a residential school around the hill in some of the cities.”

She sees her mandate as one that can “bring this conversation together in a way that will allow us to tell our stories, be more respectful of one another and to give space for different cultures and different languages.”

She said it’s a challenging task, but she noted that reconciliation is something that needs to happen “every day — it’s a journey, it’s the way we live.”

Apologies for historical abuses, like the one sought from the Pope, are an important part of that process, which can allow “people to heal in many ways,” she said.

“But it can’t just be words, it has to be followed with action.”

Calls for royal apology

Earlier this month, Indigenous leaders also called for Queen Elizabeth to apologize for the operation of residential schools and for the harmful effects of colonization.

Simon met with the Queen in March, but she said that conversation was about reconciliation in a more general sense.

She said her mandate as Governor General is to represent the Queen in Canada and work with Indigenous communities and Canadians — but she said that she is “not involved in political issues with this job.”

She can see where calls for an apology may be coming from, “and how it might evolve, but right now, I don’t involve myself too much in that part.”

Trudeau heckled due to community’s grief: Simon

Simon was in Kamloops, B.C., last week at a ceremony to mark one year since Tk̓emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation announced preliminary findings that indicated the remains of 215 children buried at a site adjacent to the former Kamloops Indian Residential School.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau spoke at the Kamloops event, but he was heckled by some of those present, who chanted “Canada is all Indian land,” and, “We don’t need your Constitution.”

Trudeau told the crowd he heard their concerns and that his government was committed to joining Indigenous communities on their healing journey.

Simon said the heckling was an expression of anger born out of grief, conveyed “towards the man that represents the country.”

But she said it doesn’t mean the community won’t ultimately work with Trudeau and the Canadian government — adding that Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Kukpi7 Chief Rosanne Casimir has told her that the First Nation will find ways for them to work together.

“I think we need to allow people to process that grieving,” Simon said. “Probably the next time the prime minister goes, it will be very different.”

Even though the abuses at residential schools were documented by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Simon said the evidence of unmarked graves last year seemed to wake Canadians up to what had happened.

She felt the need to go to Kamloops and support those affected by the confirmation of burial sites, from elders to younger people living with intergenerational trauma.

“It meant a great deal to me as an individual to be able to do that — and to support them in their journey to deal with these atrocities,” she said.

Creating a better country, together

Simon said she believes that Canada is moving forward on reconciliation, and she sees the conversation happening in more and more places in society.

“I was at a school yesterday in Victoria and you know, five- and six-year-olds, they were talking about reconciliation in their own way and asking me questions,” she said.

“That’s the part I love about my job, is to be talking to students.”

She wants to help people find ways to live together respectfully, with equal opportunity, and the freedom to express different cultures, languages and diversity.

“Canada is such a diverse country, it’s not just really about Indigenous peoples and Canadians, but it’s all Canadians that need to talk to each other,” she said.

“I think it’s really important for people to realize that each of us has a responsibility to create a better country, and we have to do it together.”

Support is available for anyone affected by their experience at residential schools or by the latest reports.

A national Indian Residential School Crisis Line has been set up to provide support for former students and those affected. People can access emotional and crisis referral services by calling the 24-hour national crisis line: 1-866-925-4419.

Written by Padraig Moran. Produced by Julie Crysler and Paul MacInnis.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Pope Francis to visit Arctic Canada in July, CBC News

Finland: Sami Parliament in Finland agrees more time needed for Truth and Reconciliation Commission preparation, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Sami education conference looks at how to better serve Indigenous children, Eye on the Arctic

Sweden: Sami in Sweden start work on structure of Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Eye on the Arctic

United States: Alaska reckons with missing data on murdered Indigenous women, Alaska Public Media