Levels of ‘forever chemicals’ in Antarctica are increasing says study

Fluorinated ‘forever chemicals,’ known as such because that do not naturally break down in the environment, are increasing in one of the most remote regions of Antarctica, researchers have discovered.

“We found that the longer-chain chemicals actually continued to increase in the snow throughout the 2000s and haven’t really declined at the rate that we thought they would do, while the shorter-chain chemicals have massively increased,” Crispin Halsall, the environmental chemist at Lancaster University who led the study, said in a phone interview.

Among their findings, the shorter chain compound, perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA), was shown to have increased significantly from 2000 to 2017.

The term ‘forever chemicals’ refers to per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS), a group of more than 4,700 manufactured chemicals used in a variety of industries and consumer products ranging from fire-fighting foam and lubricants, to non-stick coatings for pans and water-repellent for clothing.

Although only a portion of PFAS have been extensively studied, the ones that have, like PFOS, PFOA, and long-chain PFCAs, have been observed to have negative environmental and health impacts.

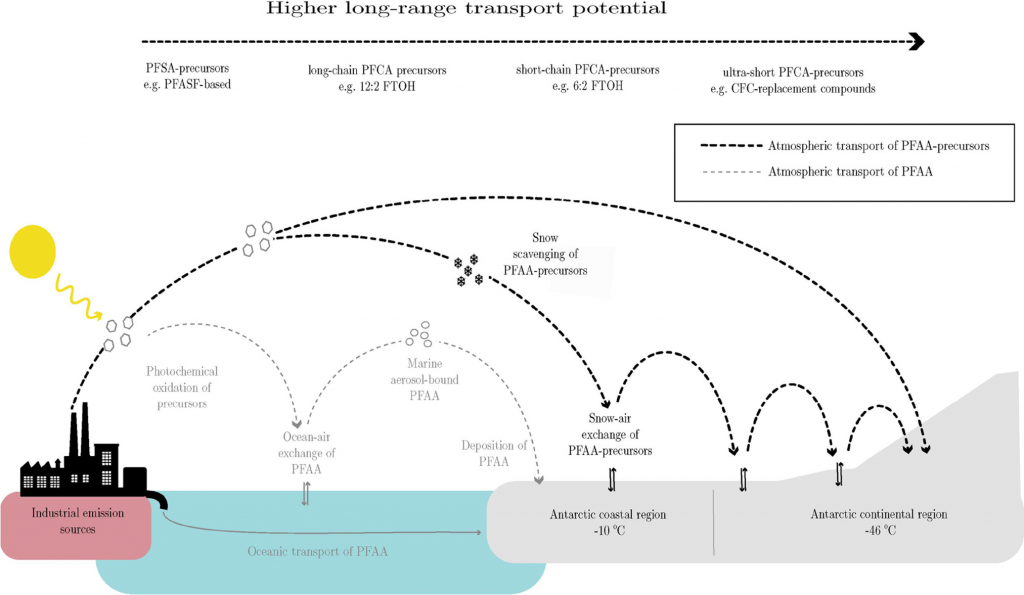

The use of short-chain PFAS replacements for CFCs, phased out following the 1987 Montreal Protocol because of their harm to the ozone layer, could be responsible for the short-chain increases noted by the recently published study in the journal Environmental Science & Technology.

“Around the turn of this century and onwards, industry started to phase out the long-chain PFCAs and started switching to short-chain carboxylic acids on the premise that the longer-chain chemicals actually do bioaccumulate and shorter-chain chemicals don’t and so they could still produce the substances that they wanted but with the shorter-chain compounds,” Halsall said.

“We really wanted to look at whether the background atmosphere reflects what’s been happening with industry over the last few decades.”

‘Getting the global background signal’

To do the study, researchers from Lancaster University in the U.K., the British Antarctic Survey and the Hereon Institute of Coastal Environmental Chemistry in Germany, cut and examined cores at the Dronning Maud Land plateau in eastern Antarctica, over 2,000 metres above sea level.

The area is one of the highest and remotest places on the continent was chosen expressly for that reason, Halsall said.

“For this particular study we wanted to get away from the coastal margins and be up in the troposphere to get that really global background signal,” he said.

“The important feature for us was that it’s quite an elevated site, so you’re sitting on a lot of accumulated ice and that’s great for our purposes.”

At the site, researchers cut snow cores 10-metres long, allowing them to chart the chemical build up over decades.

“We really wanted to establish a long-term deposition record in Antarctica just to build up that time series of chemical contamination in the snow, starting with a time that predated the modern fluorine industry,” Halsall said.

“The deepest part of the snow core went back to the early 1950s and predated the fluoropolymer industry.”

Arctic, Antarctic parallels

The findings in the Antarctic also mirrors research done on Devon Island in Arctic Canada.

The island is extremely remote and has no permanent residents, but researchers sampling ice cores there, also detected high levels of CFC-replacements.

“They were able to detect more chemicals then we could, simply because our site is so remote there’s only a small handful of chemicals that manage to make it,” Halsall said.

“But the trends do follow what has been observed in the Canadian Arctic. Although at our site, we are still seeing relatively high levels in recent years of the long-chain acids, whereas in the Canadian Arctic, the levels of those long-chain compounds in snow and ice are starting decline now.”

Time to consider total PFAS ban?

Crispen said given the known adverse effects of forever chemicals observed in health and the environment, and the accumulated findings in recent studies, it may be time to think of banning PFAS entirely.

“There is a lot of concern just about the sheer quantity of these chemicals in the environment at the moment, in temperate regions and not just remote environments, and whether international legislation and various environmental agencies are looking to ban the entire group of these chemicals and not just individual compounds, ” he said.

“I think the evidence that we’re providing gives support to banning the whole group of these chemicals because it’s just not sustainable.”

Write to Eilís Quinn at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: ‘Significant’ amounts of mercury in permafrost threatens Arctic food supply, research says, CBC News

Finland: Citizens’ initiative prompts Finnish lawmakers to consider microplastics ban, Yle News

Greenland: Greenland accedes to UN treaty against mercury pollution, Eye on the Arctic

Sweden: Swedish raft made from trash draws attention to plastic pollution, Radio Sweden

United States: Keep Yukon ore out of Haines, Alaska, conservationists say, CBC News