Blog: Earth’s temperature rises as geopolitical climate cools

It’s now one year since Russia invaded Ukraine. There’s no sign of any end to the conflict. And we are not looking at a regional dispute. This war has become a major clash between systems, with repercussions for the whole planet.

Putin’s invasion has plunged us into a time of multiple crises – war, an economic downturn, threats to energy and food security…. Oh and wasn’t there something else? Ah – Climate change. It seems to have faded into the background of media world affairs coverage. Yet it cannot be separated from the other crises dominating the headlines; on the contrary – it both influences and is influenced by the other things happening in the world around us.

In three weeks, the IPCC Sixth Assessment Synthesis Report will be released. It will bring together science on impacts, adaptation and vulnerability, and mitigation of climate change. There will be no surprises. CO2 emissions are at their highest ever. We know what to do – cut emissions, protect nature, help people, build resilience. But…

Data jigsaw

I returned from the recent Arctic Frontiers meeting in Tromsø, Norway’s Arctic capital, with a heightened sense of concern about how Russia’s war on Ukraine is affecting the Arctic – and efforts to protect the global climate. The experts gathered there outlined how this latest cold war is hampering data collection and research collaboration which are essential to keep track of how our climate is changing and what action we need to adapt to that and to put the brakes on it.

As the President of the University of the Arctic (UArctic) Lars Kullerud put it – “we need the data to save the world”. The university network has 55 Russian institutions amongst its membership. They have had to be excluded following the invasion of Ukraine. We have never been as detached from Russian scientists, says Kullerud – even in the Cold War years.

Without access to Russian scientists and territory, scientific data on the Arctic is incomplete. Given the huge expanse of Russian territory in the high north, the gap is enormous. Scientists have to rely on space-based data to try to track what is happening in the Russian Arctic.

Joint research programmes and university courses between institutions in western Europe and Russian Universities have been put on hold. “Permafrost and boreal forest cannot be solved without Russia”, is Kullerud’s sobering reminder. He fears contacts could be lost for ten years or more. If it takes that long, he says, we have to start from scratch – and under much harder conditions.

Final day of @arcticfrontiers. Interesting discussion on Arctic science. pic.twitter.com/ir0zFzfz4i

— Petteri Vuorimäki (@PVuorimaki) February 2, 2023

Finland’s Arctic ambassador Petteri Vuorimäki – reminisced in Tromsø about how back in 2021 he had been full of optimism about the upcoming 2-year Russian chairmanship of the Arctic Council. He was looking to major progress on major issues like black carbon and methane. Instead, the invasion of Ukraine in 2022 brought cooperation between Russia and the other members of the Arctic Council to a standstill. When Norway takes over the Chair this month, it will be a council of seven, with the major player Russia on the outside.

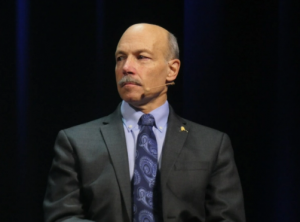

Mike Sfraga, Chair of the US Arctic Research Council was a key figure at the Tromsø meeting. Shortly afterwards, he was nominated for the newly created post of US Ambassador-at-Large for Arctic Affairs. With the isolation of Russia, he spoke of “mourning a loss” in the science community. The “single, large, existential threat is climate change – now global heating”, Sfraga told a session on the future of Arctic science and “science diplomacy”. He likened the situation to putting together a puzzle, with only fifty percent of the pieces. There have often been challenges in the past, Sfraga admits. But right now, “the doors are very much closed.”

Setbacks for science

The US expert spoke of experiencing an “emotional high” from the MOSAIC expedition, an “ideal international collaboration”. Now, he says “humanity’s darker sides”, with the “brutal war in Europe”, are impeding efforts to tackle the existential threat involving the whole planet.

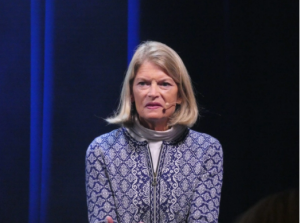

Nicole Biebow, from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) and Chair of the European Polar Board says that landmark MOSAIC expedition to research climate change in the Arctic would never have been possible under the current conditions. Russian support was essential. Now, long-term cooperation built on trust and mutual understanding has been completely shut down, she said.

The western response to how science should deal with the war-induced rift with Russia is not the same everywhere, scientists report. Some, including UArctic President Kullerud, are critical of restrictions on communication with Russian colleagues imposed by some western countries as part of the sanctions package. Freedom of speech and of science have also become victims of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, he said, and stressed the need to maintain person-to-person links in spite of the difficulties and dangers.

Could the lack of data mean we could miss a climate tipping point? That crucial question was put to the panel of experts. Yes, was the worrying answer. And, Kullerud pointed out, we will also miss out on solutions.

Given the short window we have to keep temperature rise below 2°C, we really have no time for this.

The Arctic this winter

It has been an exceptional winter in many parts of the Arctic, which is warming around four times faster than the global average. In some areas, the rate is even higher. Jon Aars is a Senior Scientist at the Norwegian Polar Institute in Tromsø, studying polar bears, who are dependent on sea ice to hunt the seals, their main food source. With tracking collars attached to their necks, each bear transmits a daily position via satellite. In an interview to mark International Polar Bear Day on February 27th, Aars told Thomas Nilsen of the International Barents Observer there was no reason to celebrate at the Arctic archipelago Svalbard.

“This is a very special winter compared to what we had 20 years ago. If someone twenty years ago said that all northern coast of Svalbard would be ice-free mid-winter in 2023, nobody would believe it,” Jon Aars told the publication.

“That said, if we compare what we see today with the last 7-8 years, it’s becoming the new normal. Maybe five of the latest years have been like this with no ice around some of the islands.”

Maps provided by the ice service of the Norwegian Meteorological Institute paint a grim picture. There is close to no sea ice around the southern, western and northern coast of Spitsbergen, the largest island in the Svalbard archipelago.

“The Barents Sea population of polar bears has lost two months of sea ice since I started to work,” Aars told Nilsen. The Polar Institute started annual monitoring of polar bears’ movements in 1987.

According to the National Snow & Ice Data Centre (NSIDC) with the University of Colorado Boulder, Arctic sea ice rose at a slower-than-average rate through January and reached the second-lowest extent in the satellite record by the end of the month, the Barents Observer reports. Least ice compared with normal was found around Svalbard, as well as west and south of Novaya Zemlya in the Barents Sea.

The lack of sea ice in the Barents Sea likely also contributed to above-average air temperatures, according to NSDIC. January 2023 was the warmest ever in modern times in Norway’s northernmost region, Finnmark.

Several record heat waves are currently sweeping Asia:

Monthly heat records are being broken from the European Russia (tweet later) to Saudi Arabia to India (38.8C at Mangalore Panambur) to Myanmar (34.7C at Gwa) to China (5 records in 2 days) and Siberia.

And it'll get hotter. pic.twitter.com/2Nz58rmdj2— Extreme Temperatures Around The World (@extremetemps) February 27, 2023

Geopolitics – hotting up with the climate

Against the background of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the warming Arctic has taken on increased geopolitical significance. The Norwegian Institute of International Affairs and the US Wilson Center delivered a special report to the Munich Security Conference last month: Navigating Breakup: Security realities of freezing politics and thawing landscapes in the Arctic” .

“Long gone are the days where the Arctic could be treated as something exceptional as a region which is insulated from the issues and politics of the rest of the world. On the contrary, in a time where climate change is heating up the region quite literally, territorial conflicts and access to resources like oil and gas are simmering underneath the ice floes, too”, writes Bendikt Franke, Vice-Chairman and CEO of the Munich Security Conference, in the Foreword. Climate change in the Arctic, he confirms, has considerable security and geopolitical implications.”

The stand-off between Russia and the western allies supporting Ukraine is a dispute between close neighbours in the Arctic region.

“We are 57 miles apart from mainland to mainland, some islands in the middle separated by water of a few miles. So we’re paying very close attention to Russia, as we always have”, Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski told a press conference in Tromsø.

“There has been an engagement coming out of the United States that I think is as impressive and aggressive as certainly I have seen since I began my engagement on Arctic issues some 20 years ago”, she added

The Norwegian Foreign Minister Anniken Huitfeld stressed the need to avoid conflict with the country’s aggressive neighbour, in spite of the diminished cooperation caused by the Ukraine war. With Sweden and Finland striving to join NATO, the Arctic unavoidably becomes a frontier region between factions on both sides of the Ukraine divide.

Geopolitical tensions in the Arctic are not new. As climate change made the Arctic more accessible to shipping and exploration for the oil and gas reserves slumbering under the ice, Arctic and non-Arctic nationals including China have been keen to claim a share. Now, the “green energy transition”, with its need for rare earths, minerals and metals, has increased the hunger for potentially even more lucrative resources.

All this does not bode well for peaceful cooperation and resource-sharing in the Arctic region.

Out of the frying pan…?

Olivia Lazard, a Fellow at Carnegie Europe, warned in a keynote in Tromsø against replacing the rush for fossil fuels by a new rush for minerals and other resources, destroying the planet in a different way. Europe could be walking from fossil dependency to another, she said. And the race for these new resources could endanger planetary health, democracy and peace.

The Arctic, she stresses, sits right in the middle as a key area in this global competition. And we all find ourselves in a “systems rivalry of planetary importance”. We can’t do business as usual. We must develop a system – including no-mine zones – to make sure the energy transition does not undermine vital eco-services, Lazard argues. We have to look at the climate crisis in conjunction with other environmental crises. “We can’t plunder the planet on our way to saving the climate!!”

“Nothing about us without us”

Struggling to be heard in the debates over natural resources are the indigenous communities who live in the Arctic: the Aleut and Yupik (United States); the Inuit (Canada, Greenland and the United States); the Chukchi, Evenk, Khanty, Nenets and Sakha (Russia); and the Saami (Finland, Norway, Russia and Sweden). These communities are represented by six organisations on the Arctic Council — the Aleut International Association, the Arctic Athabaskan Council, the Gwich’in Council, the Inuit Circumpolar Council, the Russian Association of Indigenous People of the North and the Saami Council. But with the disruption of the Arctic Council through the Ukraine invasion, and connections between groups in Russia and elsewhere made difficult to at times impossible, it has become more difficult for them to make their voices heard on matters affecting their homelands.

Many of the resources so hotly pursued for the energy transition are on those lands. Wind turbines interfering with reindeer pastures are just one of the conflicts attracting media attention, like the current dispute in Norway.

In October 2021, Norway’s Supreme Court ruled that the construction of certain wind turbines violated the rights of the Sami, who have been using the land to raise reindeer for centuries. However, the wind farm is still operating. The protesters from organizations called Young Friends of The Earth Norway and the Norwegian Sami Association’s youth council NSR-Nuorat, recently staged protests which forced an apology from the Norwegian government.

Environmental campaigner Greta Thunberg and dozens of other activists blocked entrances to Norway's energy ministry, protesting against wind turbines built on land traditionally used by indigenous Sami reindeer herders https://t.co/tOavSlScib pic.twitter.com/Zp7JDEyzaM

— Reuters (@Reuters) February 27, 2023

Glass half-empty or half-full?

The world’s CO2 emissions are at a record high.

📈 419.94 ppm #CO2 in the air at Maunakea for the 8th week of 2023 📈 Up from 419.53 a year ago📈 @NOAA Mauna Loa data via 'MKO': https://t.co/CkSjvjkBfQ 📈🌎 https://t.co/DpFGQoYEwb links: https://t.co/idlRE62qB1 & https://t.co/ZezSmdYUVo & https://t.co/NnwgaBoCCa 🌎 pic.twitter.com/ONB9YFLBWa

— CO2_Earth (@CO2_earth) February 27, 2023

But they didn’t rise by as much as experts feared:

The global energy crisis fueled fears of runaway growth in the world’s CO2 emissions – but new @IEA analysis shows emissions rose by less than 1% in 2022 as a surge in clean energy offset most of the increase in emissions from coal & oil

Find out more ➡️ https://t.co/cAir97TVpJ pic.twitter.com/S8xv4Cgur1

— Fatih Birol (@fbirol) March 2, 2023

The latest figures from the IEA can be interpreted in different ways, depending on your viewpoint:

Renewables will be world’s top electricity source within three years, @IEA data reveals | @DrSimEvans

Read: https://t.co/JzgGZaOdXX pic.twitter.com/yz6qexEB14

— Carbon Brief (@CarbonBrief) March 2, 2023

There are signs of hope – but only if we can drastically up the tempo of emissions reductions.

Time to reform the UN climate process

Amongst the climate stories you might have missed because the media is occupied with other things, is a new initiative by the Club of Rome:

Club of Rome calls for radical reform of #UNFCCC #COP – smaller, more frequent meetings, regular science updates, bringing non-state actors into the formal negotiations, more accountability https://t.co/pZFQP5inpe

— Wolfgang Obergassel (@obergassel) March 1, 2023

A group of experts, scientists and policy leaders — including Laurence Tubiana, former Climate Change Ambassador for France and CEO of the European Climate Foundation, Mary Robinson, former President of Ireland and UN Special Envoy on Climate Change, and Ban Ki-moon, former Secretary General of the United Nations — have signed a letter calling on the Secretary General of the UN António Guterres and Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC Simon Stiell to reform the COP process to ensure it can deliver results:

“With all essential components of the global climate agreement now finalised post-COP27, the United Nations needs to shift gear and focus all efforts on the delivery of global goals and commitments in the lead-up to 2050. Successful delivery requires an urgent reform of the COP process. We, the undersigned, are committed to creating a sustainable, healthy, just and equitable Earth for All and we stand ready to support the United Nations in future-proofing the COP summits to close the gap between science and action, preventing current crises delaying progress and enabling the safe landing of global climate commitments.”

The signatories say all the essential legally binding documents and guiding declarations committing the world to holding global warming below 2°C and aiming for 1.5°C are in place. Yet it has taken 7 years since the 2015 signing of the Paris Agreement to finalise all its components including carbon trading and loss and damage funding.

The current COP and Presidency leadership process cannot deliver climate action at the speed required to avoid the worse impacts of global warming and create a more equal, cleaner world for all.

“The Paris Agreement is central to tackling the climate crisis, but its annual summits can’t continue with business as usual. The gap between targets and real emissions is dangerously wide. We need to inject new purpose and momentum into the COP system or it will lose its relevance at the most critical time.” says Tubiana.

Mary Robinson reiterates the deep disappointment expressed by signatories that “COP27 Parties could not even reach consensus on phasing out fossil fuels”. This consensus will never be reached if fossil energy interests are prioritised over the “Paris Agreement goals.”

“The COP process remains, from a climate action perspective, completely disconnected from scientific necessity,” says Johan Rockström, Director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research:

“While this process inches forward with new targets and pledges, global emissions and temperatures continue to rise, and climate extremes occur more frequently and with more severity than expected. This lethargic progress is totally at odds with climate science and real-world climate damage and risks.”

Turning up the pressure

Friday March 3rd saw the latest global Fridays for Future climate strike. The younger generation is getting increasingly frustrated. Here in Germany, there was an added factor this time: public transport strikes organised by the powerful trade union Verdi. A lot of people like myself will have been irritated that there was no public transport to get to the demonstration venue. For some people, it’s just too far to walk or cycle. But this could be the start of an interesting trend. If trade unions and other movements get behind the climate cause, the pressure on government to speed up climate action will increase.

Remember the "Climate Spiral"? This popular @NASAViz visualization now runs up to 2022 and is available in both degrees Fahrenheit and Celsius. Learn more and download the video here: https://t.co/2iRaWWzu0q pic.twitter.com/8R7auJNpgu

— NASA Climate (@NASAClimate) February 28, 2023

All in all, as spring starts in the northern hemisphere, I would love to opt for the optimistic interpretation of the latest IEA emissions figures and progress towards zero emissions. But as yet another top-level meeting of the G20 nations ends without a joint statement, with Russia continuing to insist the West is to blame for everything, and China refusing to condemn the Russian invasion; with rumours that China is seeking new ways to provide its fellow authoritarian state with weapons; with a conflict escalating that is both in itself increasing emissions and taking the eye off the climate action ball – I would have to close my eyes and ears to be confident we are on the path to attaining those climate targets to halt global heating in time to avoid the worst.

Still, I live in hope.

Related stories from around the North:

Arctic: Blog: Moving North – Arctic Frontiers in a changing world, The Ice Blog

Canada: Ties in North American Arctic stronger than ever, says Canada, Eye on the Arctic

United States: A year after Russia invaded Ukraine, a walrus discovery is caught up in geopolitics, Alaska Public Media