Blog: Greenland’s Roles in Arctic Security: Many Paths Leading to One?

Earlier this month, after the last political obstacle to Sweden’s admission to the alliance, specifically previous opposition from the Hungarian government of Viktor Orbán, was removed, Sweden became the thirty-second member of NATO, further moving the country away from what used to be a staunch tradition of neutrality which lasted well over a century. Military cooperation between Norway and the United States has also deepened in recent years, as Oslo announced plans for significant increases in its defence budget.

Across the Atlantic, the US Department of Defence is preparing an updated Arctic strategy for release later this year, and questions persist over to what degree Russia and China may deepen their level of regional cooperation, based partially on mutual opposition to NATO’s expanded Arctic interests. The Arctic Council, under the chairship of Norway, is seeking ways of improving cooperation under these conditions, further complicated by the decision by Moscow announced that month to suspend [in Russian] its annual payments to the group until the Russian government sees that normal dialogues involving all members can resume.

Very much in the centre of these Atlantic-Arctic events is Greenland, which has found itself at the centre of much attention because of its perpetual ‘canary in the coalmine’ status for those measuring the effects of climate change and ice loss in the far north, but also because of its strategic location and its mineral wealth, which includes ‘strategic materials’ essential for high technologies and environmental applications.

Many major economies are now actively looking for alternative sources of these materials, including rare earth elements, and much of this market continues to be dominated by China, (another Arctic government, Norway, had passed controversial legislation in January this year which would allow for seabed mining of precious metals used in green technologies, despite loud opposition from environmental interests). Nuuk is now finding itself at the centre of the critical resources debate in many countries as governments seek various green transition solutions.

Greenland is part of the Kingdom of Denmark, but since the island ceased to be a Danish colony as of 1953, governmental powers have been in the process of being transferred to Nuuk. The ‘Act on Greenland Self-Government’ (Self-Rule Act) of 2009 granted Greenland further autonomy, as well as the right to self-determination including the option for eventual independence. However, Denmark retains jurisdiction of both Greenlandic defence and foreign policy, but that has not meant that the island has been a passive foreign policy actor. Various initiatives [pdf], including the 2003 Ittileq Declaration [in Danish] which gave the Greenland government equal status [pdf] to that of Copenhagen in issues regarding the then-American Air Force Base at Thule (now Pituffik).

The following year, the American and Danish governments, signed an agreement [pdf] in Igaluku, Greenland which acknowledged ‘Greenland’s contribution to the mutual security interests and its consequent sharing of the associated risks and responsibilities’ in areas regarding regional security, and allowed for extensive participation of the Greenland government in matters surrounding the American military presence on the island.

With the official opening of Greenland’s representative office in Beijing in October 2023, the island now has five such facilities, with the others being in Brussels, Copenhagen, Reykjavík and Washington. The United States and Iceland also have Consulates-General in Nuuk, and this month the European Office in the Greenlandic capital was opened with two new financial agreements in the areas of education and energy cooperation, with the latter deal covering green innovations such as hydrogen, as well as environmental protection and effective use of strategic materials.

Danish, Greenlandic and English versions of the report can be downloaded here, (‘21.02.2024 Grønlands udenrigs-, sikkerheds- og forsvarspolitiske Strategi for 2024-2033’)

The paper was the first of its kind to be published since 2011, and reflected [in Danish] the far more complicated security milieu Nuuk is now finding itself in. The plan was supported [in Danish] by four of the five parties currently holding seats in the Greenlandic parliament, or Inatsisartut, including the two largest parties Inuit Ataqatigiit and Siumut, (the populist party Naleraq was the lone holdout).

The need for Greenland to be at the centre of decisions regarding the island’s foreign policy and security concerns was very much a recurring theme in the document, as well as the desire of the Greenlandic government to achieve independence and play a more robust role in international discourses both within the Arctic and beyond. The paper stressed the need to improve Greenland’s connectivity, especially with neighbours like Canada, Iceland, and the United States, but also with essential markets in East Asia, including China, suggesting that the island was seeking a shift to a more non-aligned approach to foreign relations, especially trade issues.

In the wake of the 2019 debacle created when the US government under Donald Trump sought to purchase Greenland, the response from Greenland authorities was that the island was not for sale, but it was open for business. This has meant that Nuuk is seeking a myriad of different trade partners within the Arctic and beyond.

The document notes the more difficult strategic atmosphere in the Arctic, and the growing presence of non-traditional security threats, including attacks on economic targets and infrastructure, as well as cyberattacks. Nuuk is seeking to respond to the developments with various initiatives such as the improvement of search and rescue capabilities, a local coast guard, and further protections of domestic actors and external supply chains.

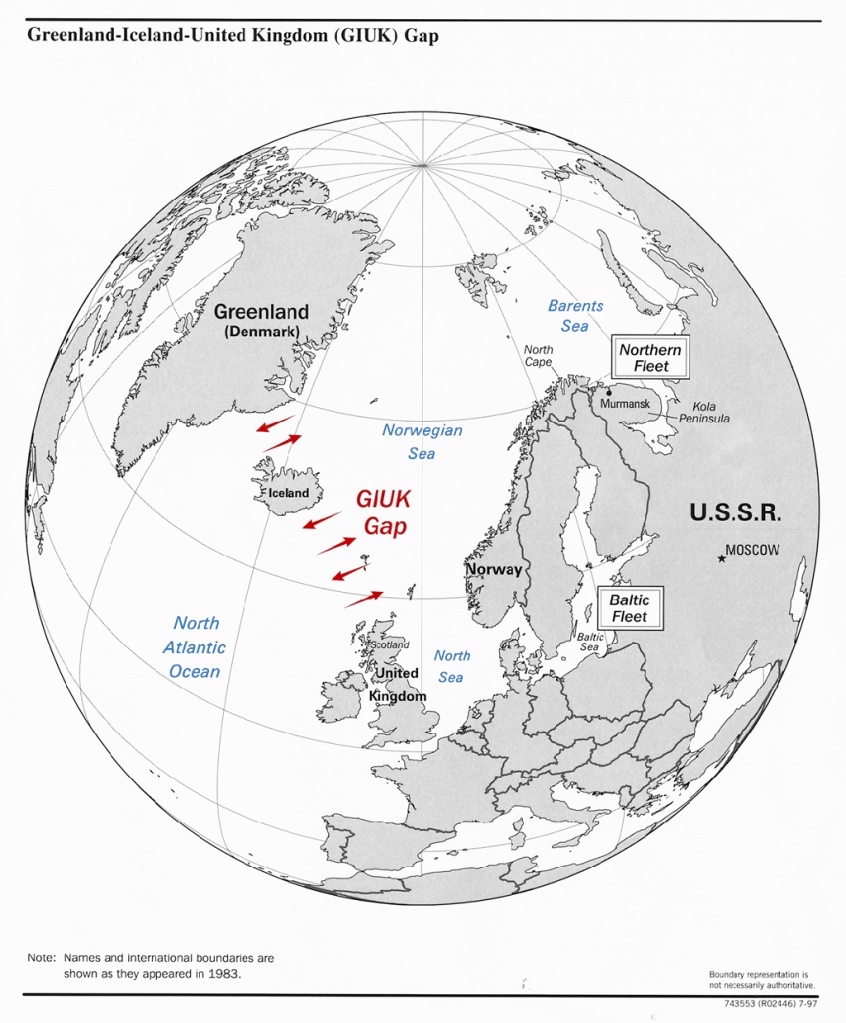

Russia was only briefly mentioned in the document, including the decision by Nuuk to join in the European Union sanctions regime against Moscow after the full Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. With the Arctic now much more central to NATO interests, and renewed concerns about the vulnerability of Atlantic-Arctic maritime routes, (such as the GIUK Gap and the adjacent Bear Gap), there will be further discussions as to what roles Greenland can play in regional maritime security.

A 1983 CIA map of the GIUK Gap and surrounding regions [Image via Wikipedia]Greenland is seeking expanded economic cooperation with North America, and has encouraged the Canadian government to follow the lead of the US also set up a consulate in Nuuk, while plans have been put into motion to establish a Greenlandic representative office in Ottawa. Canada-Greenland relations were given a considerable boost after the resolution [pdf] of the longstanding dispute over the status of Hans Island / Tartupaluk in 2022. The paper also called for a deepening of Greenland-Iceland relations, building on the bilateral agreement struck in 2021, in the seafood sector and improved communications, transportation and tourism.

In addition to bilateral diplomacy, the document noted that Greenland can contribute further to the Arctic Council as well as subregional bodies as the Nordic Council as well as the United Nations, with plans announced to set up Greenland office at the UN in New York and Geneva.

Another institution of central importance is the Arctic Council, especially given that the Kingdom of Denmark is scheduled to receive the chair in May next year, with much [in Danish] debate over the degree to which Greenland should and would take the lead [in Danish] as the Kingdom develops its Council policies for its chairship. The Greenlandic government is also supporting a new regional organisation to better connect the island with its Western neighbours.

A proposed Arctic North American Forum would link Greenland with the state of Alaska along with the Northwest Territories, Nunavik, Nunavut and Yukon, all territories which make up the greater region of Inuit Nunangat, in Canada. It was explained that all these subregions face considerable obstacles in the form of underdevelopment, social and health challenges, and brain drain situations, so there is the question of how such the group could bring more localised solutions to these problems.

Container from Chinese firm Cosco in Nuuk [Photo by Marc Lanteigne]Despite ongoing concerns in both the United States in Europe about China’s economic interests in the Arctic, the policy document stressed the need for Greenland to further deepen trade relations with Beijing, as well as with other major Asian economies like Japan, India, South Korea, and ASEAN. Greenland has been seeking to widen its array of partners for seafood exports, as well as looking to Asian markets for the expansion of tourism.

The policy document did not mention the thorny issue of mining in relation to foreign investment, a sector which Chinese firms had previously been interested in co-developing on the island. As well, Japan was cited as a potential partner for peace research, (although this at a time when Tokyo has been pursuing a more robust defence strategy, including military budget increases, in light of the changed security situation in the Asia-Pacific and closer defence relations with the US and NATO).

Greenland’s strategic paper has brought together the many different strands of the island’s foreign policy interests, and will serve as a platform for future initiatives. Nuuk is facing a serious of upcoming acid tests for its foreign relations however, including the transfer of the Arctic Council chair from Norway to Denmark next May, the growing NATO presence in the far north, and potentially the aftereffects of revised American Arctic policies and the elections in November. In keeping with the title of the document, Greenland wants greater inclusion in the deliberations surrounding changed circumstances in the Arctic, as well as a stronger voice in regional strategic affairs.

Related stories around the North: